Marsha Recknagel.

Between Two Storms.

My father’s aunt was named Inez. We had gone to see her over a Thanksgiving, the holiday that my parents spent in New Orleans at the horse races. My brother and I were left to roam the Monteleone Hotel under the loose supervision of the red-coated, epaulet-wearing doormen, an adventure we anticipated for weeks before our trip. But on the drive south from our home in Shreveport, which is in the farthest northwest corner of Louisiana, my mother said that before they went to the track we were going to see Aunt Inez. “Before it’s too late,” she said.

Inez was news to me, much less the idea that I might miss her completely. Mainly we’d visited Pappy, my father’s father, who’d moved to Victoria,Texas in the thirties, when my father was a teenager. Pappy’d worked the New Orleans-to-Victoria railroad line for twenty years. Inez was Pappy’s sister.

Inez lived on Elysian Fields and only later did I learn the avenue was famous for the Tennessee Williams’ play, and even later — while studying for my Ph.D. in literature — I learned that almost every street in New Orleans had a literary history.

We entered Inez’s dark bungalow and I smelled the coffee. My father loved coffee that tasted burned and looked like black sludge. I’d always thought the love of bitter and black was unique to him. That day I learned it was what his people drank, the way they took their coffee in his birthplace, his city of origin, New Orleans.

Riding to the hotel after the visit with Inez, who hadn’t looked ill to me, my mother complained about the coffee, said when she’d first met all Daddy’s relatives they’d expected her to drink that bitter coffee along with them, that black, black coffee that sat on the stovetop all day and night. My mother was from Austin, Texas. I’d always hated her coffee. It was brown.

They’d expected her to drink beer with them, too. “Coffee and beer,” my mother said. “Coffee and beer, coffee and beer. Never a glass of iced tea to be had in that household.” She pursed her lips and shook her head, looking out the window as my father drove, his large hand clasped around a Jax beer can.

And give them a bridge, mother would tell me, and they’ll stand there all day in their waders, with their nets and poles. My grandmother, whom I never met, died an early death because she wouldn’t quit fishing, according to my mother, who said my grandmother’s heart, enlarged from rheumatic fever, “gave out” when she went against doctor’s orders, standing waist-high in the Gulf and fishing until, mother said, she “up and died.”

My father loved to catch any creatures from the sea, but especially crustaceans, crabs and shrimp. Mother complained about the smell of boiling shrimp. She complained about the clean-up, the husks of shellfish that could infuse a house with a smell so fierce she would run around collecting the plates and scrubbing down our hands, finger by finger with a cut lemon, almost before we’d swallowed the white tender spicy meat. This world was not for her.

But it was for me.

Aunt Inez was nut-brown, long, lean, and not eager to please but not unkind. She was the first person I’d met up until then who truly was completely just who she was. Not a mother or a sister or a teacher. She was Inez. She talked the same to old and young. She looked me right in the eyes and said, “Would you like a bit of beer in your cup?” I looked into her huge mahogany eyes. Only my father offered me sips of beer.

That afternoon my Aunt Inez spoke of Grandma Recknagel, who, she told us, drank beer in the afternoons, played the horses, owned a parrot that accompanied her to casinos, and carried a small ax in a beaded evening bag to protect her and her winnings from thieves in the Quarter when she returned from the day at the track or the night at the casino.

Inez’s grandmother won and won and won until she lost everything, Inez said.

My mother, it was clear, didn’t approve of such talk. She sat in the monstrous easy chair and watched as Inez smoked a cigar, took sips of black coffee, and swapped tales with my father, her nephew. I saw parts of my father’s face in Inez’s face, the stained brown circles beneath her eyes, the long fingers, knuckled and bold, not meant to display jewels but to roll dice, shoot craps, shuffle through cards. Or hold fishing poles, bait lines.

To speak of Inez, the teller of tales, is to speak of what New Orleans meant to me. Now, four months after Hurricane Katrina, I stumble at the verb tense — means, meant. Faulkner wrote that the past is never past, that it is always present. Nostalgia is so peculiar to the South, and to my manner of speaking and thinking, that a former boyfriend who is a writer from Boston once said I reminisced nostalgically about the hour past. “Oh how fondly I recall the hour ago,” he’d mimic with a swoony voice and a hand to his forehead.

It will be years before I realize my father had brought New Orleans to me, me to New Orleans. I smoked my first joint in the Crescent City, where I also got my first “salon” haircut, lost my virginity, had my first ménage a trois. Not all in the same year, but spread out across the years like Christmas tree lights, like the ones in the small bar on Bourbon and St. Ann’s where I first heard a man play the sax so beautifully that I already started missing it before he had finished.

It was the city in which I made love with a black man for the first time, the place where the landscape of my body merged, black on white, white on black. We made love in the Bienville Hotel, on the third floor, in a room with a balcony that looked out onto a courtyard a few blocks from where he had played the sax five nights a week for twenty-one years. I first heard him play when I was visiting from Houston, where I’d moved after graduating from Louisiana State University. Time after time I’d go to New Orleans, to the 544 Club, where I watched the bead of sweat glisten on his forehead as he made the sax squeal, bringing the room to its feet, the tourists to a frenzy. Not until I was forty-five did I stay at the club until he’d finished playing. Later he would write a song about the times he’d look around and I’d be gone, over and over again, disappearing: “Sneakin’ and peekin’,” not “stayin’, not sayin’ what you been thinkin’.” The song was written after he’d read my memoir, in which he appeared, singing, playing the sax.

In the fall of 1987, another November in New Orleans, I gave a paper at a literary conference. A group of doctoral students gathered in the lobby of a hotel on Canal and wondered where to go for music. I led them — the men in corduroy jackets, denim shirts, the women in white blouses, blue blazers with artsy brooches — to the 544 Club. That night Gary stepped off the stage and played the sax before one woman then another, moving around the tiny tables covered with sticky spills, wadded up napkins, empty longnecks, whisky glasses glowing soft amber. Our group was in the far corner of the crowded bar, under the window that had the bars of an old western jailhouse. From outside the club shoeshine and break-dancing boys hung their arms through the bars and bobbed their heads to the music.

When it came my turn to be serenaded, Gary nodded his head and horn in recognition before he began to blow the shiny gold horn, swaying it up to the ceiling, his brows coming together with the effort before he brought the horn down low between his knees, almost between my legs. His eyes were wide, watching me watching him, and there was no sound, just all imagination as he stood before me and played air sax, the ghost of a tune, silent. The quietness of the club erupted into raucous clapping when he moved away, leaving me beside myself in that down and dirty club.

Years and years later, the hair on his chest gray, the saxophone player came to my home because his was gone. He came to my home in Houston, his suitcase in his hand, his horn in its case, his music in his head.

When I was in the fourth grade, my class took a train trip to New Orleans and back, with a stop in Baton Rouge, where we examined the bullet holes from the gun that killed Huey Long. The trip to the capital was compulsory, the price to pay for the grand prize: New Orleans.

Forty children filled the tour bus that took us from the train station to the corner of the French Quarter. Rain fell as if poured, turning the view from the bus windows into a fun house mirror that reflected and smeared the flashing lights from the bars lining Bourbon Street. Stranded on the bus by the sudden downpour, we watched the narrow streets become streams full of rushing brown water. We had reservations at a historic restaurant, The Court of Two Sisters, a name that sounded to me like the beginning of a fairy tale. The bus driver worried, wiped the fog from the windshield, took off his cap and lifted his arm to wipe the sweat from his forehead. The humidity was a warm wet washcloth that we breathed, our breath coming quick at the glimpse of the French Quarter.

The teacher stood at the front of the bus and told us we would have to walk the several blocks to the restaurant. The bus couldn’t drop us off, she explained, the water was rising, the bus would flood. The busload of children bustled, fidgeted, impending disaster making us wild, our feet shuffling in readiness to bolt from the bus. We must walk down Bourbon Street, she said. We signaled back and forth with wide-eyed glances at each other, the inner dialogue of absolute glee at our unimaginable good luck. Perhaps we understood that if the teacher saw how thrilled we were at such a prospect she would reconsider. We stood straight as little soldiers, ready. She spoke slowly and sternly as if giving us instructions before a test: Hold the hand of your partner, she told us. Walk two by two. Do not look left, she told us. Do not look right. Keep your eyes straight ahead, she commanded.

A long line of children marched two by two down Bourbon Street, all pinafores and Mary Janes, all buzz-cut boys and busterbrown banged girls, eyes straight ahead, sweaty hands grasping sweaty hands.

I don’t look left. I don’t look right. I look up.

The bright white legs of a woman shot out from the second-story window of a bar, and then disappeared. Then again, the legs flew out, puncturing the grey sky with bright white. A naked woman on a swing soared above my head. Before my very eyes! Naked as a jay bird, I tell it later, conjuring the ten-year-old girl who marched to The Court of Two Sisters through the flooded streets of New Orleans toward what she couldn’t imagine: a flaming dessert, flambeau. Waiters in tuxedos, Madame? Trout amandine, merci!

Once in the movie theater I saw New Orleans spring up alive before my eyes. In the same theater in Shreveport where I’d seen The Wizard of Oz and the Elvis movies, I saw Easy Rider, the road trip two long-haired, dope-smoking, acid-dropping guys made through America on Harleys, the first “alternative movie” I ever saw. For much of the movie the characters were heading toward New Orleans, trying to get to Mardi Gras. As the two neared Louisiana I heard Shreveport in the mouth of one of them, heard it described as a place that was dangerous for outsiders, a place to avoid for people who were different and didn’t fit in, a town to bypass on their way to Mardi Gras. I staggered out of the theater, blinking in the suddenness of the bright afternoon sun, the shock of the radiant understanding that I was in the wrong place on earth.

I was a seventeen-year-old hippie. I’d bought every bit of my hippie paraphernalia on my trips with my parents to New Orleans. Like the hippies I’d read about in Life magazine and saw on TV and in the movies, I went barefoot, everywhere: to the Stop & Go, to the drugstore. When I’d leave school I’d leave my shoes behind. The soles of my feet turned hard and black. I wore a leather choker with red and white beads and a single earring, a gold heart from India, bought from a vendor in Jackson Square.

Bare feet and beads announced my political affiliations: I was against the war in Vietnam; I was for integration; I liked sex and hated Nixon. I imagined I was on the journey with those easy riders, decked out in feathers and beads and bangles, long hair wind-whipped as they — we — rode south from Colorado to New Orleans. Crossing into north Louisiana, the peaceful ride becomes full of menace and violence, and the easy riders decide to circumvent Shreveport.

It is like an emergency broadcast break, a public service announcement: Stay Safe. Bypass Shreveport.

How, I wondered after that, could I get out of there?

My father took me year after year to New Orleans, took us in his big blue Buick out of Shreveport due South until hash browns gave way to grits, brown coffee gave way to black, the spiky shadows of the pines gave way to the dark twisting forms of oak. I was delivered into a world where an aunt lived on an avenue called Elysian Fields, a pot of coffee perpetually on the stove, a slim cigar in her ashtray, and a thick New Orleans’ accent with which one story after another was told.

There was and still is an imaginary line that splits North and South Louisiana, somewhere around Alexandria, the middle of the state, and the split is political and religious. In South Louisiana you have the Democrats and Catholics; in the North there are Republicans and Protestants, mostly Baptists. As a child in Shreveport I had watched from the riverside as people draped in white smocks were walked into the river, where their sins, their many, many sins, were washed away. In New Orleans the spires of the Catholic churches were as filigreed as wedding cakes, and inside, incense and altars, Mary in flowing robes, Jesus, blood and tears, both sensual and spiritual.

When I was in college in Baton Rouge, my boyfriend Geoff and I drove often to New Orleans, driving deeper into the state, where dancing and drink were integrated into the everyday. In Shreveport one had to be sneaky to be sinful.

Geoff and I had met when we were both fourteen. We had first seen each other across a bonfire in Shreveport, at a field party, where kids gathered in cotton fields and pecan orchards to drink, smoke, kiss, do wheelies on motorcycles, preen and prance for each other. I’d swayed between the fire and him; he held up both hands to steady me, then let go and laughed. “Who is she?” he asked the people he came with.“Who is he?” I wondered, holding a cold can of beer to my cheek to cool the heat from the popping orange fire. I was told he was trouble.

We had turned fifteen together — our birthdays only days apart — then eighteen, twenty-one, all the watershed years, years in which we had gone from drinking beer to smoking pot to drinking single-malt Scotch. We had hovered on the cusp of transitions, balking then bolting forward, together. I’d been the teenage girlfriend, mute by his side, the rail-thin boy with hazel eyes, long blond hair, and a badass attitude. I had been the sidekick who longed to be a main character.

When I moved to Houston and Geoff was still in Baton Rouge, we met in New Orleans, staying in a hotel in the Quarter called the St. Anne’s, a small hotel that had threadbare Oriental carpets in the lobby, a courtyard filled with banana trees dripping purple stamens. As we grew up, Geoff and I grew angry with each other. Perhaps we were really angry about the crossroads coming up, inevitably, before us. He was in law school. I worked in a bookstore, where I devoured books by the likes of Colette and Simone de Beauvoir. I became impassioned, sometimes insufferable. Geoff and I fought and made up, fought and made up until we lost the taste for it.

I never told Geoff about Inez, the powerful woman from a place that sounded like Ambrosia situated near a cemetery who bewitched me, showed me something that I couldn’t put a name to, an intangible sense of what a self might grow up to be. I never saw Inez again after that day when I was twelve, but when I was forty-nine I went to New Orleans on my book tour and my host at Loyola University said, “Two old guys are looking for you. They say you’re their cousin.” These were Inez’s sons, Roy and Bill.

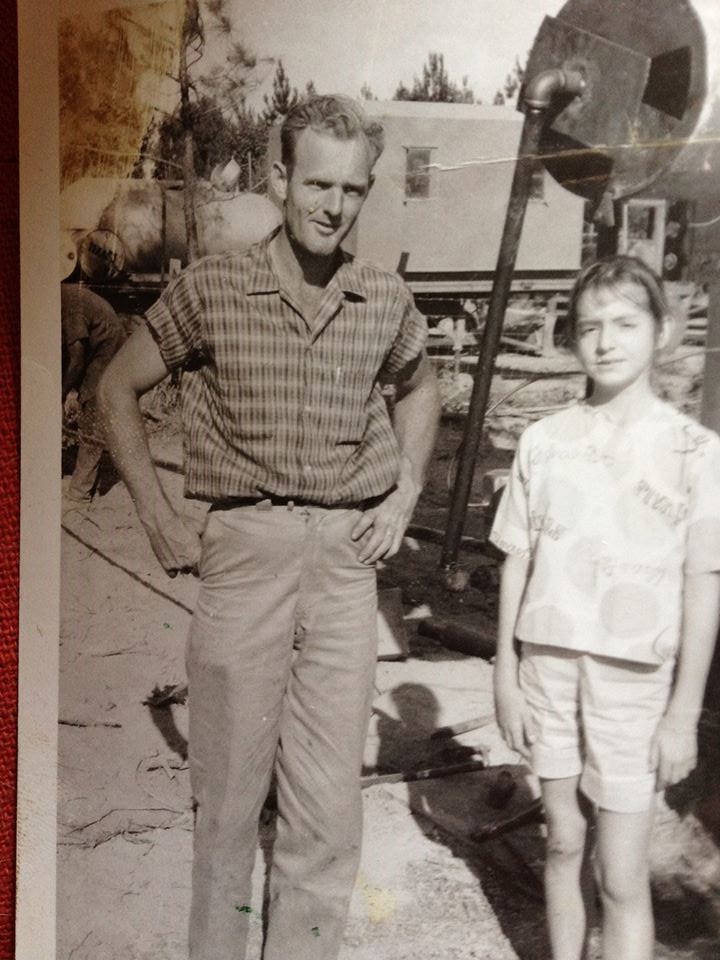

I was about to read from my memoir that is full of New Orleans, its scents and sounds, its spell. From the podium on the stage in a large auditorium, I saw a man walking down the aisle. He had a nut-brown face, dark circles under his eyes, eyes filled with stories to be told, later, at Felix’s, over platters of boiled shrimp and cold cold beer. Twenty-five books, they bought, he and his brother. For each of their children and their grandchildren. They pulled out a sepia-toned photo of my father, a college graduation photo. They were young boys when they were taken to Austin to see the first of any of them not only attend college but also graduate from college. They had this picture all this time, they said. You look just like him, they said in unison, bending forward toward the photo which they gave me.

A year after that, Roy sent me a tape that I would later misplace. After Katrina I searched the house, with no luck, until one morning in January I discovered it in a basket in my study. Barefoot and still dressed in my nightshirt, I went out to my car to listen to it. Roy’s deep voice filled my car as he asked his mother, Inez, questions about growing up in New Orleans. I imagined Roy, a cup of coffee cradled in both hands, leaning forward in his chair toward Inez, whose stories, he was afraid, were going to die with her.

“So you moved to San Antonio and thenVictoria for a while, right?” he asked.“But then you came back to New Orleans. Why was that, Mama?”

The tape hissed and crackled during the long pause.

“Homesick, I guess,” she said, her voice quivering.

As she answered Roy’s coaxing questions, I could see the “picture show” that my great-grandfather owned — The Isis — where my father’s father played drums at intermission. “And we’d walk down Toulouse after the show,” Inez said. “You could in those days, you know. We’d stop at the store on Magazine and get a sack of pastries.” To go with the coffee, I said aloud to myself as I sat in the car, hand to my head, eyes closed, listening to what is most important on the tape, the tenderness in Roy’s voice as he spoke to his mother, whose past clearly was slipping from her grasp. What remains? I wondered as I listened to the to and fro of Roy and Inez. Not the theater. Not the bakery. In the midst of my own reverie there was another crackling silence. Then Inez’s voice — frustrated, weary.“I’m not doin’ too good here, am I?” she asked Roy.

“You’re doin’ jus’ fine, Mama,” he said. “Jus’ fine.”

To connect with Roy and Bill in 2002 was like plugging back into an energy force. I’d spent a lot of time in the last five years in New York, where I have many writer friends. When Roy and Bill found me, read me, my inner gyroscope became recalibrated, and again, often, I headed south to New Orleans for weekends. I stayed with an old college friend, Julia, and her husband, both of whom worked at Loyola, and who, on my visits, spread the options out before me like platters of the most sumptuous of Louisiana delicacies: Zydeco or blues or jazz or R&B? Shrimp or crawfish or crab or catfish?

Now Julia’s house is full of mold, the ground floor flooded, the breaker box wet. She and her husband cook on the grill in the backyard, use candles to find their way to bed, camp out in the second floor of their home. Roy’s house on St. Charles is intact. Bill’s house in Metairie is gone. I think of all of their homes and hear the thin frail voice of Inez, “Homesick, I guess.”

What do we call them? This was the question that swirled around semantics in the first weeks after Katrina. Refugees. Evacuees. Displaced persons.

Exiles, I thought.

When the exiles from Hurricane Katrina arrived in Houston, my friends from Louisiana and I gathered together, had dinners, felt a kinship with the people swept away, the people arriving in bus after bus to the Houston Astrodome. I tried to teach my writing classes at the university, but there was a thickness to my existence, as if I were bundled up in a thick blanket, the way I felt after my father died. A month after Hurricane Katrina, a colleague at the university stopped to chat as I sat on the steps of the library. I said the semester had been hard, that I couldn’t watch CNN anymore and I couldn’t not watch CNN. She told me she had never been to New Orleans, that the place was abstract to her. I was stunned.

A week after Katrina there were three of us at dinner, each from a different town in Louisiana. We spoke of the loss of New Orleans, we drank, we began to reminisce: Remember the time we were at Galatoire’s on a Sunday? I asked them. Yes, yes, we said, and as a group we placed the pieces of the story together: There were the old elite, men with canes in Brooks Brothers’ pin-striped suits, women wearing hats, tables full of people at eleven in the morning with drinks put before them the color of sunsets. I had taken the French bread out of the basket and held it in the air. This big, I said, referring to my lover, waving the large baguette in the air just as the gasp of breath and peels of laughter and our realization that the elegant waiter stood at attention, poker-faced, right behind me.

At eighteen I lost my virginity on a roll-away bed in the Holiday Inn in the Quarter. I was celebrating Mardi Gras. At thirty-five I stayed at the Royal Sonesta on Royal Street with a famous novelist who was married. At forty-nine, The Bienville House, the man a musician, the one who found his way into the last paragraph of my first book. It was not a city I got lost in. It was a city where I was always finding something or finding something out or being found out.

Many of my friends and I had moved to the booming city of Houston twenty-five years before out of necessity, not desire. Desire was New Orleans.

We were meant to live in New Orleans, we say, but we couldn’t or didn’t because of the corruption and the economy, the racism, the sexism, the leisurely languidness. We had been ambitious, in a hurry. We’d all made the decision to come to Houston after college to make a living, but we often shuttled back and forth to New Orleans, drove or flew Southwest, the puddle-jumper, got there by hook or crook, as they say, to get our fix, to celebrate or to mourn, whatever the occasion called for. So where, we asked ourselves now, did we really live?

Watching Katrina’s havoc played out on TV put me in a jazzed-up state of mind, provoked a mania in which I played music — Dr. John, The Neville Brothers — cleaned closets, went through old photographs and emailed.

As if a storm were brewing in me, I channeled my energy into helping the Katrina evacuees — exiles — who were arriving by the thousands in Houston. One day I’m taking diapers and Pedialite to the Astrodome for the children of the storm that blasted New Orleans and much of Mississippi off the map, and the next I’m taping up my windows as Rita gets a name and a charted course. The storm that destroyed New Orleans was both in me and following me.

It was between the two hurricanes that the emails began to trickle in, the emails from people I’d not heard from in years. I began to understand that to them, the friends, the former boyfriends, I am a remnant of a lost region, a face to a place I consider my touchstone, my lifeline. I opened one email and there was Tom Tracy, who I’d been with in Houston, who had gone off to medical school in Tel Aviv in l978 and wanted me to go. We were twenty-six. I had been waiting for my own acceptance letter to graduate school in literature.

He was a Catholic from upstate New York with a surgeon father, a homemaker mother. There were prep schools and Lacrosse teams on his résumé. He had blue blazers in his closet and drove a big boxy old Volvo.

Tom loved southern. Southern was something he thought I’d eaten, metabolized, was. He wanted that, the thrill of my long drawn out syllables.

He left for the school in Israel straightaway, then wrote he wanted me to join him. I knew I wasn’t going to Israel. I wasn’t going to Albany. Now Tom has three boys who look just like he did at twenty-six. He sent the photographs over the Internet while Hurricane Rita changed directions in the Caribbean. There was one photograph of a black-haired boy holding a Lacrosse stick that swept me back into that place where I was so wild with love.

Tom of today, Dr. Tom Tracy, head of pediatric surgery in Providence, Rhode Island, wanted to have me air-lifted out of Houston because he was “certain” I’d think I could tough it out as Rita was bearing down. He had friends, he wrote, at Texas Children’s. He could get me on a helicopter! Where did he want to put me? I wondered. Out of harm’s way, he must have thought. Over yonder, my mother would’ve said. I’m not very transplantable, I told him over email, just as I’d told him more than twenty years before.

I have a photograph in my study, a black and white of me in the backyard of my house. I wear a vintage house-dress, half on, half off, and I’m hidden in the ivy, behind the ferns in the yard that is more lush Louisiana than landscaped Texas. Huntley, who was from Kansas, took this photograph for his final exam in Photography 101. Right before he took the picture he hollered, Stella!, and I turned and grinned, caught.

Huntley, who had been my younger man, nineteen when I was thirty, who is now in the first year of his third marriage, also emailed me as Rita swirled in the Gulf. Remember “our” hurricane? he wrote to me from his office in Dallas about Hurricane Alicia. “Can you believe there were no cell phones and no email then?” he wrote.“We were so disconnected,” he said of the days after the 1983 storm when the power was out for weeks. During that storm, Huntley had been across town while I was in my apartment with my “real” boyfriend.

That was Geoff. Geoffrey Reed Pike. My Louisiana boyfriend.

Geoff and I finally called it quits for good when we were twenty-nine.

I left him for the first time in New Orleans, left him in the St. Anne Hotel, and moved down the block to the Prince Conti. We’d quarreled, as we often did, this time in the Old Absinthe Bar, the thousands of business cards, yellowed, pinned to the wall, the place like a ship’s quarters, beneath the sea, the mahogany bar rich and dark. On our way from the bar to the hotel, I felt we were swimming through the dark waters of the Quarter, unsteady on our feet. Back in the room we were a maelstrom, both full of accusations and bitterness. While he was in the shower, I packed my bag and walked out and down the street as the sky turned from black to violet. At the new hotel I ordered my first room service. I ate Eggs Benedict, drank chicory-laced coffee, and reveled in my nerve. It was the first time I’d left him, but not the last.

The storms of Geoff ’s past: The man with the sax. Tom Tracy. Huntley.

For the last twenty years Geoff has lived a few miles from me, has two sons, an ex-wife, and a girlfriend. He is the executor of my will, the person to call if my home security system is triggered. We list each other on the forms that ask whom to contact in case of an emergency. Some nights when I’m at his house and his girlfriend — and before that his wife — has gone to bed, we put on Tom Waits and open another bottle of wine and sometimes we argue over who did the most wrong. “I was a prick,” he says. “No, no,” I’ll say. “Me, it was me. I was terrible. I was despicable.” Then we look down at our drinks, look up, move on.

In the days before Katrina, I called him and he called me. In the days before Rita, he called me and I called him. With the impending storm, and in the aftermath of the first storm, there was urgency to our calls, a shorthand that we spoke. He tells me of his hurricane plan. If all the power lines are down, he says, I will come to you. I will walk down North Boulevard, then go down Mandell, and turn right on Marshall. We will only walk down these certain streets if there is terrorism, vandalism after storms, no email, no telephone, no water, trees felled, lines downed. We will only walk this certain route and we will find each other. I imagine us walking up and down these streets that have now become country lanes, covered with brush and limbs, soft with leaves. It is both the apocalypse and Brave New World. It is a pastoral dream of Eden. Things will be simple. We will meet each other halfway, for the first time in our lives.

A silver net of memory pulled these men toward me and I saw glimpses of my past, shiny, like rain backlit by street lights. I felt the pull of these men as the barometric pressure began to press in on us in Houston as we waited and watched for the storm of the century. The images of disaster in New Orleans had clouded our judgment, our ability to reason. We were pulled this way and that: stay or leave. That is what it all comes down to, came down to, I thought, as I read the influx of emails. Should I stay or should I go?

I hunkered down in my home in Houston. I walked my property line, a small inner-city lot, a stucco house built in 1910, where townhouses are enveloping and surrounding my leafy life. I looked at each tree around my house, touched a palm to trunk, to bark, as if to leave an imprint, to say goodbye when — not thinking if but when — they were toppled by Rita’s winds. Like I did as a child in Shreveport to get to sleep, I lay in bed the night before Rita made landfall and counted the trees, beginning with those on the left and moving to the right around the yard: elm, maple, ash, pine, oak, camphor, redbud. Then I’d begin again, going right to left, tree by tree, the ritual, the repetition, a gathering of my forces, magical thinking.

Rooted or paralyzed? I got updates on New Orleans on the Internet. The trees on St. Charles are still standing, I read. I rejoiced. The African parrots that roost in the palm trees are gone, along with the palms. I sobbed.

The last time I was in New Orleans was in May. My brother, my younger brother, my baby brother, had died in the spring. I went there to hear music at the Jazz Festival, hoping to find solace, making a pilgrimage, carving out a space in which to remember him when we were friends. I was not welcome at the funeral in Shreveport. My brother had hurt his child and I had written about it. The boy was sixteen when he ran from his father, my brother, and came to my home in Houston. I’d seen the damage, lived with the damage my brother and his wife had done to a child, and I’d written about it, published it for all the world to see. At book clubs I’m asked if I have regrets about the book, “Would you do it again?” people ask. I don’t know, I say, I can’t know. I won’t ever know for sure. It is constant, the accounting I do. The reckoning — right or wrong?

During my three days in New Orleans I bought art: an angel seated in a bird’s nest; a strange ceramic girl in a white box; a photograph of a young black boy curled within some floral sheets, black and white. My acquisitiveness was like hunger. I stuffed my suitcases, shipped some pieces, felt these might fill the gap my brother left, leaves.

I danced with a roomful of people at Irma Thomas’ club, took the white handkerchief she gave out for her grand finale, waved it over my head in the conga line, sang along with her. There were only a few white folks at the club and when we caught a cab we begged to go to an after hours club. I can’t stop dancing, I thought. If I stop I will have to know my brother is dead. We had not spoken in ten years. Our story was gothic, Faulknerian, the reviewers said when they read of my estrangement from my brother in the memoir. I’d written of his gambling, his gypsy life, the debt, the wife he met in a mental hospital, their child, taken by the courts, who later came to me as a boy, a Goth boy, black clothes, black heart.

New Orleans is where I once walked the streets with my adolescent brother. We went down Royal and came back with treasures — metal soldiers, old chess pieces. We found the palm reader I’ll return to again and again who then shook his head, looked morose and frightening. We went to the railroad tracks next to the river and came upon a drifter who tried to catch us, holding out his penis and laughing. Breathless and frightened, we ran back to the hotel, comforted by the maroon paisley plush carpet, the coziness of the café where we ordered fried shrimp po’ boys and Dr. Peppers. We had liked each other once, my brother and I.

I went that spring to New Orleans, the spring before the summer storm, to walk the same streets we had walked together and to say goodbye to my brother.

Natural and unnatural disasters have been the beginning and the end of my coming into print. Like a hand reaching out from under water, I write now of a city washed away, the place where the exotic became familiar to me, the place where the magic horn was the back-up music for my own stories, artifacts I hope to be receptacles, repositories of short stories of love and lust. Carnival and carrying-on. Craving and querying. Rhythm and revelation.

It’s been a rainy night, night after night since the place I loved has turned from green to brown. I feel the trees downed, the roots ripped, black and brown veins, like ganglia branching, the silhouette of their spirits, wild dreadlocks twisting up to the sky, unearthed and exposed like the memories and the metaphors: the houses, the music, the voices, the friends, the family, the brother, the lovers, the city of New Orleans, unearthly, it has always been, will be, is.

Notes

- Faulkner. “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun.

- Memoir. Entitled If Nights Could Talk: A Family Memoir.

Source

Marsha Recknagel. “Between Two Storms.” The Journal Spring / Summer (2006): 7-23. Print.