Lyle Saxon, Robert Tallant, and Edward Dreyer.

Gumbo Ya-Ya.

Preface

Gumbo ya-ya — ‘Everybody talks at once’ — is a phrase often heard in the Bayou Country of Louisiana.

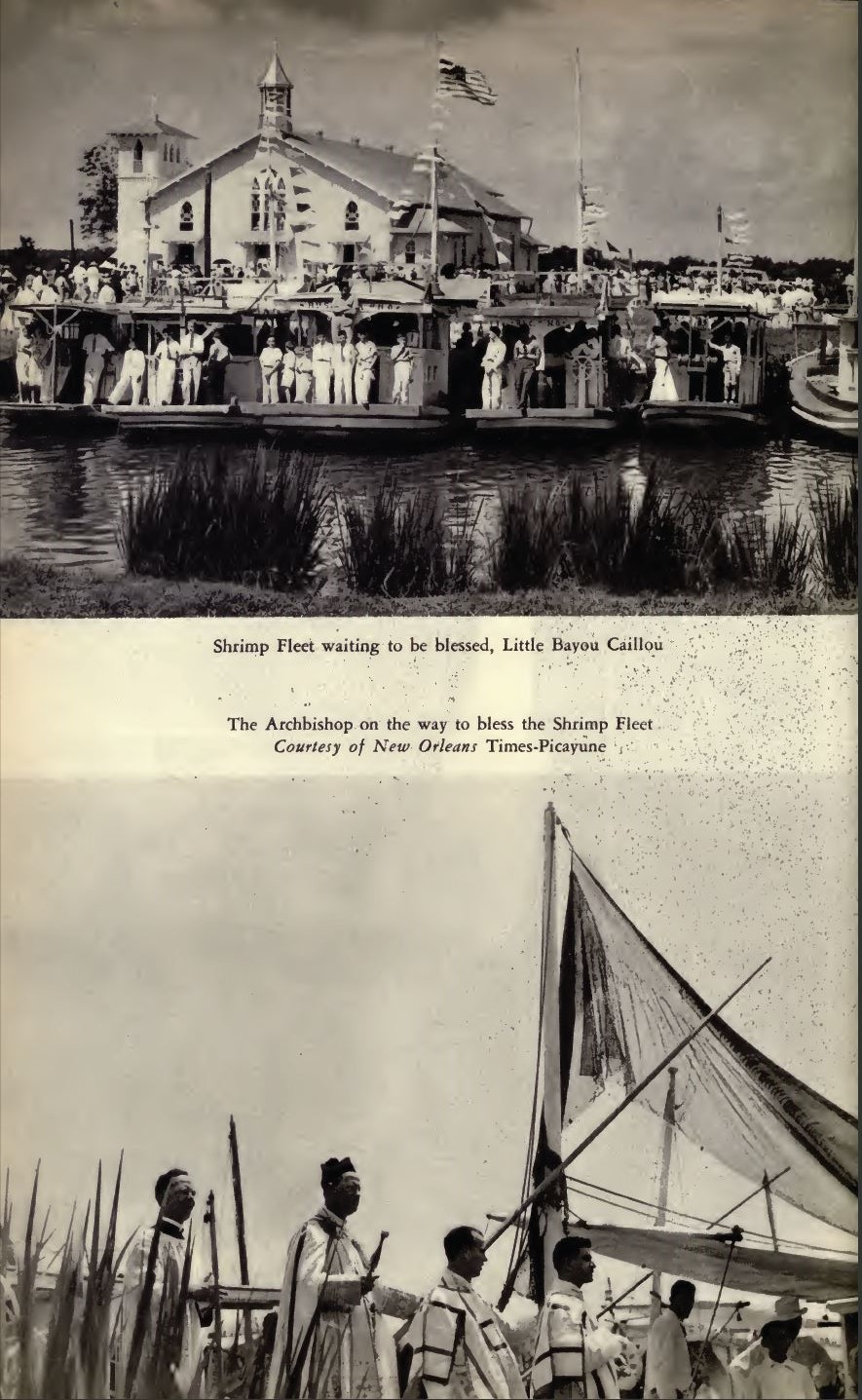

This Gumbo Ya-Ya is a book of the living folklore of Louisiana. As such it is primarily the work of those characters, real or imaginary, living or dead, who created this folklore. We wish to express our indebtedness, therefore, to Madame Slocomb, who was so polite that she invited even the dead to her parties; and to Valcour Aime and the golden plates at the bottom of the Mississippi; to Monsieur Dufau and his ciel-de-lits, and to Tante Naomie, bold in her ‘bare feets’ at the blessing of the shrimp fleet; to the ghost of Myrtle Grove and the loup-garous of Bayou Goula; to Mike Noud and ‘The Bucket of Blood,’ and to Jennie Green McDonald, left alone in the original Irish Channel; to Mrs. Messina, who had everything, including half an orphan, and to Mr. Plitnick, who had the timidity; to Miss Julie, who rouged her roses, and to Mrs. Zito, who made everybody cry to beat the band; to Chief Brother Tillman, for whom Mardi Gras was life, and to Creola Clark, ‘who kept her mind on Mama’; to John Simms; Junior, the chimney sweep on a holiday, and to all the vendors of pralines and calas tout chauds; to Evangeline and to Lafitte the Pirate; to Annie Christmas and Marie Laveau; to Père Antoine and Pépé Lulla; to Mamzelle Zizi and Josie Arlington and the hop head’s love, ‘Alberta’; to Long Nose and Perfume Peggy; to Mother Catherine and the Reverend Maude Shannon; to Coco Robichaux and Zozo la Brique; to Crazah and Lala and Banjo Annie; and to the Baby Doll who had been a Baby Doll for twenty years.

The material for this book was gathered by members of the Louisiana Writers’ Program of the Work Projects Administration. The idea was suggested by Henry G. Alsberg in 1936; he was then the National Director of the Federal Writers’ Program. We in Louisiana were pleased with the idea, and at every possible opportunity assigned workers to the task of collecting the folklore of the State.

The Louisiana Library Commission, of which Essae M. Culver is Executive Secretary, has sponsored this book, as well as the earlier publication, the Louisiana State Guide. The city of New Orleans sponsored our first publication, The New Orleans City Guide.

It may be well to remember that Louisiana was first a French colony, then Spanish, and that the territory was nearly a century old before becoming a part of the United States. It was an agricultural territory and many thousands of Negro slaves were imported. In the plantation sections the Negroes outnumbered the Whites five to one; consequently their contribution to the folklore of the State has been large.

The Creoles, those founders of the French colony, contributed their elegance, their customs, and cuisine. They influenced their slaves and, in a sense, their slaves influenced them.

In Southwest Louisiana lived the Acadians — or Cajuns, as they are affectionately called — those sturdy farming folk who, driven from their homes in Nova Scotia at the end of the eighteenth century, populated that area.

It would seem that the whole of Louisiana was a peculiarly fecund part of the Americas; the forests were filled with birds and animals, the bayous and lakes were teeming with fish, and the Creole mansions and the Cajun cottages were full of children.

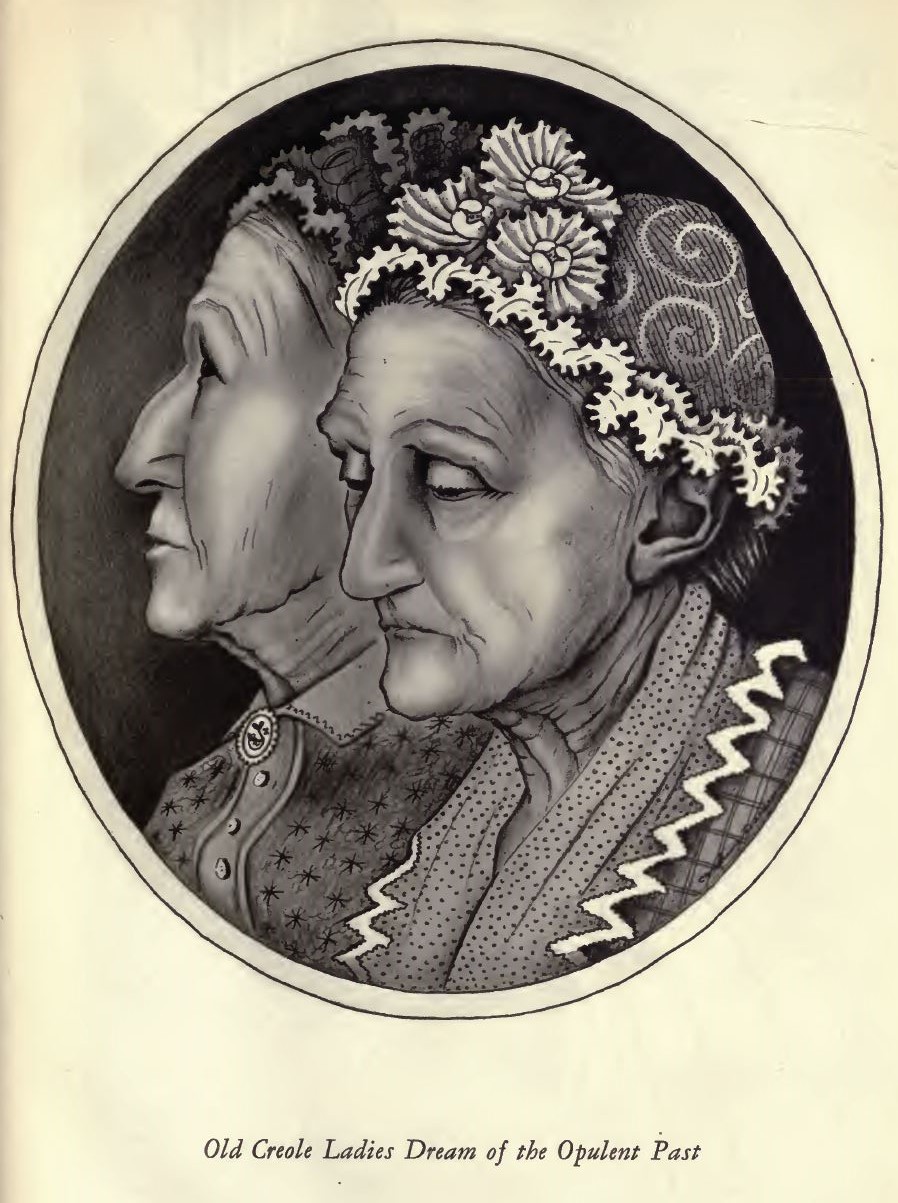

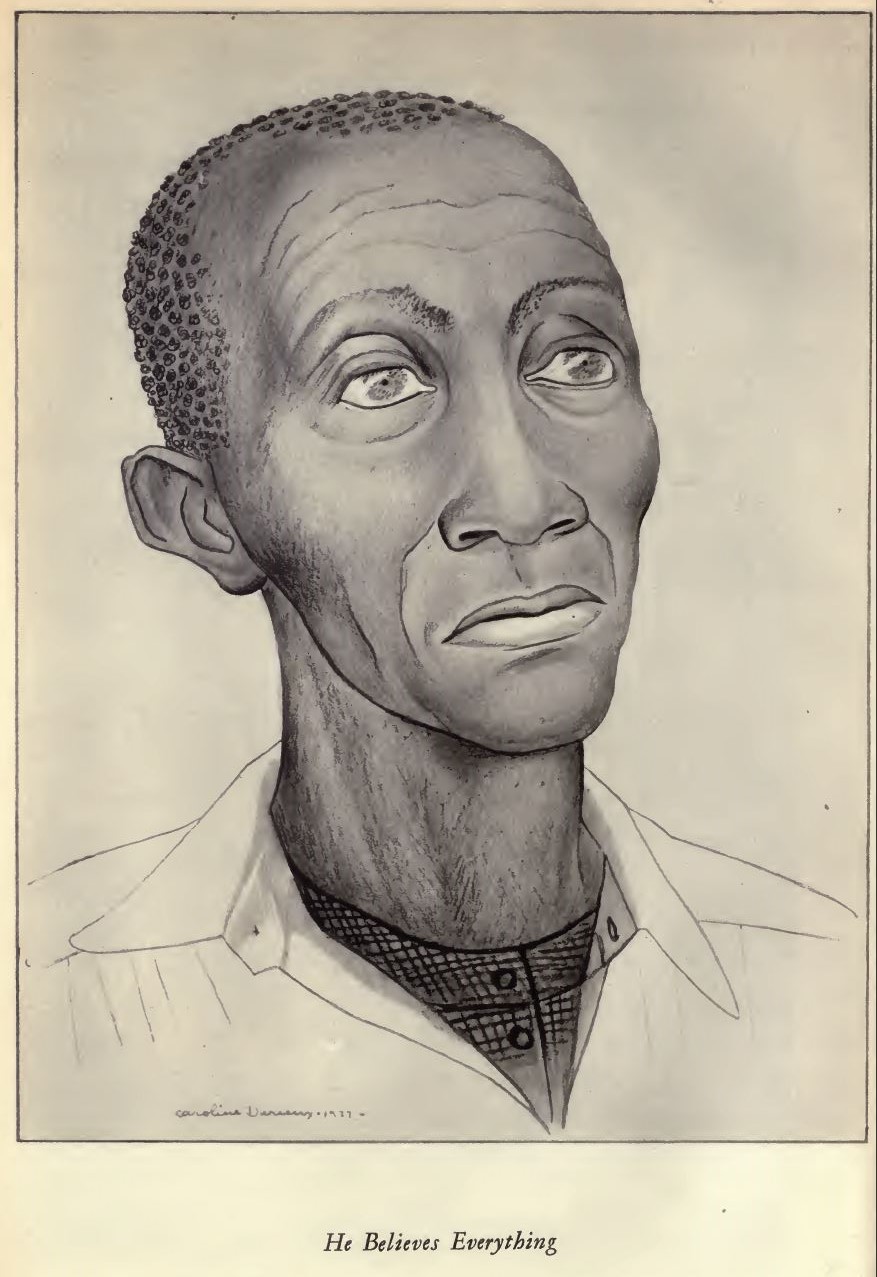

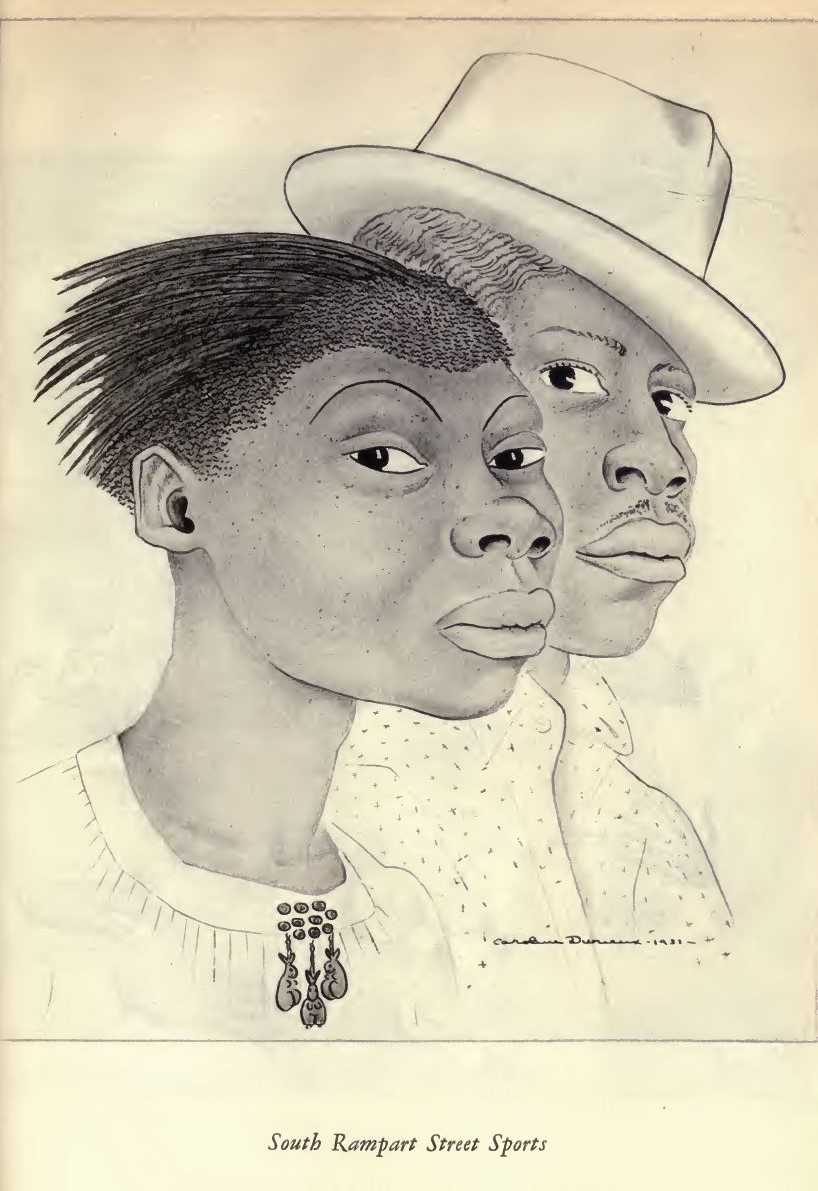

In a leisurely collection of the folklore of the various racial groups, we have attempted to have the collecting of material done either by members of the groups themselves or by those long familiar with such groups. For example, in the stories pertaining to the Creoles much of the work was done by Madame Jeanne Arguedas, Madame Henriette Michinard, Monsieur Pierre Lelong, Caroline Durieux, and especially by Hazel Breaux, who worked untiringly collecting Creole and other lore. Many old families were consulted and their stories, their rhymes and jokes, have been written down here for the first time. We are grateful, too, to Archbishop Rummel and to Roger Baudier of ‘Catholic Action of the South’ for advice and help.

The Cajuns have produced many State leaders, from Governor Alexandre Mouton to Jimmy Domengeaux, the present representative of the Bayou Country in Congress. In this book, however, we have attempted to treat only of those humbler dwellers of their part of the State. Harry Huguenot, Velma McElroy Juneau, Mary Jane Sweeney, Margaret Ellis, and Blanche Oliver worked in those outlying districts.

Much of the information pertaining to the Negro was collected by Negro workers. Robert McKinney gathered most of the material in the chapter entitled ‘Kings, Baby Dolls, Zulus, and Queens.’ Marcus B. Christian, who was Supervisor of the all-Negro Writers’ Project, also contributed to the book, as did Edmund Burke. Many Negroes who were not connected with the Project offered information and suggestions. Among these were Joseph Louis Gilmore, Charles Barthelemy Rousseve, author of The Negro in Louisiana, President A. W. Dent of Dillard University, and Sister Anastasia of the Convent of the Holy Family.

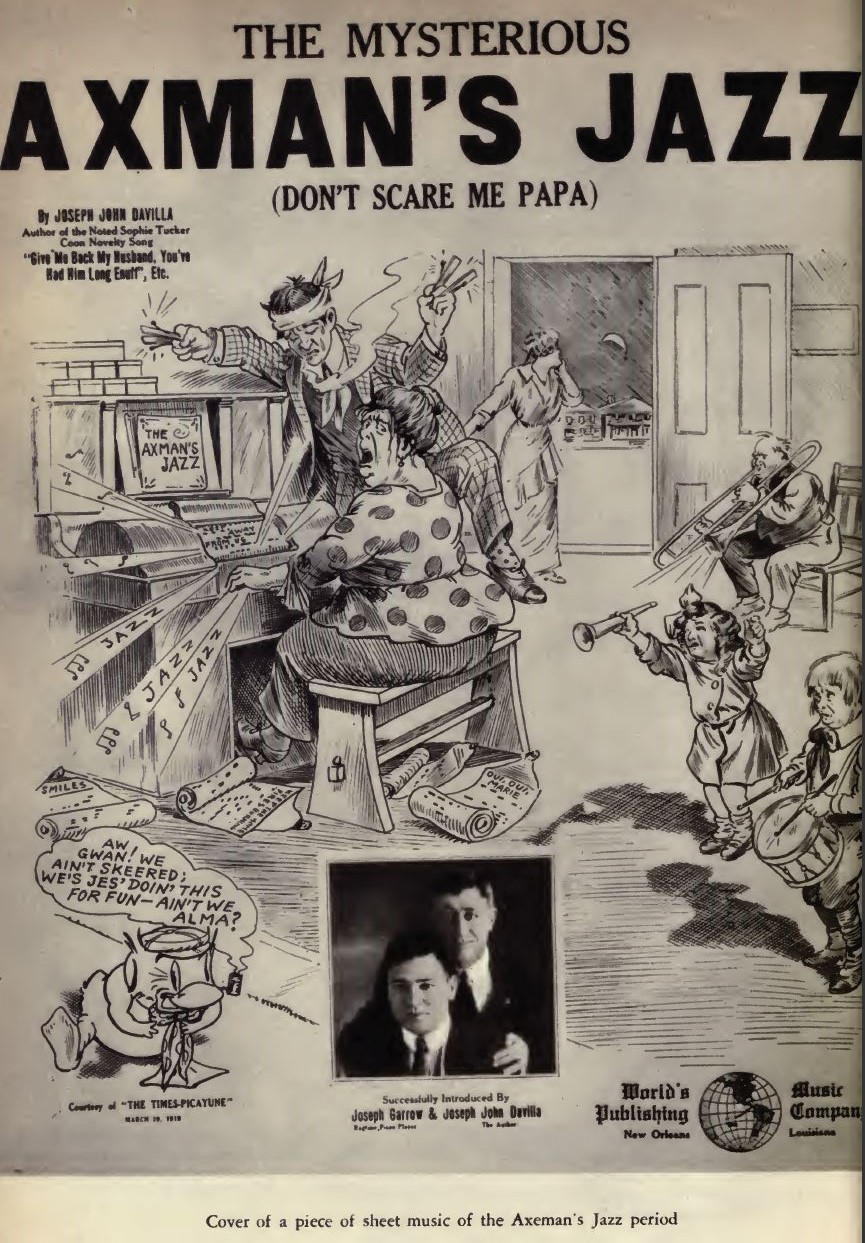

In so far as we know, certain aspects of life in New Orleans have not been recorded before, such as the chapters dealing with Saint Joseph’s and Saint Rosalia’s Day, the Irish Channel, the Sockserhause Gang, Pailet Lane, and the ‘scares’ in the chapter entitled ‘Axeman’s Jazz,’ in which are told the stories of such folk characters as the Axeman, the Needle Man, the Hugging Molly; and the Devil Man. We have attempted also to explain the mercurial and characteristic reactions to these horrors. Maud Wallace, Cecil A. Wright, Catherine Dillon, Rhoda Jewell, Zoe Posey, Joseph Treadaway, and Catherine Cassibry Perkins contributed to these sections as well as to others.

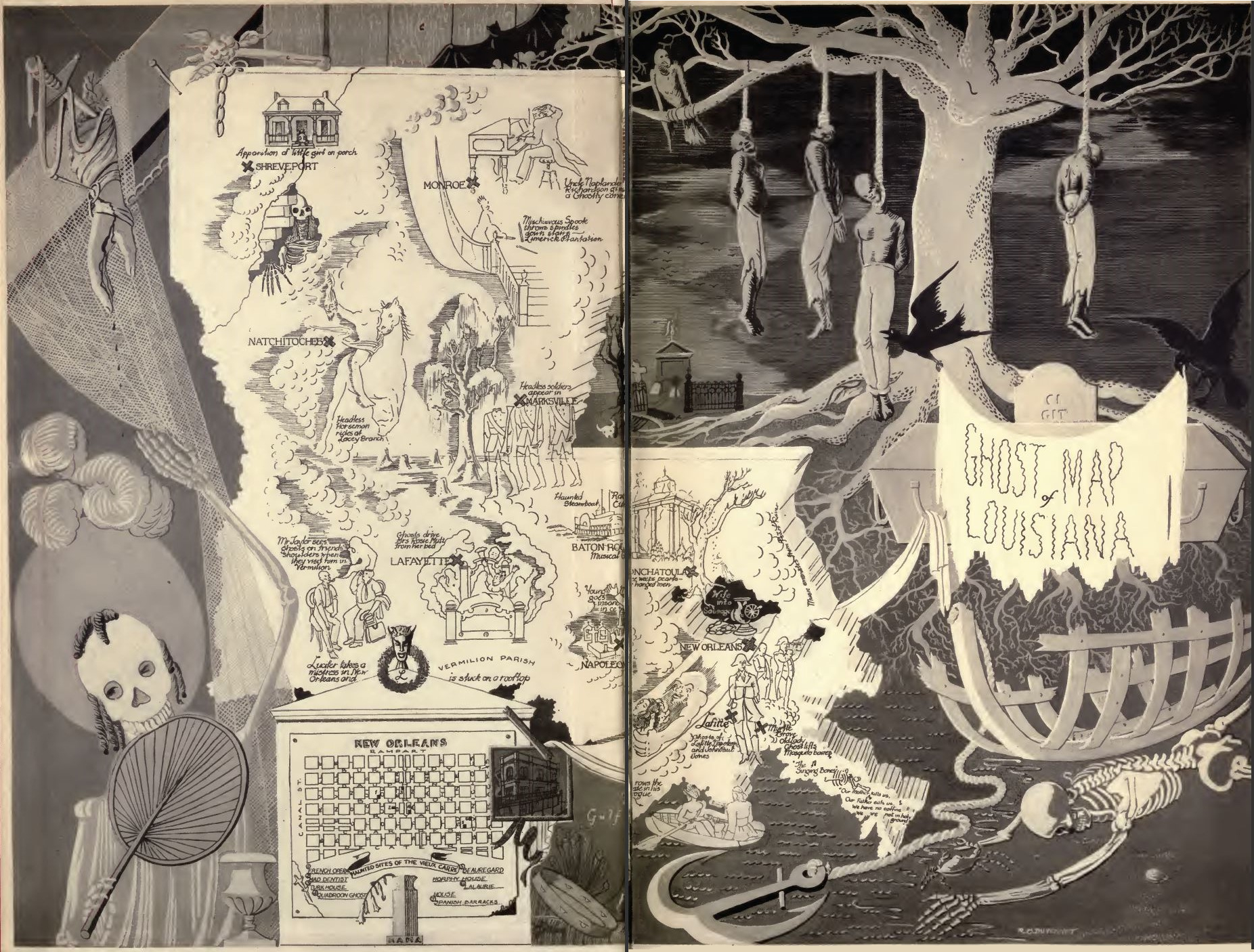

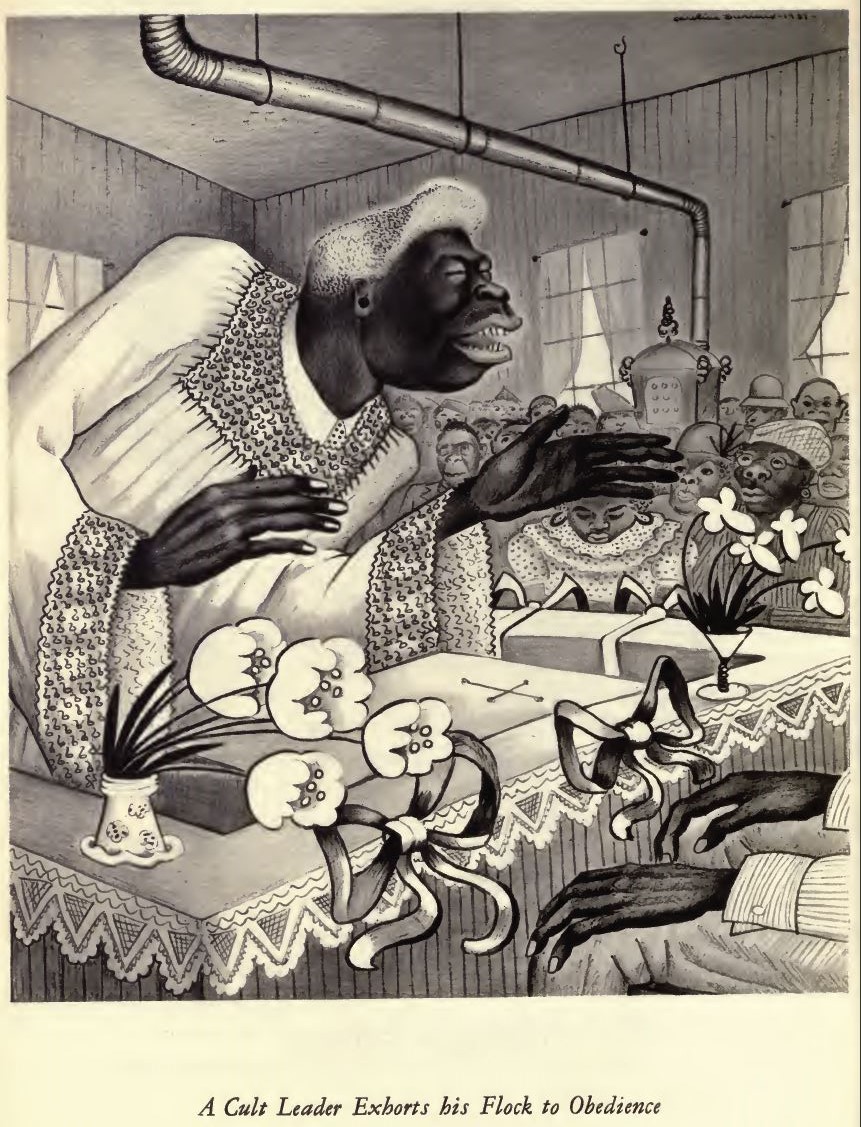

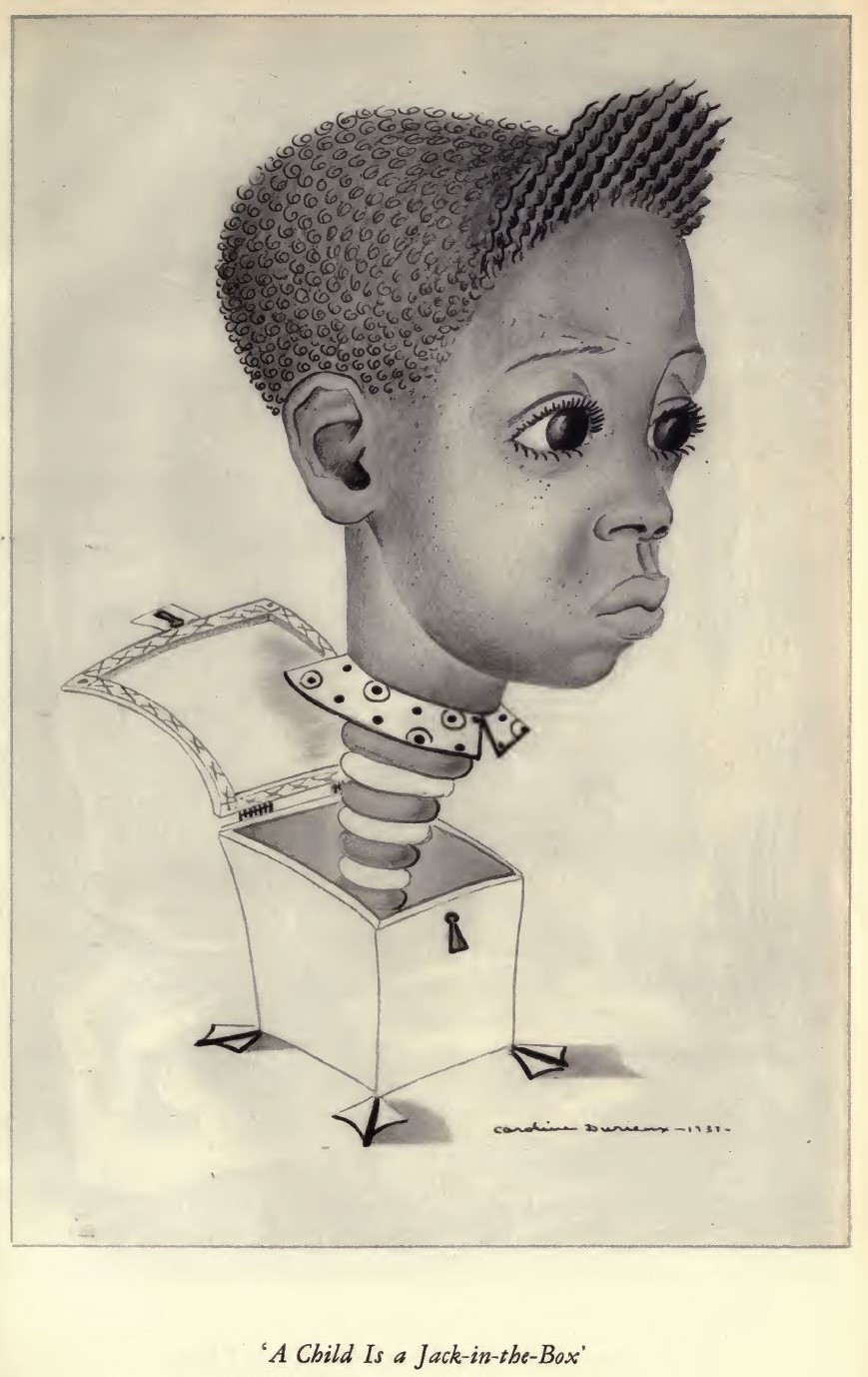

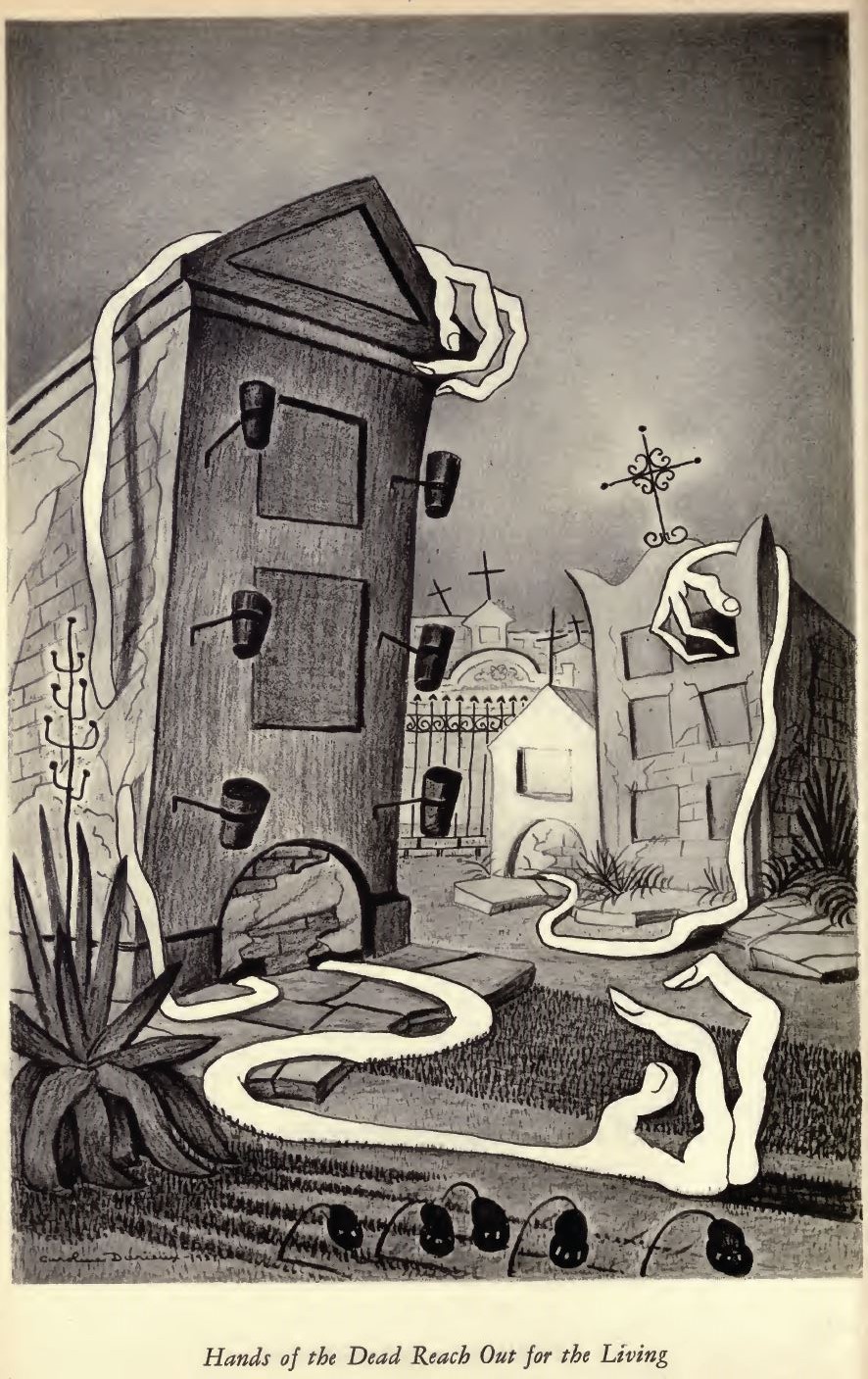

The plates in this volume are from drawings by Caroline Durieux; the ghost map, the headpieces, and the tailpieces are by Roland Duvernet. Photographs, except for those where credit is specifically given, were made by Victor Harlow.

We are grateful to those earlier writers who recorded some of the phases of Louisiana folklore — Alcée Fortier, Lafcadio Hearn, Grace King, and George W. Cable — as well as to such contemporary writers as Doctor William A. Read, Edward Laroque Tinker, Roark Bradford, and Doctor Thad St. Martin.

Edward Dreyer

Robert Tallant

Contents

- Kings, Baby Dolls, Zulus, and Queens

- Street Criers

- The Irish Channel

- Axeman’s Jazz

- Saint Joseph's Day

- Saint Rosalia's Day

- Nickel Gig, Nickel Saddle

- The Creoles

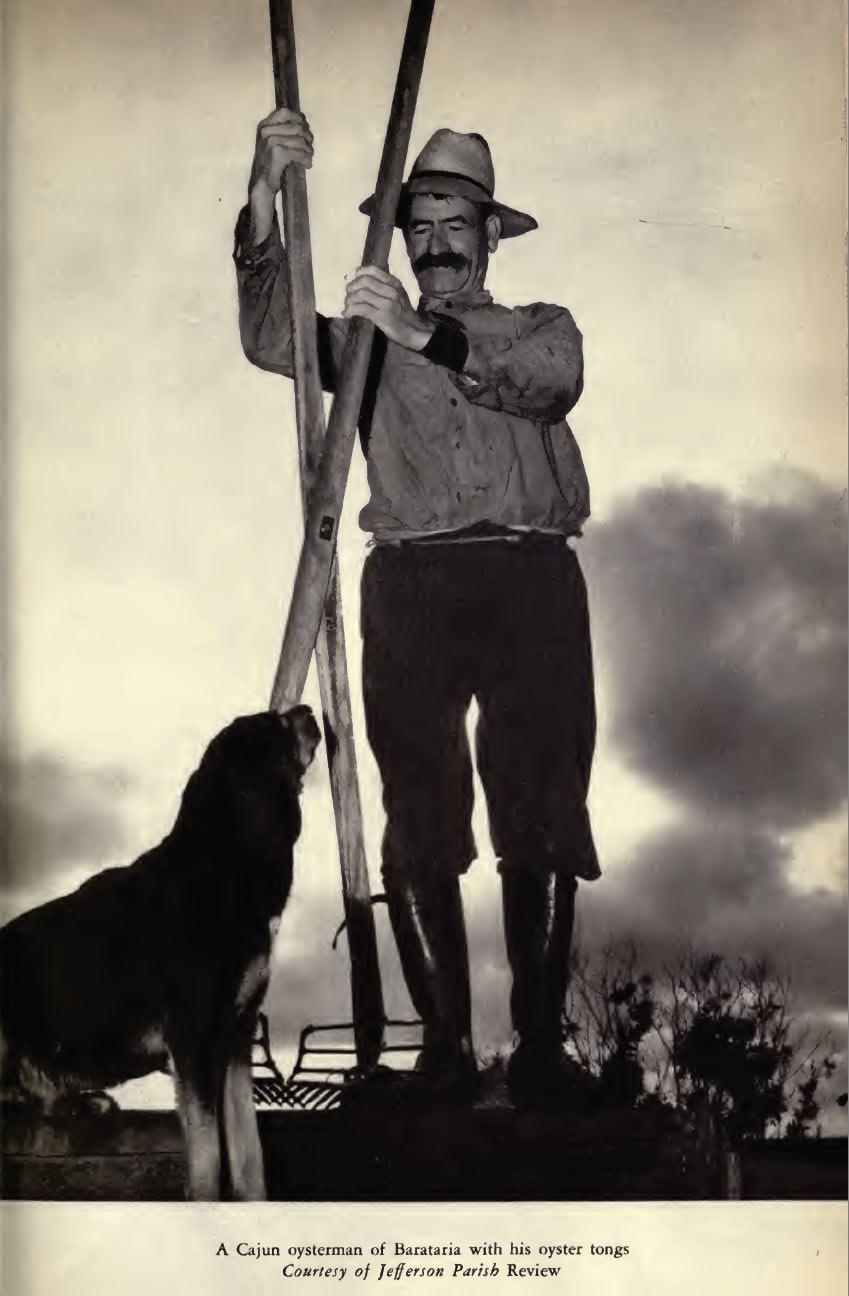

- The Cajuns

- The Temple of Innocent Blood

- The Plantations

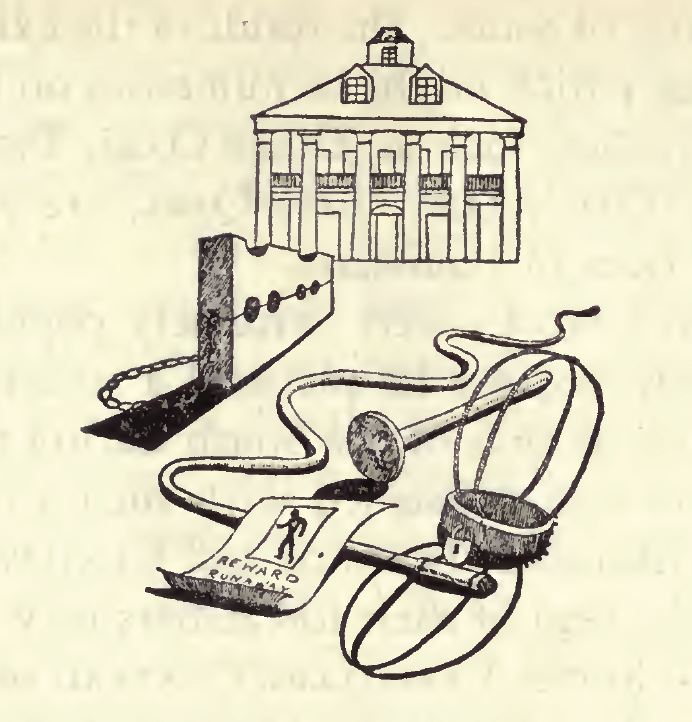

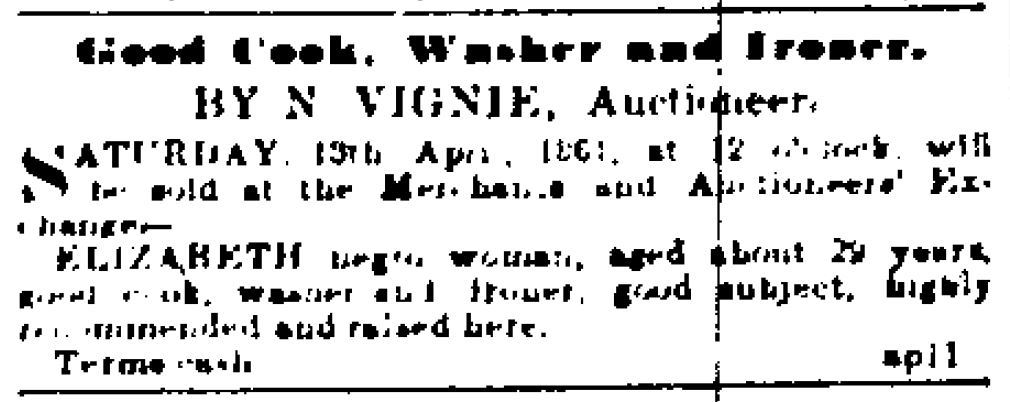

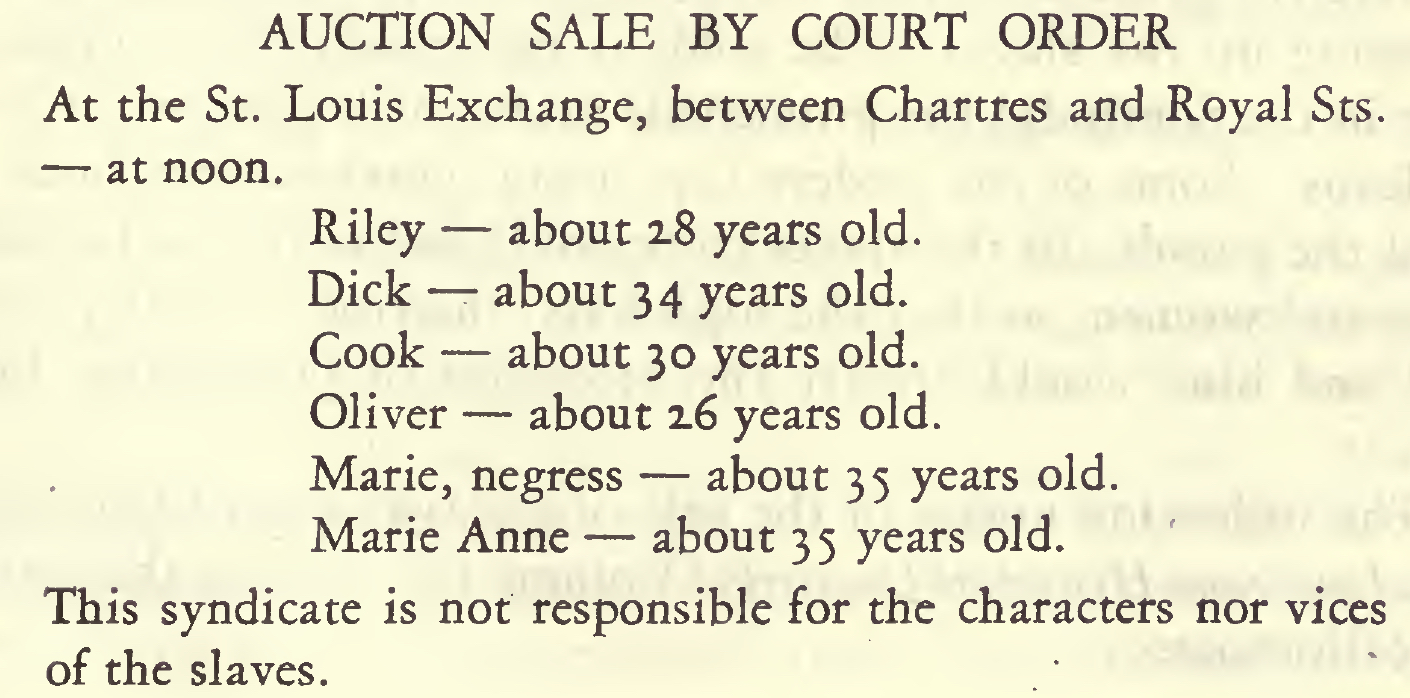

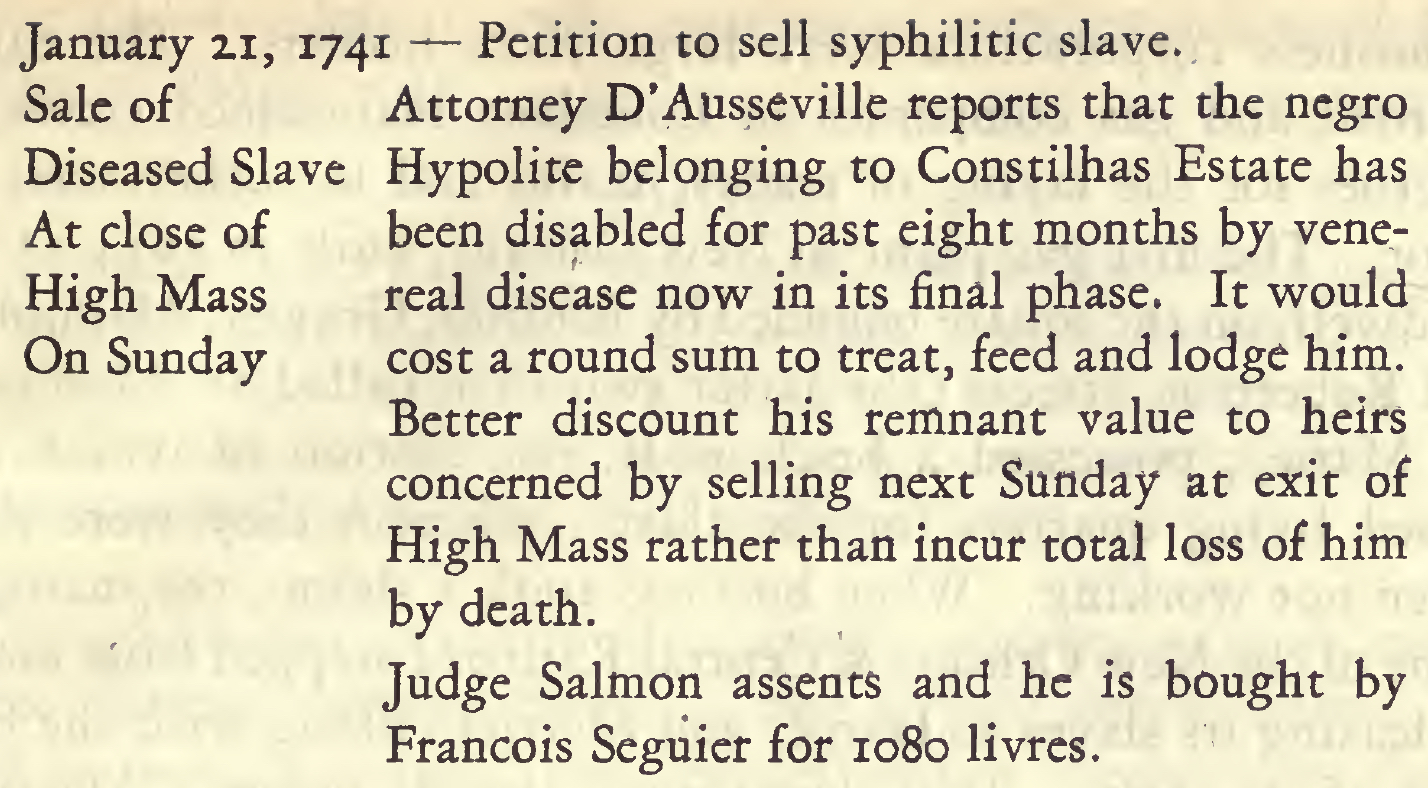

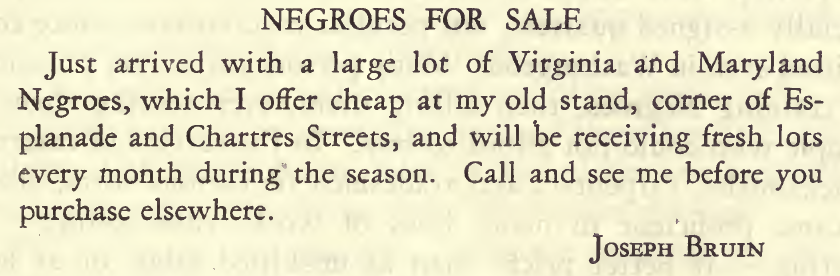

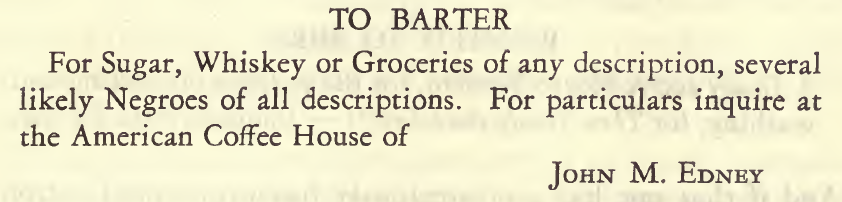

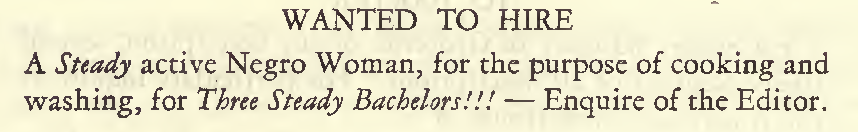

- The Slaves

- Buried Treasure

- Ghosts

- Crazah and the Glory Road

- Cemeteries

- Riverfront Lore

- Pailet Lane

- Mother Shannon

- The Sockserhause Gang

- Songs

- Chimney Sweeper's Holiday

- A Good Man Is Hard to Find

- Who Killa Da Chief?

- Appendixes

- Index

List of Illustrations

BETWEEN PAGE 22 AND PAGE 23

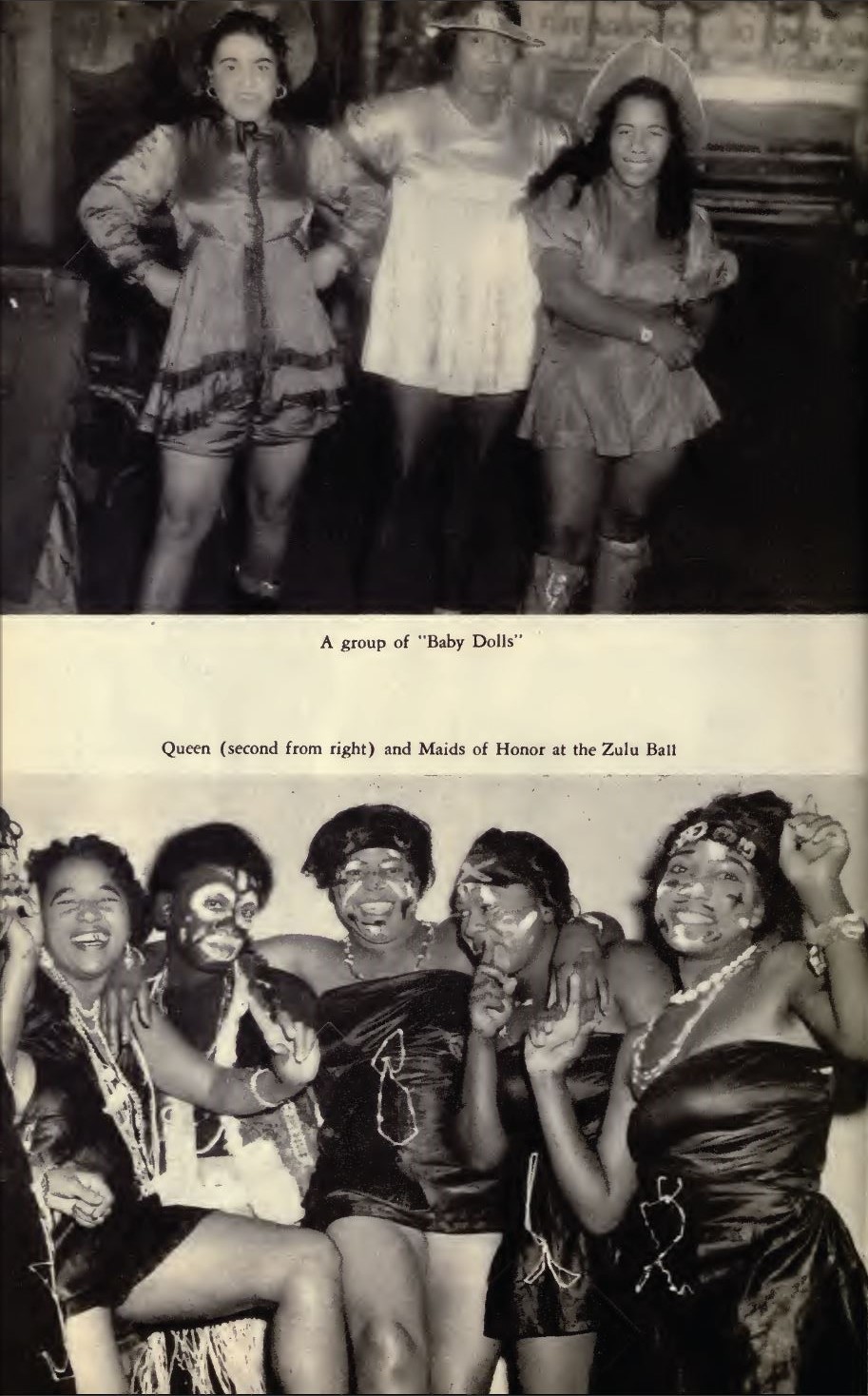

- The ‘Baby Doll’ Appears on Mardi Gras and Again on St. Joseph’s Night

- A Group of Baby Dolls

- Queen and Maids of Honor at the Zulu Ball

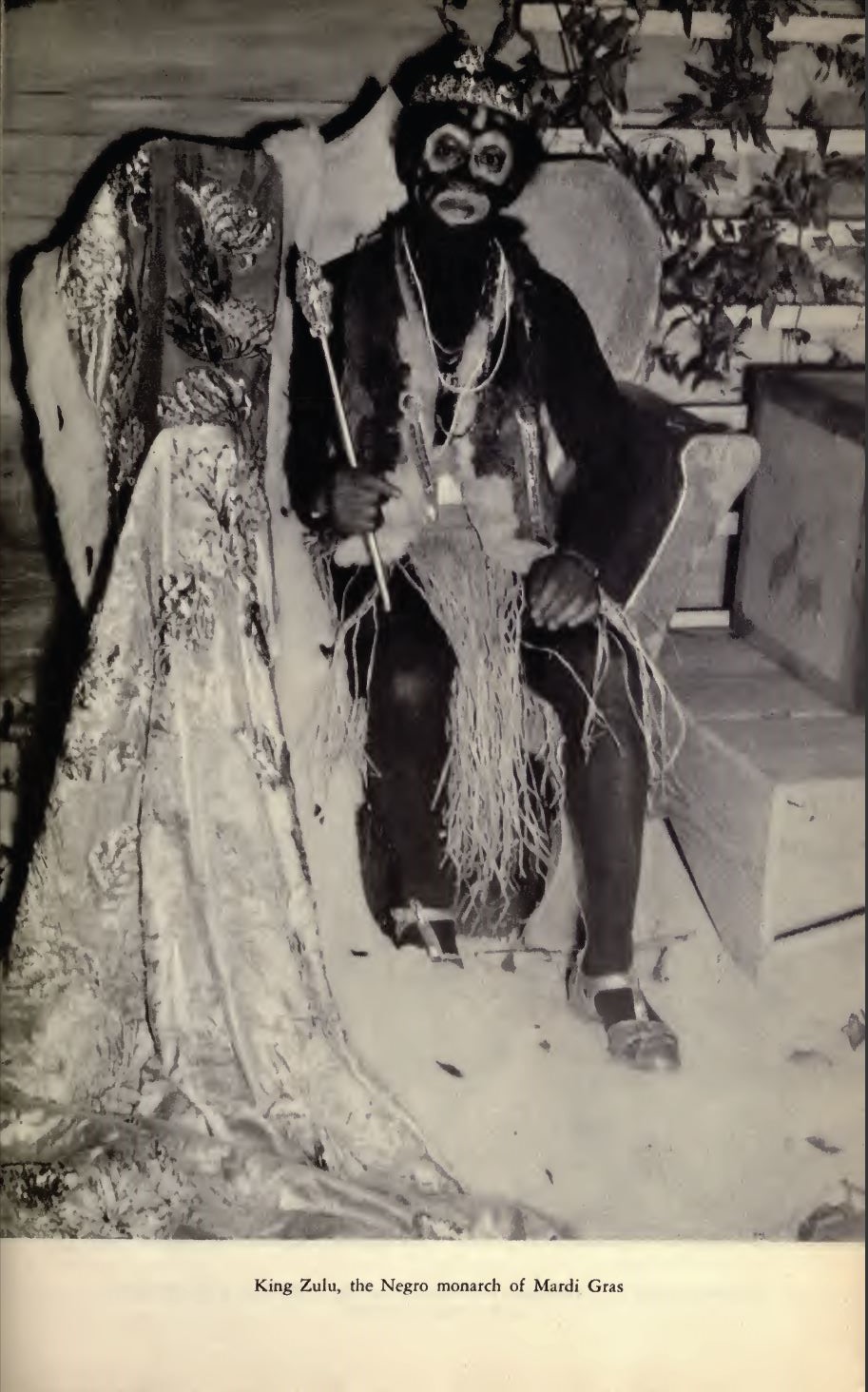

- King Zulu, the Negro Monarch of Mardi Gras

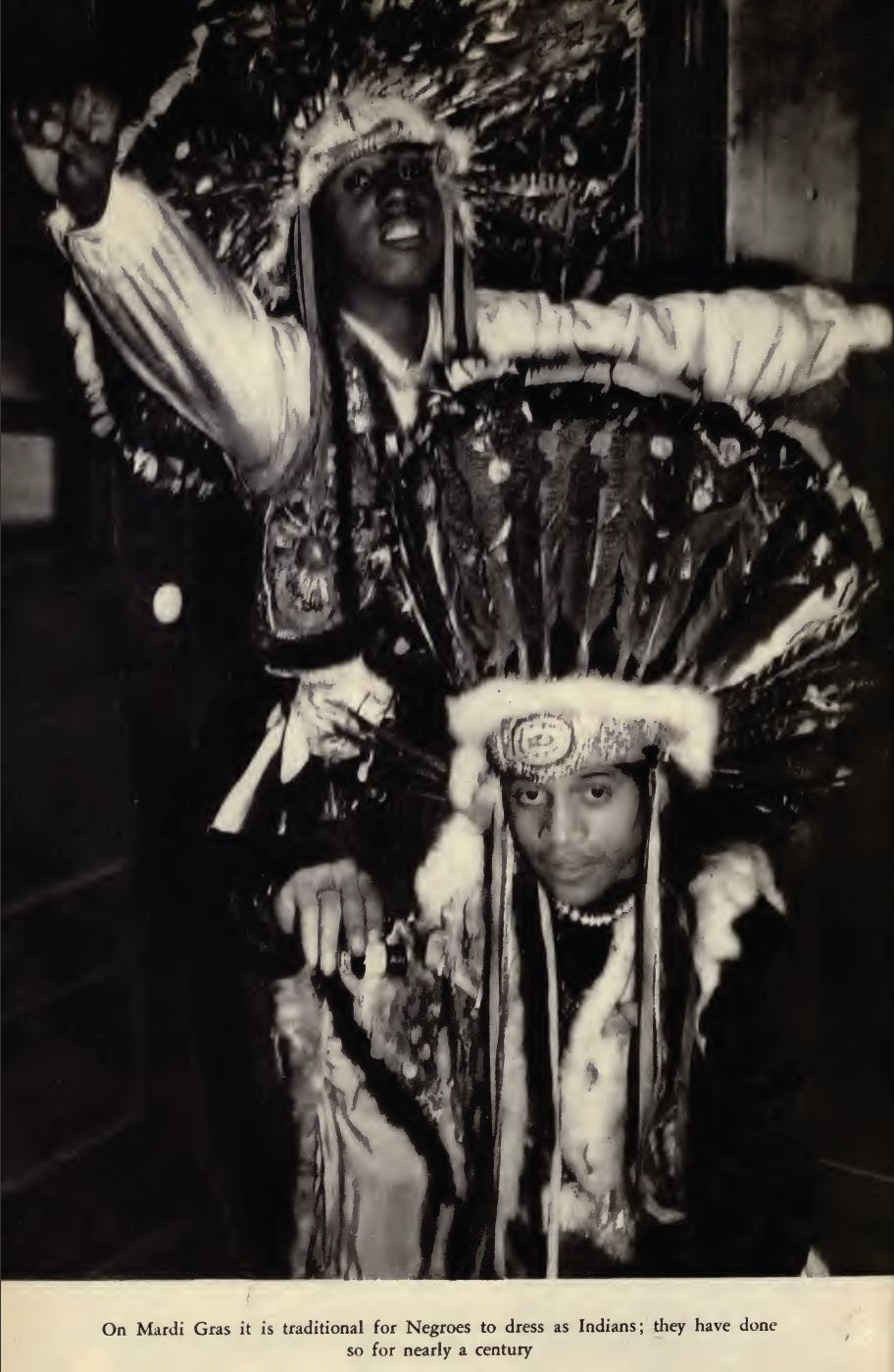

- Negroes Dressed as Indians for Mardi Gras

BETWEEN PAGE 54 AND PAGE 55

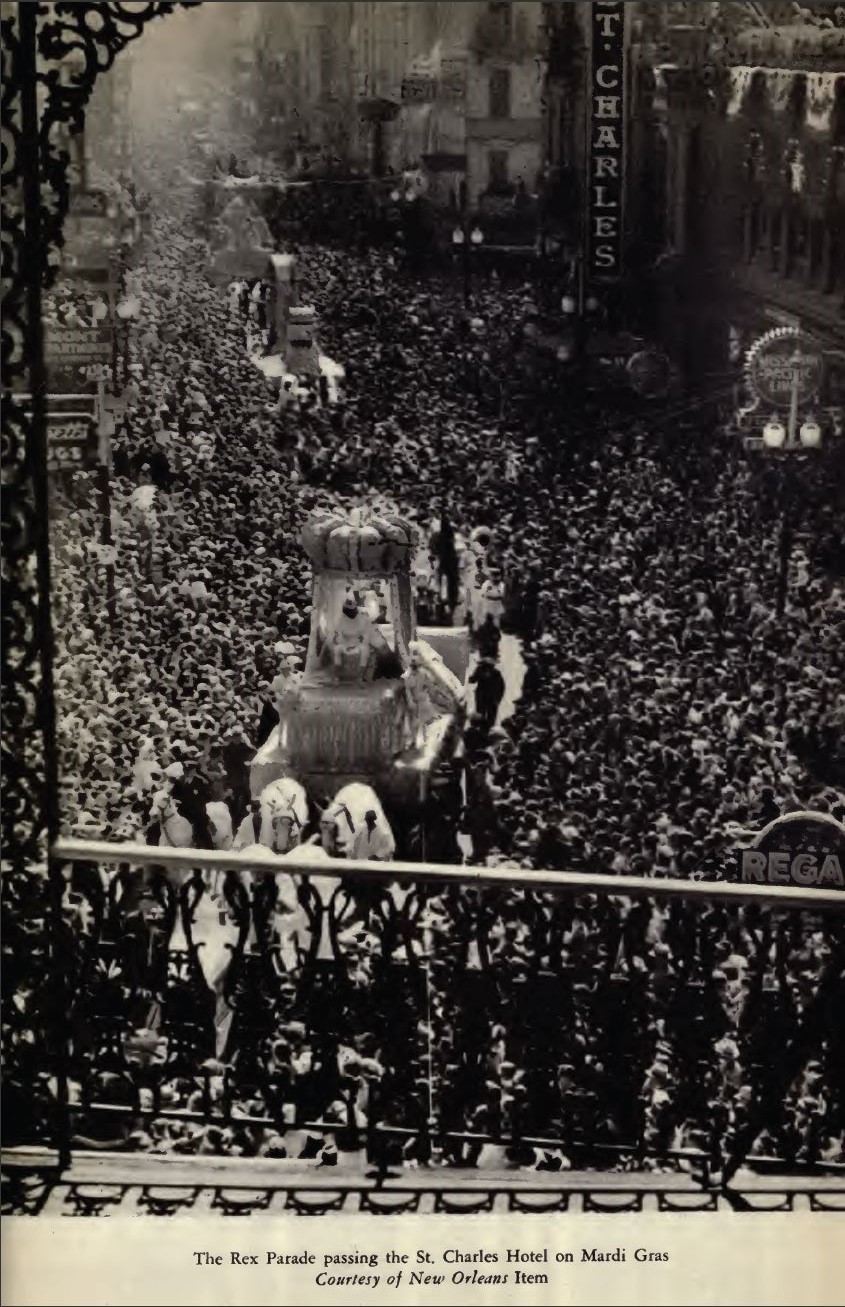

- The Rex Parade Passing the St. Charles Hotel on Mardi Gras

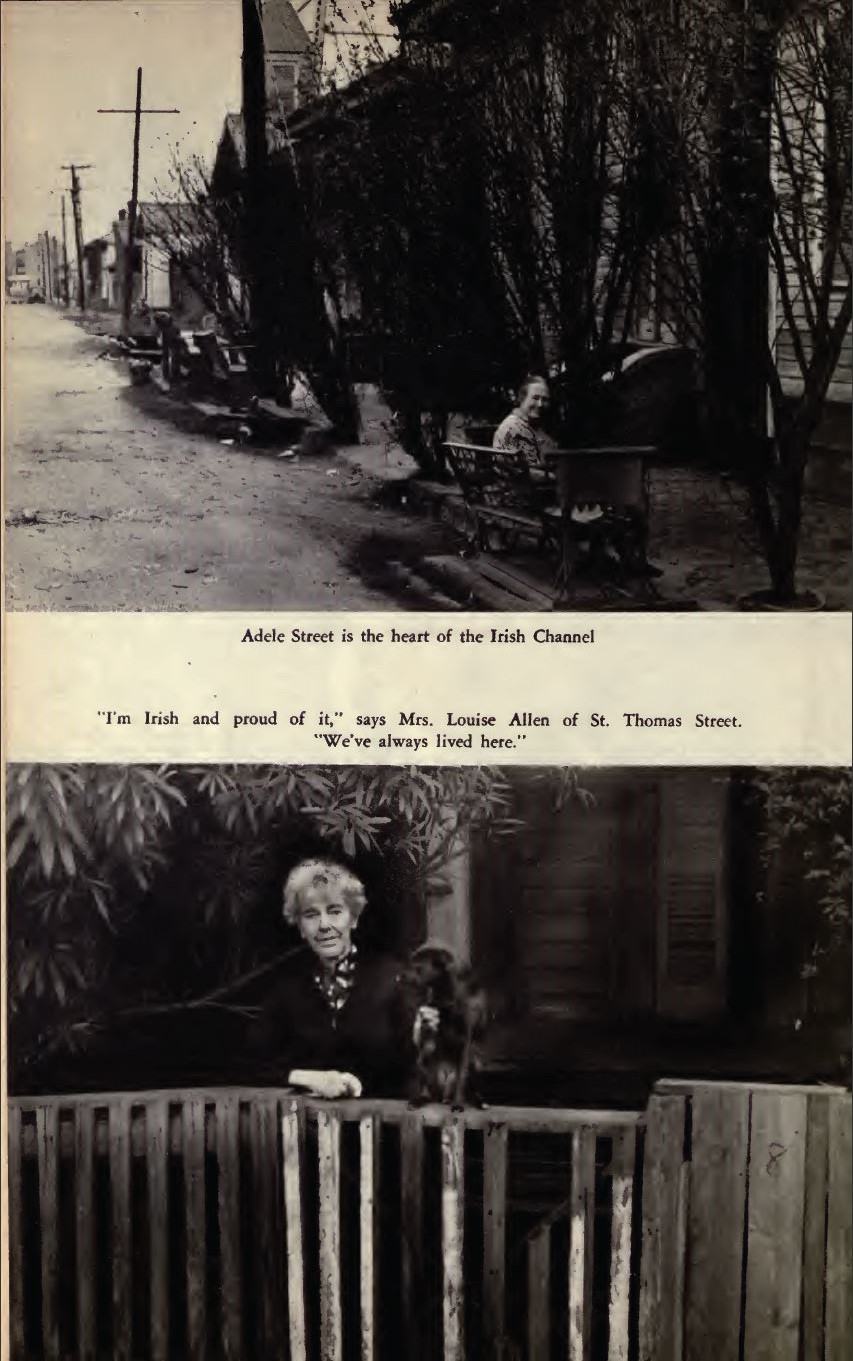

- Adele Street Is the Heart of the Irish Channel

- ‘I’m Irish and proud of it,’ Says Mrs. Louise Allen

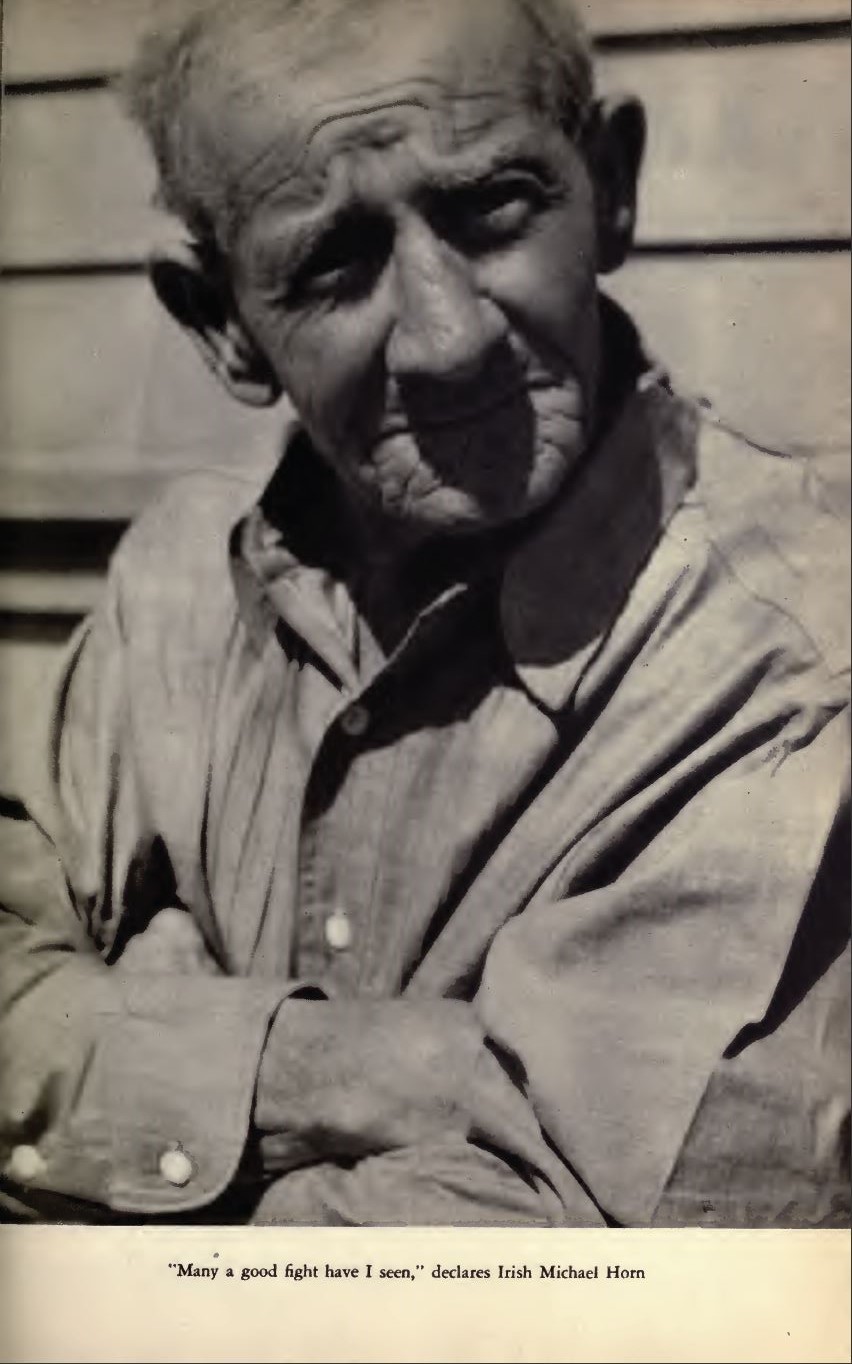

- ‘Many a good fight have I seen,’ Declares Michael Horn

- Cover of a Piece of Sheet Music of the Axeman’s Jazz Period

BETWEEN PAGE 118 AND PAGE 119

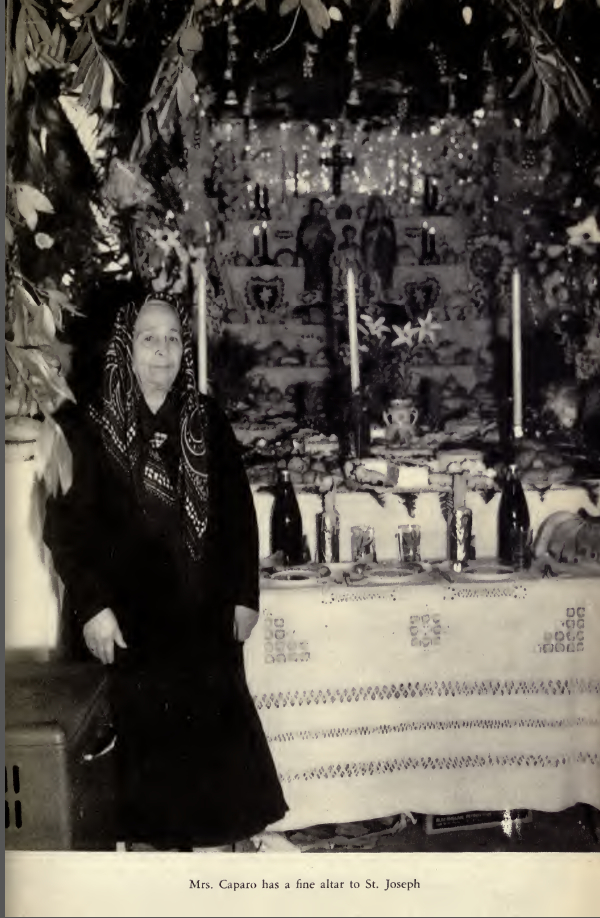

- Mrs. Caparo Has a Fine Altar to St. Joseph

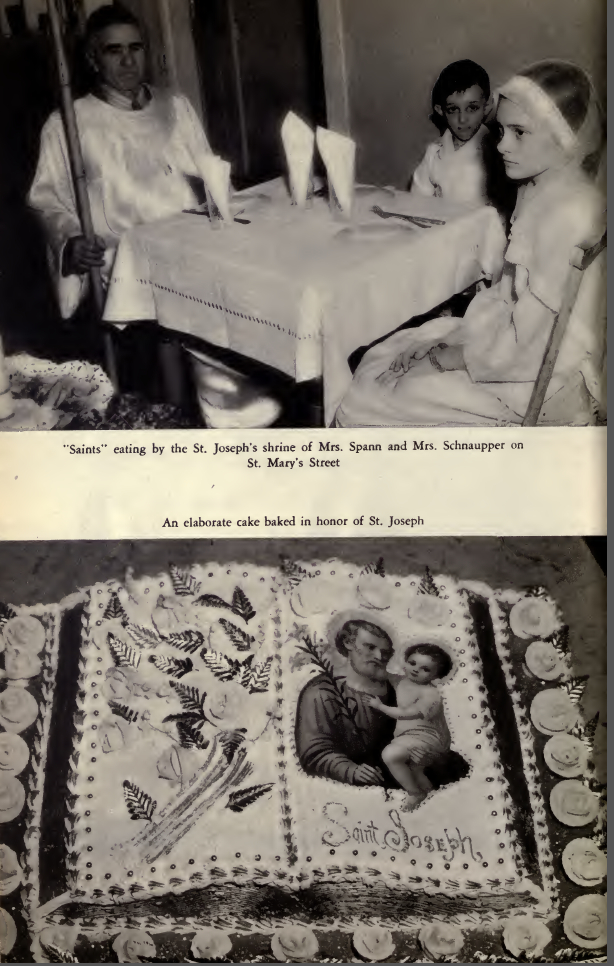

- ‘Saints’ Eating by the St. Joseph’s Shrine

- An Elaborate Cake Baked in Honor of St. Joseph

- Montalbano’s Altar to St. Joseph

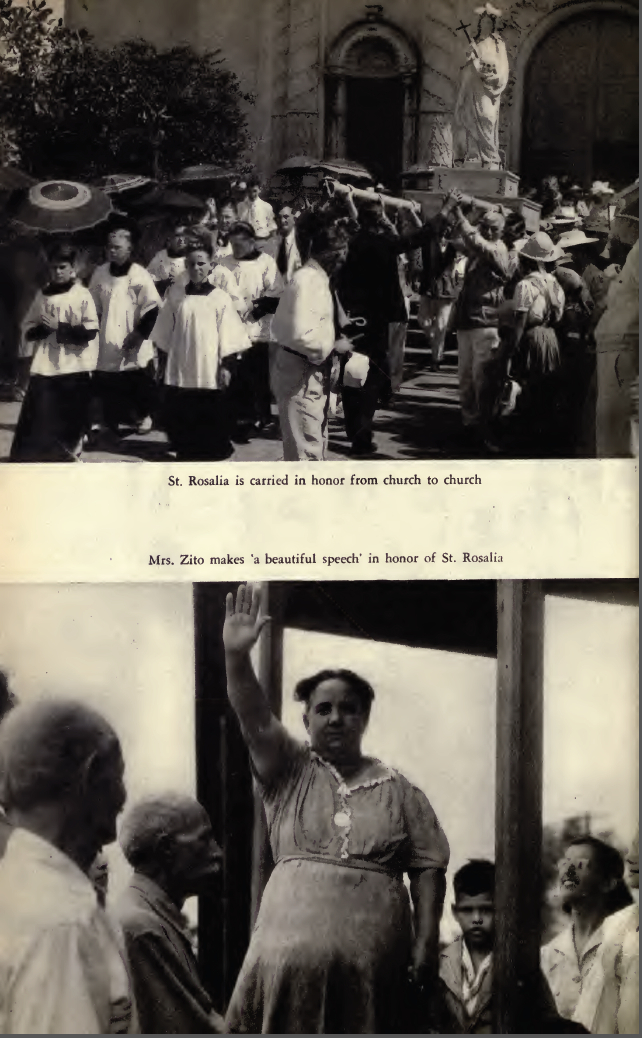

- St. Rosalia Is Carried in Honor from Church to Church Mrs. Zito Makes ‘a Beautiful Speech’ in Honor of St. Rosalia

BETWEEN PAGE 182 AND PAGE 183

- A Cajun Oysterman of Barataria with his Oyster Tongs

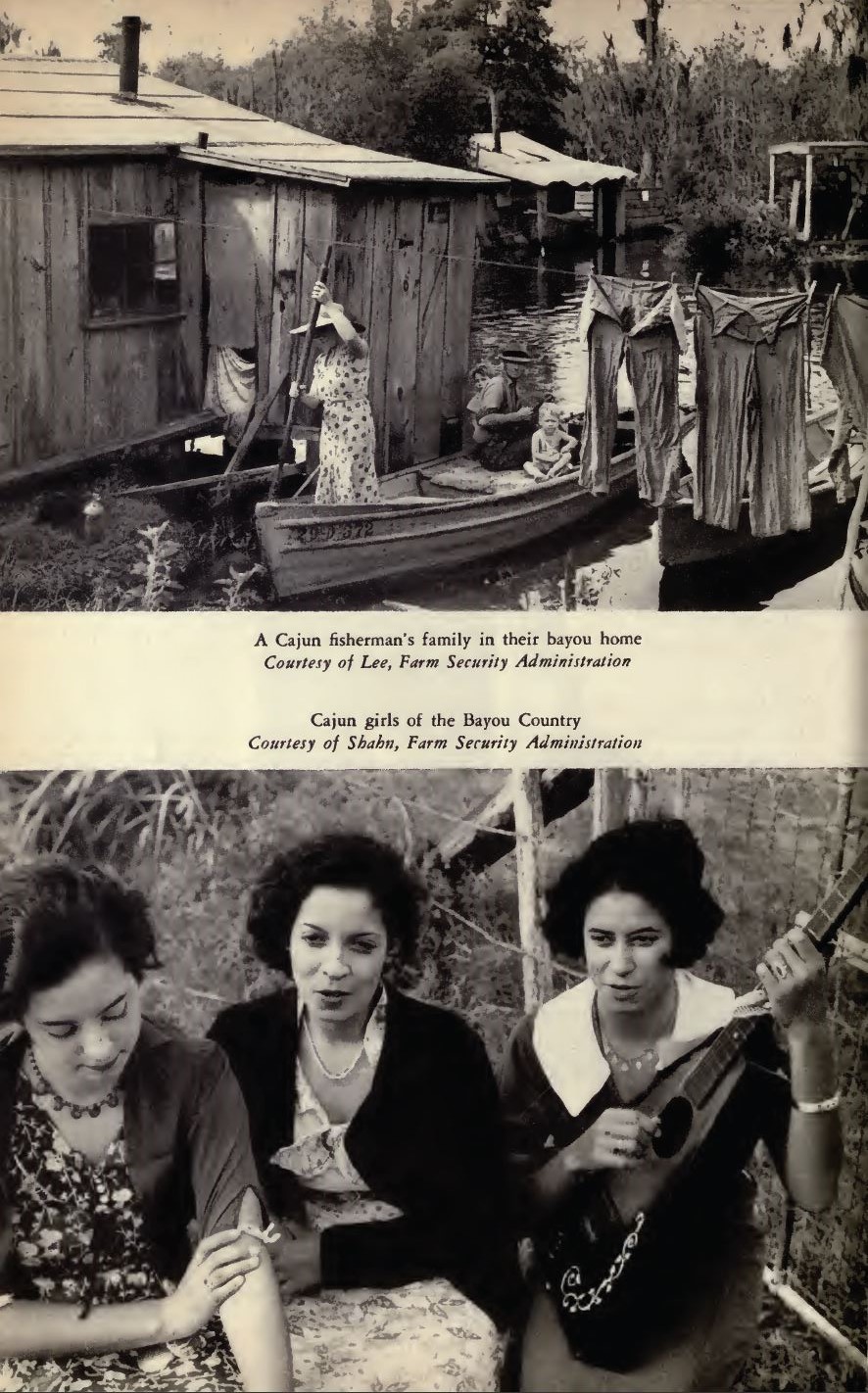

- A Cajun Fisherman’s Family in their Bayou Home

- Cajun Girls of the Bayou Country

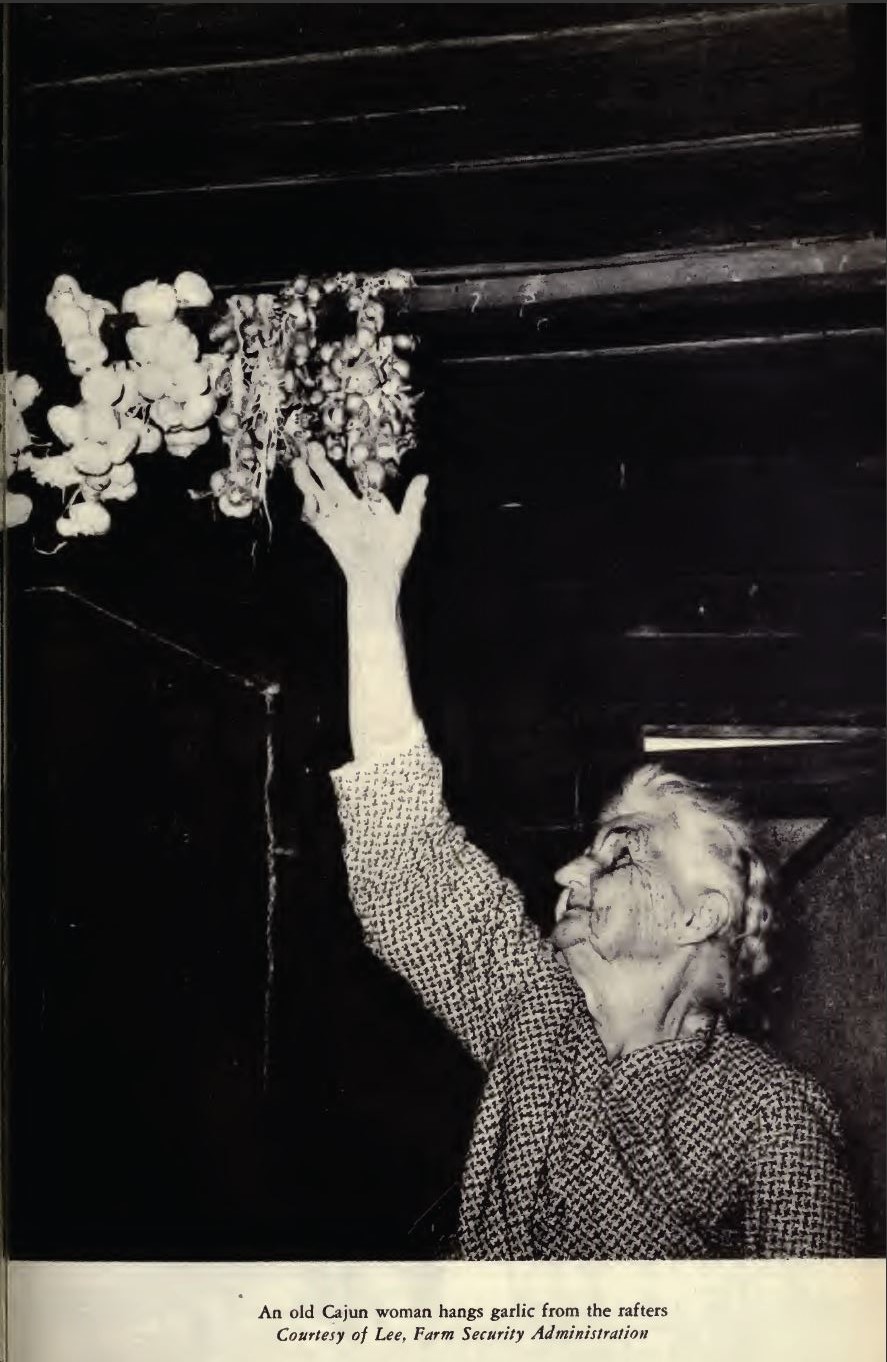

- Old Cajun Woman

- Shrimp Fleet Waiting To Be Blessed

- The Archbishop on the Way To Bless the Shrimp Fleet

BETWEEN PAGE 246 AND PAGE 247

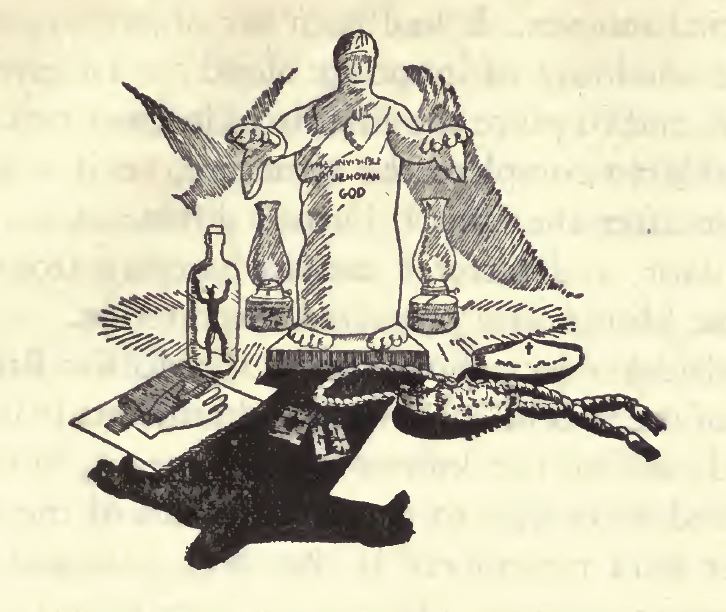

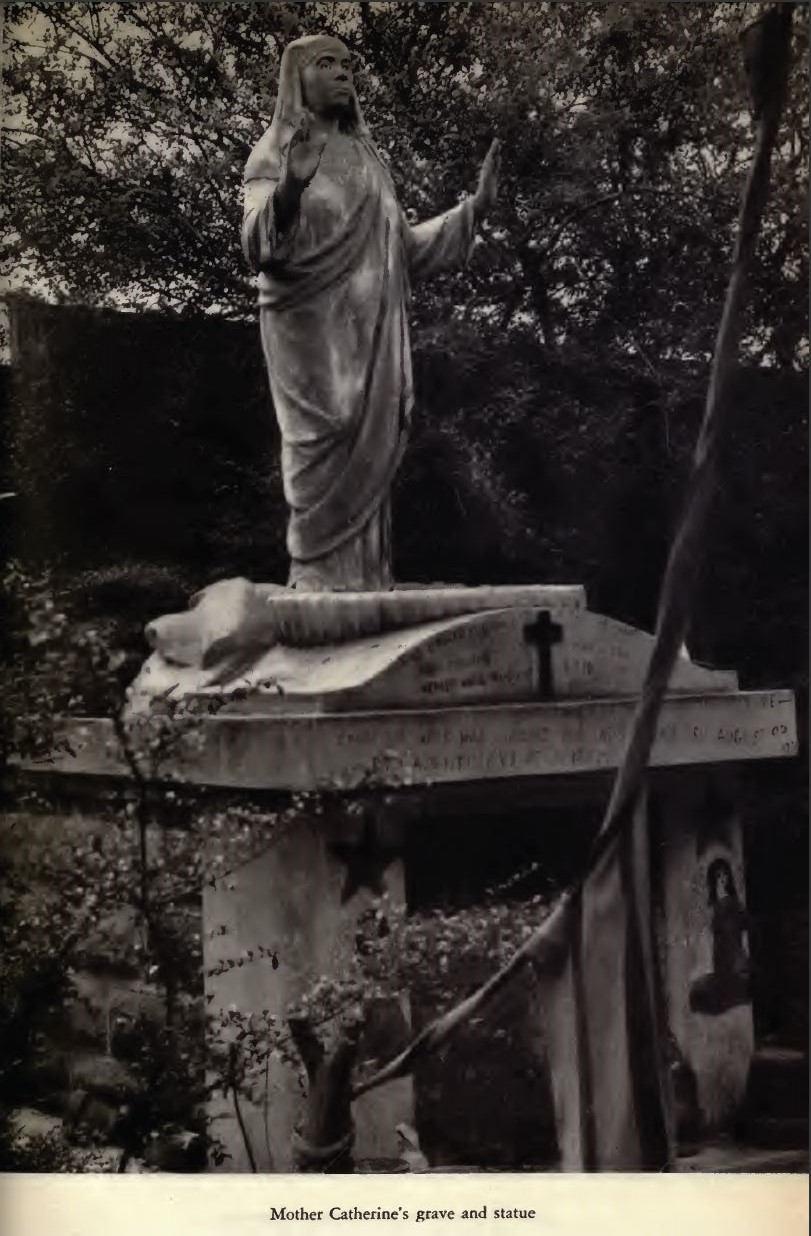

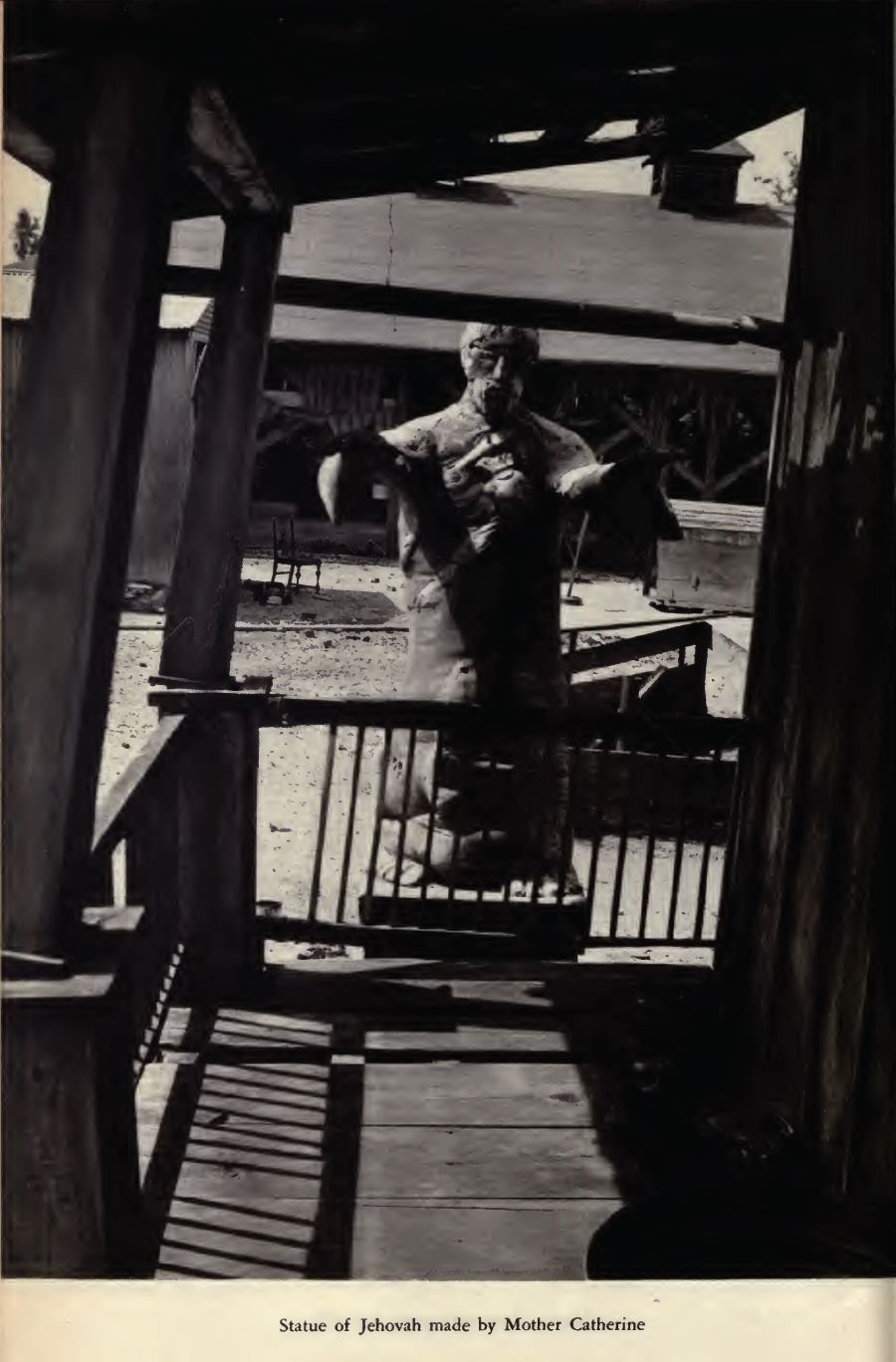

- Statue of Mother Catherine Mother Catherine’s Statue of Jehovah

- Mother Maude Shannon, Leader of a Popular Cult of Today

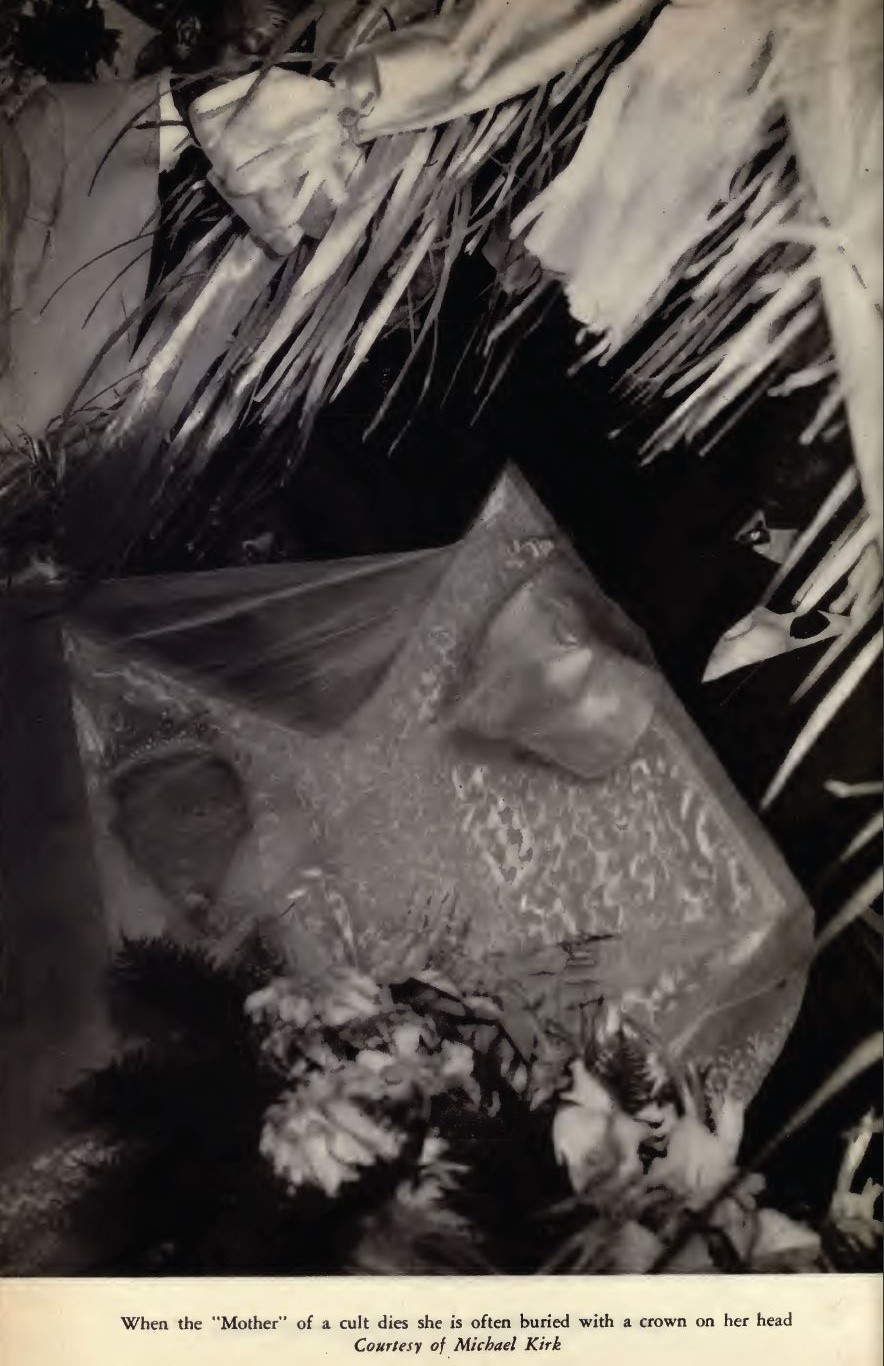

- When the ‘Mother’ of a Cult Dies She Is Often Buried with a Crown on her Head

BETWEEN PAGE 278 AND PAGE 279

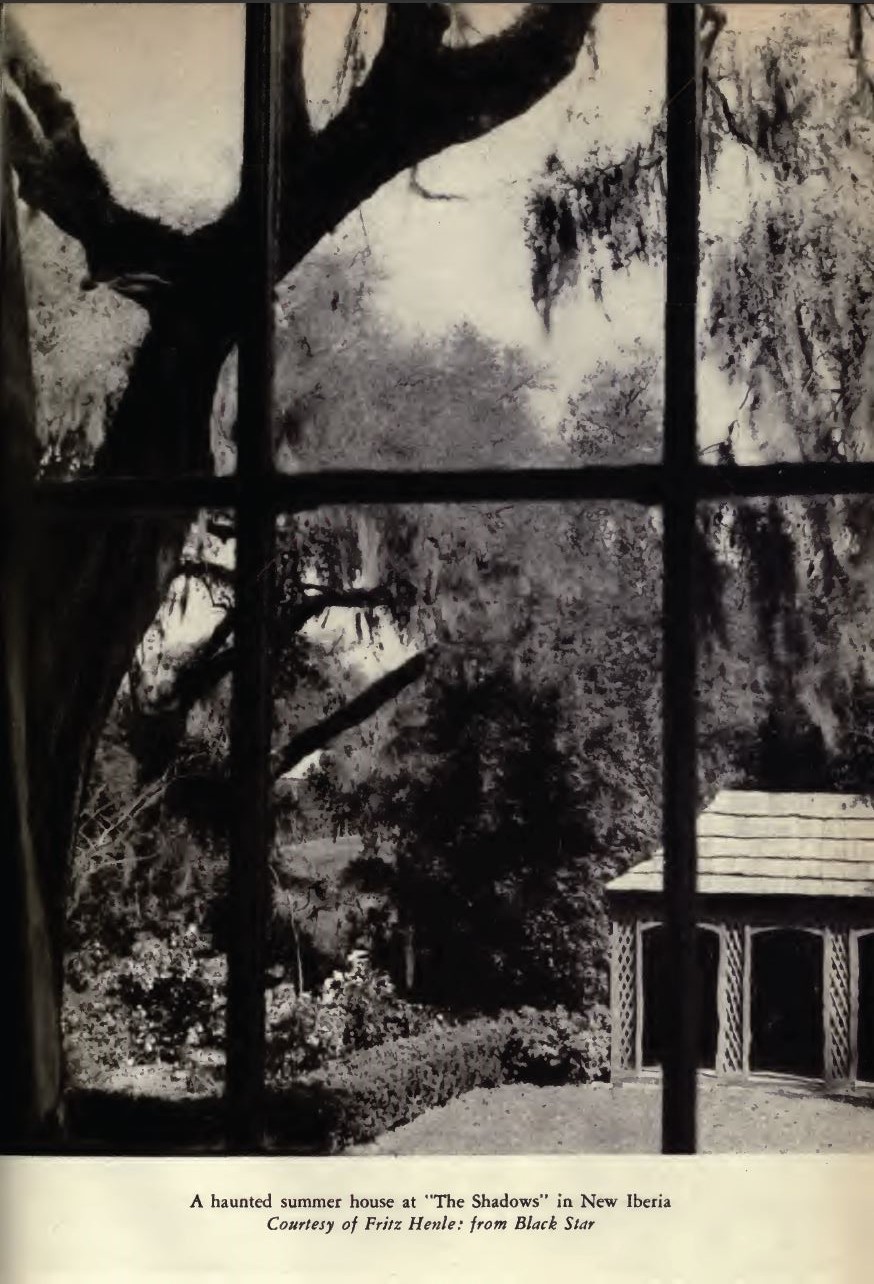

- A Haunted Summer House at ‘The Shadows’ in New Iberia

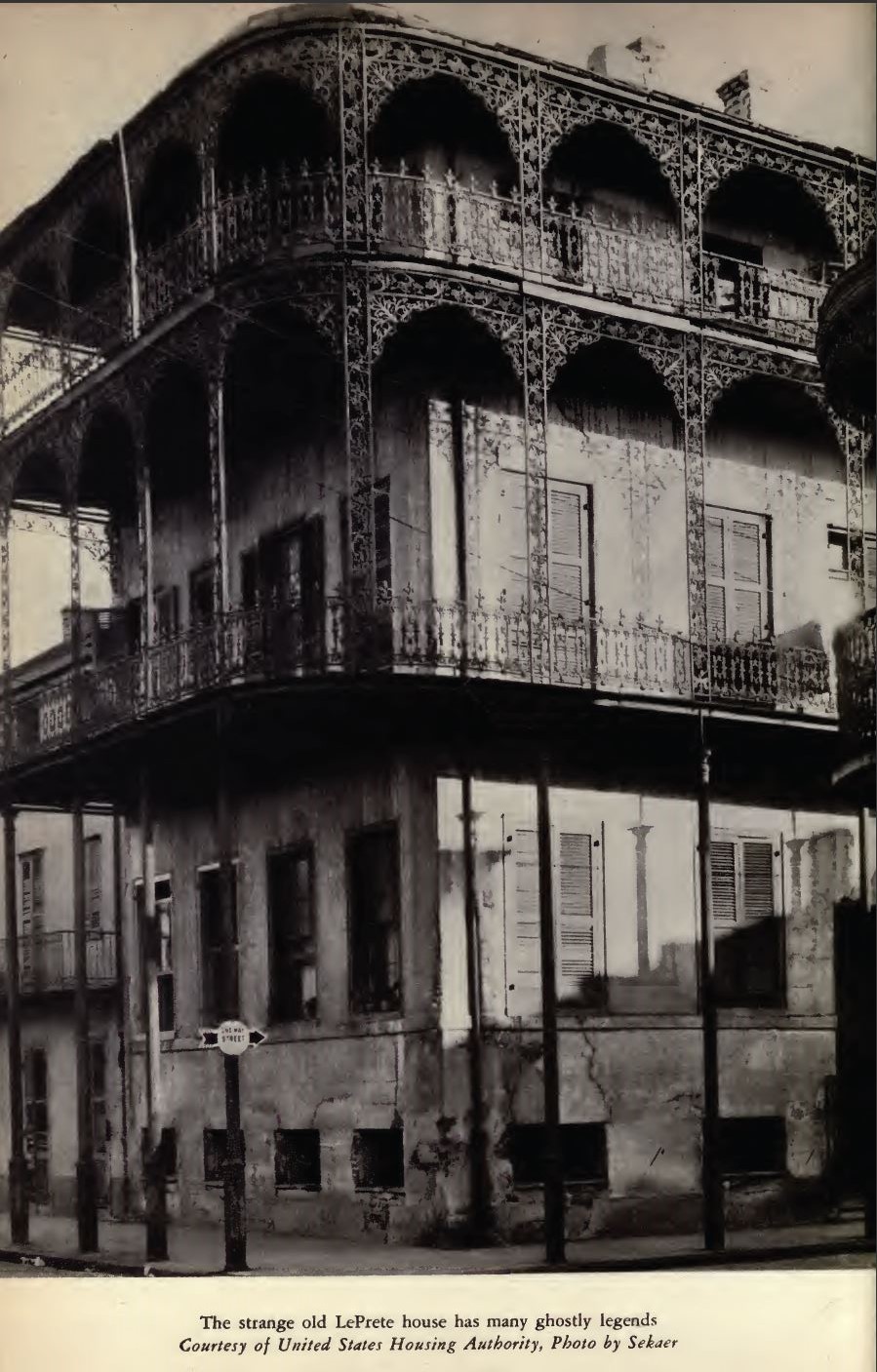

- The Strange Old LePrete House Has Many Ghostly Legends

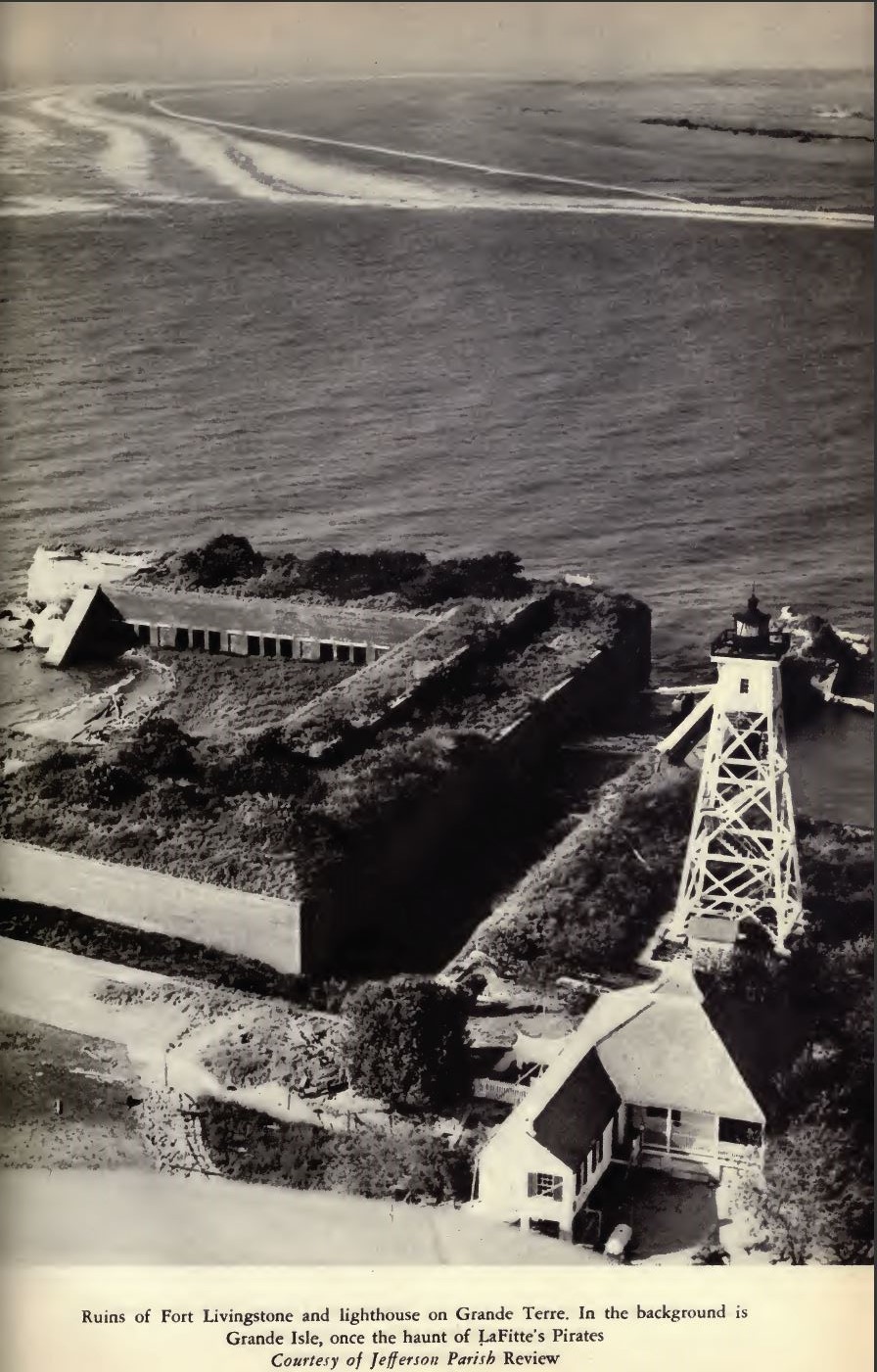

- Fort Livingstone and Grande Isle, Once the Haunt of Lafitte’s Pirates

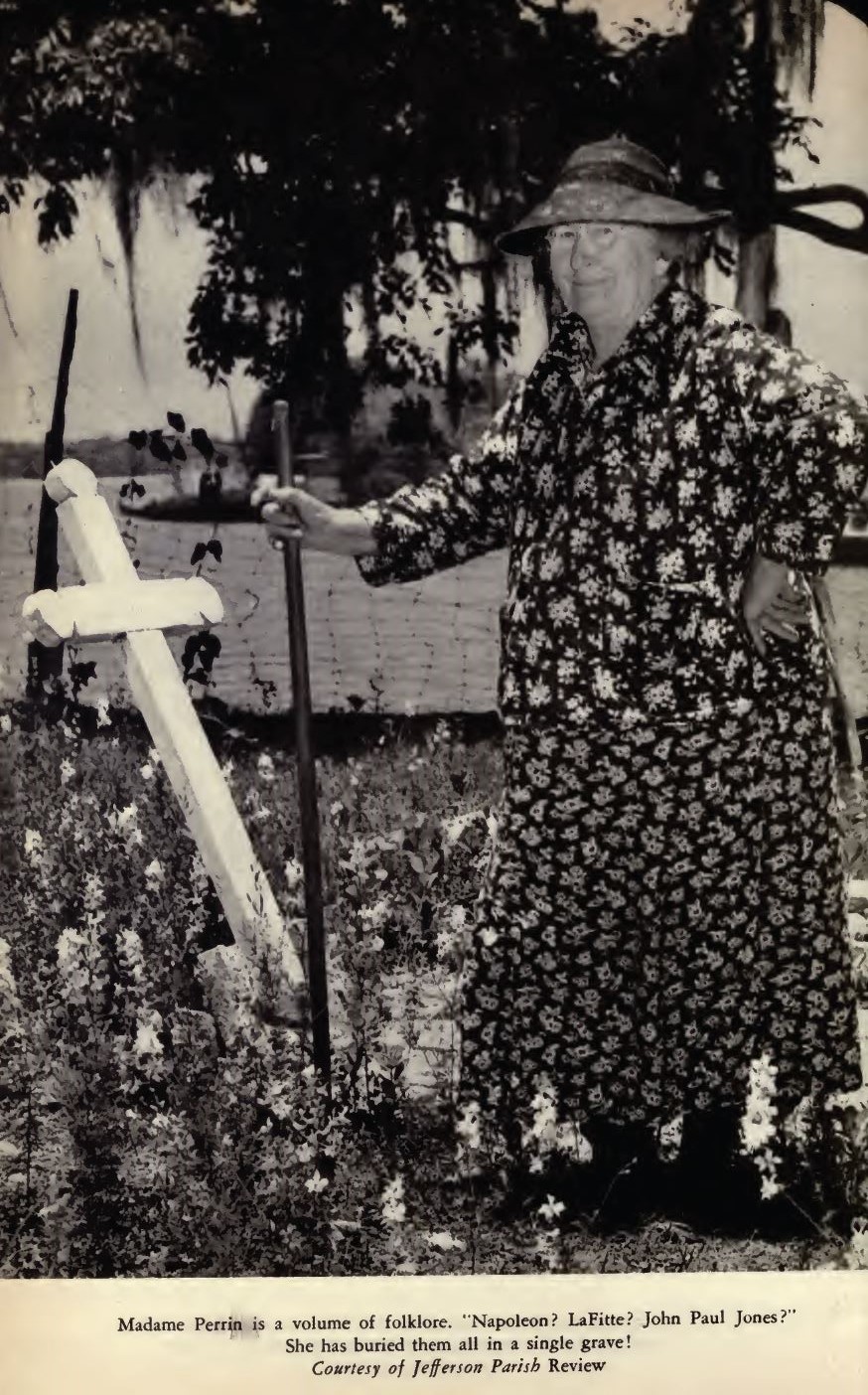

- Madame Perrin Who Claims That Napoleon, John Paul Jones and Pirate

- Lafitte Are Buried in the Same Grave

BETWEEN PAGE 342 AND PAGE 343

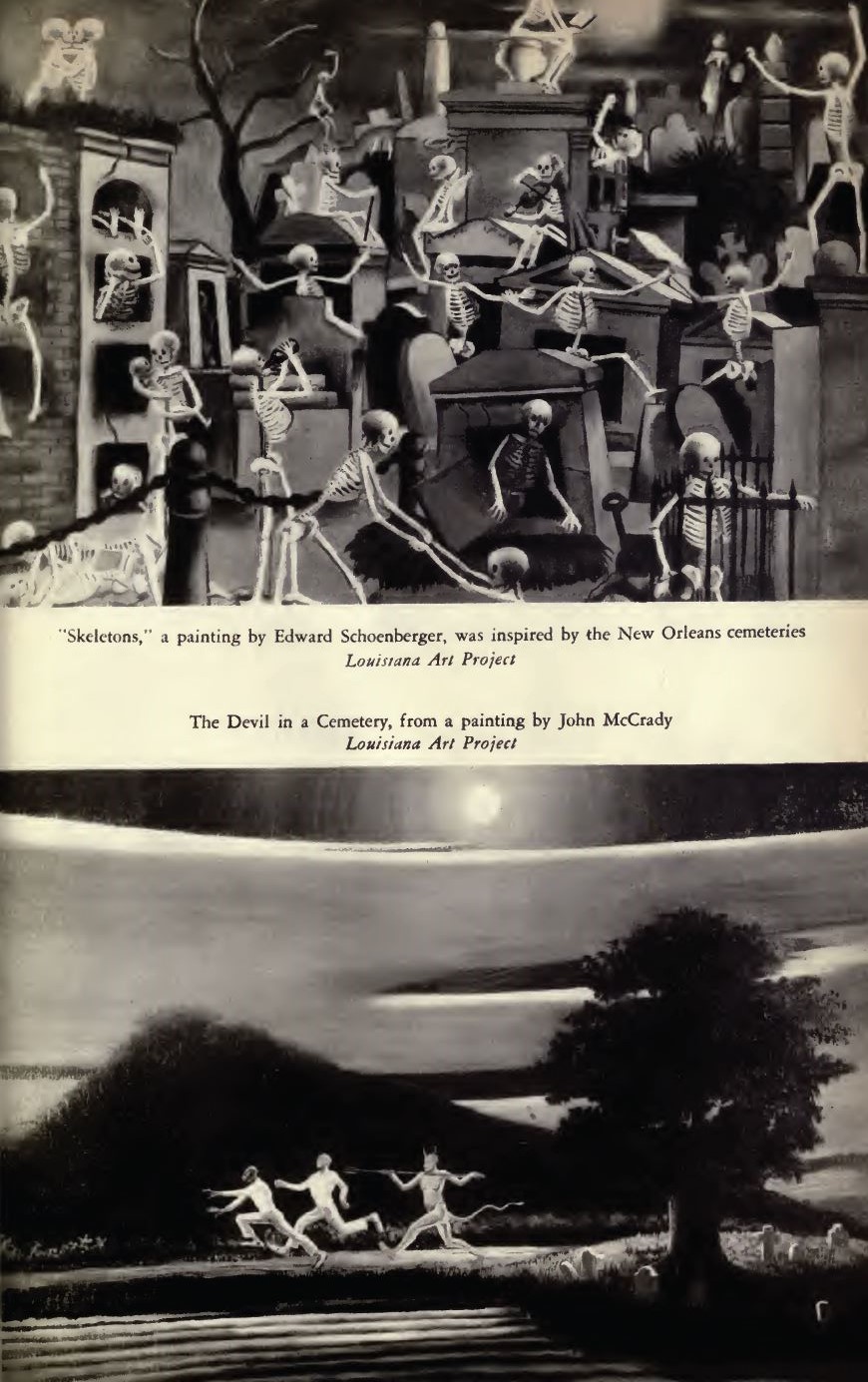

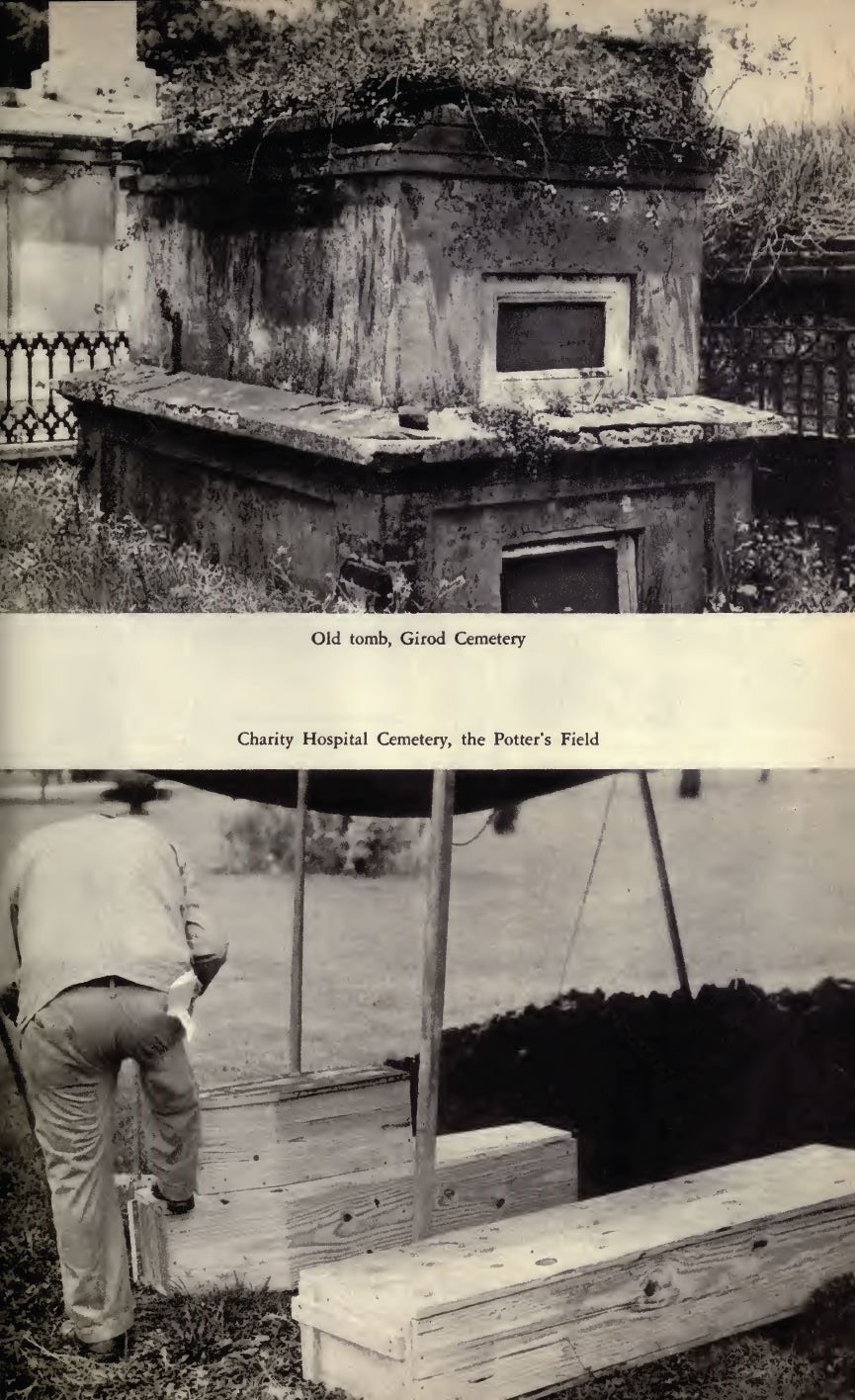

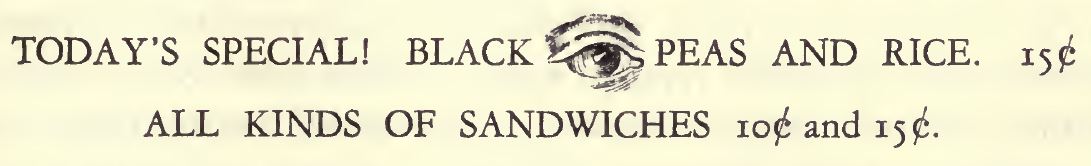

- ‘Skeletons,’ a Painting by Edward Schoenberger, Inspired by

- New Orleans Cemeteries

- ‘The Devil in a Cemetery,’ Painting by John McCrady The Mausoleum of Michael the Archangel

- Old Tomb, Girod Cemetery

- Charity Hospital Cemetery, the Potter’s Field

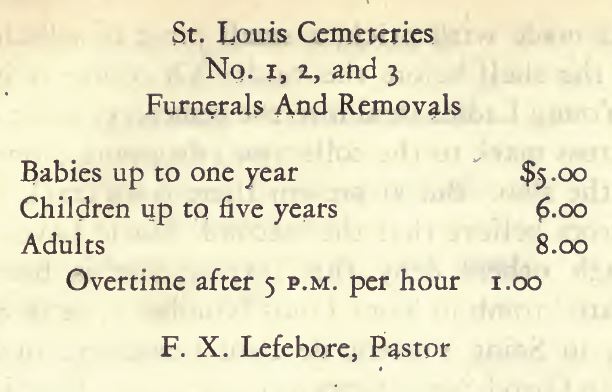

- St. Louis Cemeteries List Burial Prices

BETWEEN PAGE 406 AND PAGE 407

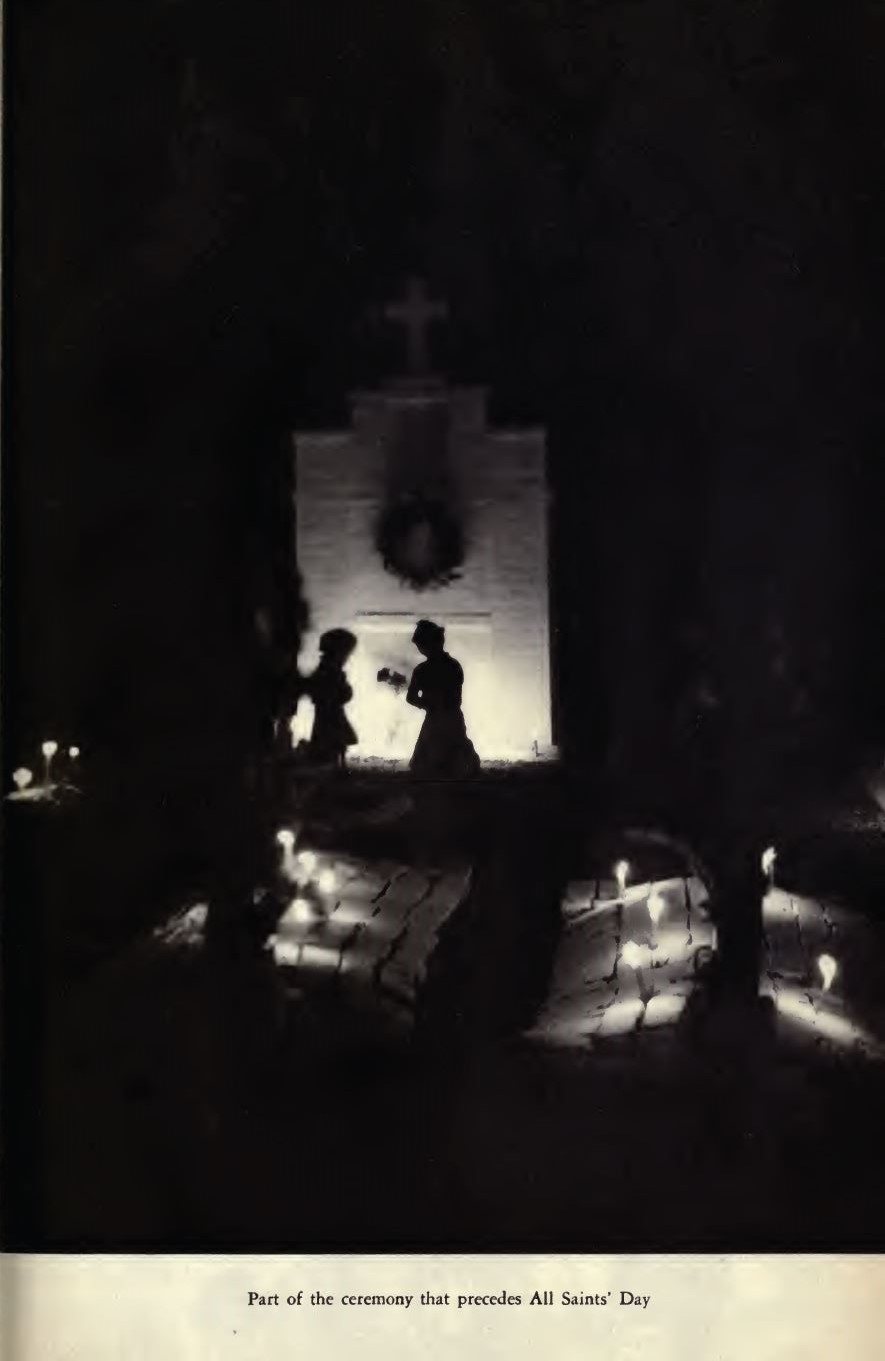

- Part of the Ceremony That Precedes All Saints’ Day

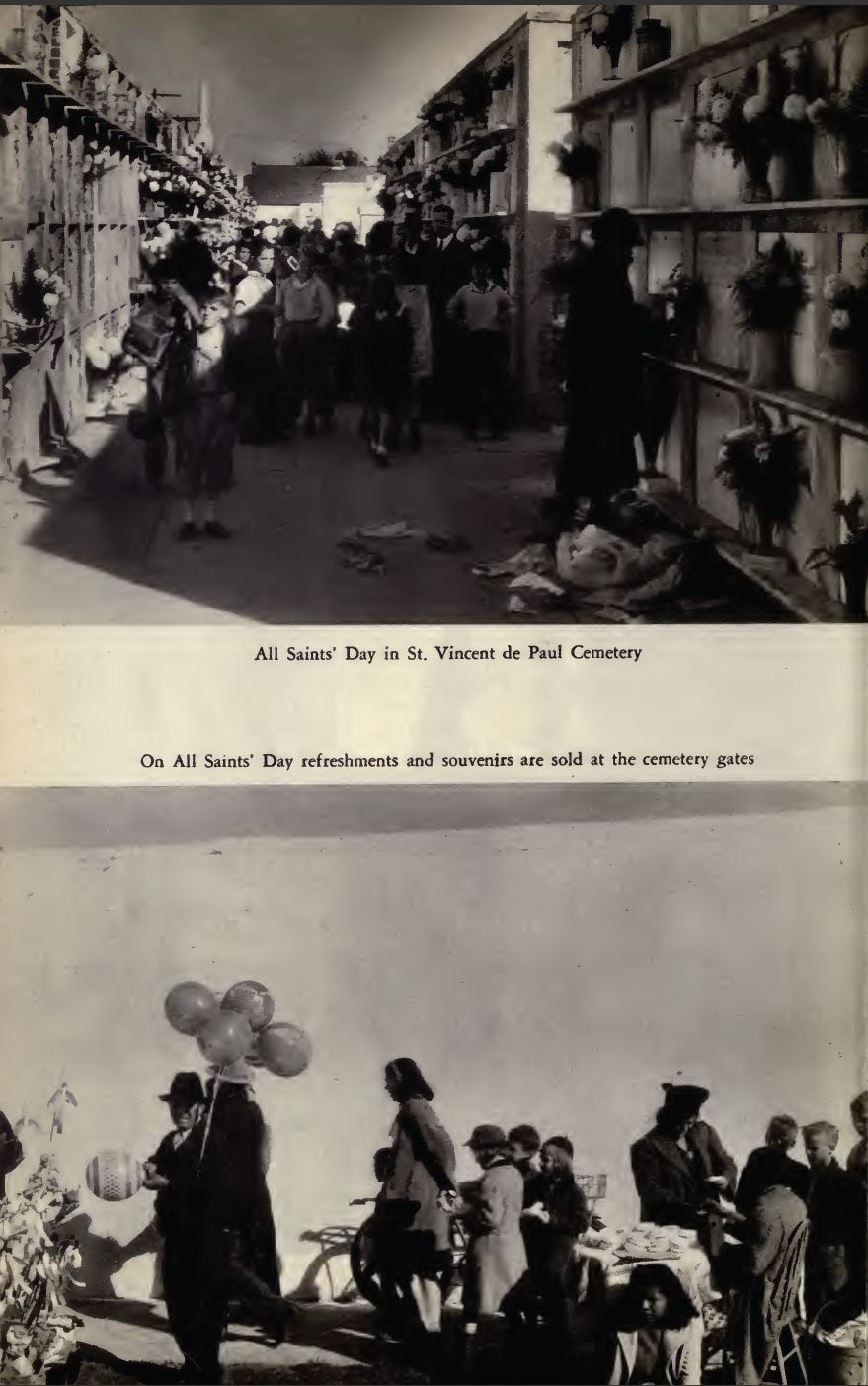

- All Saints’ Day in St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery On All Saints’ Day Refreshments and Souvenirs Are Sold at the

- Cemetery Gates

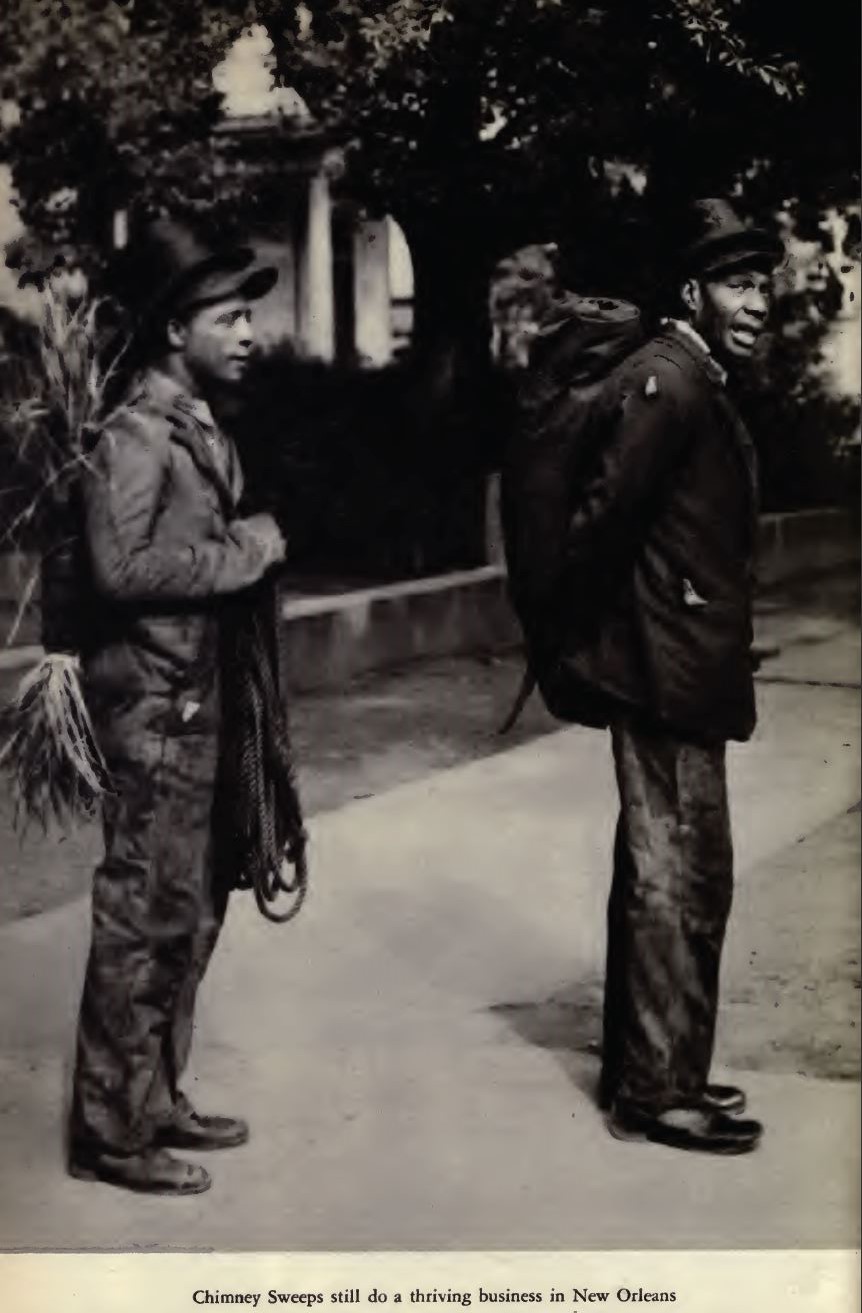

- ‘Banjo Annie,’ One of the Gayer Characters of the Vieux Carré New Orleans Chimney Sweeps

Chapter 1

Kings, Baby Dolls, Zulus, and Queens

Every night is like Saturday night in Perdido Street, wild and fast and hot with sin. But the night before Mardi Gras blazed to a new height.

The darkness outside the bars was broken only by yellow rectangles of light, spreading over the banquette, then quickly vanishing, each time saloon doors opened and closed. Music boxes blasted from every lighted doorway. Black men swaggered or staggered past, hats and caps pulled low over their eyes, which meant they were tough, or set rakishly over one ear, which meant they were sports. There were the smells: stale wine and beer, whiskey, urine, perfume, sweating armpits.

In one dimly lighted place couples milled about the floor, hugging each other tightly, going through sensuous motions to the music. Drug addicts, prostitutes, beggars and workingmen, they were having themselves a time. A fat girl danced alone, snapping her fingers.

Young black women tried to interest men, who sagged over the bars, their eyelids heavy from liquor and ‘reefers.’ One woman screamed above the din: ‘I’ll do it for twenty cents, Hot Papa. I can’t dance with no dry throat. I wants twenty cents to buy me some wine.’ She did a little trucking step, raised her dress, ‘showed her linen.’

Harry entered. Somebody shouted: ‘Shut off that damn music box. Come on, Harry. Put it on, son!’

Harry, a lean brown boy in a red silk shirt and green trousers, held a tambourine high, beat out an infectious tom-tom tempo with one fist, huskily sang words that had no meaning, but in a rhythm that was a drug. His greasy cap low over one ear, thick lips drawn back from large white teeth, he performed a wild dance, shoulders hunched, scrawny hips undulating.

Hock-a-lee-hock-a-lee-weeooo!

Wa-le-he-hela-wa-le-he-weeoo-oo!

There were comments. ‘Man, those Indians gonna step high tomorrow.’ Harry’s chant was one of the Indians’ songs.

A small girl shoved her way through the crowd around the singer. ‘Wait’ll you see us Baby Dolls tomorrow,’ she promised. ‘Is we gonna wiggle our tails!’ A man threw an arm around her neck, drew her away, over to where they could do some ‘corner loving.’

In the back room was the real man of the night. His face a trifle blank from whiskey, his eyes sleepy, King Zulu held court. This was his royal reception. Just now the King was pretty tired. The Queen rose suddenly and moved away from the table, her hips shaking angrily. If the old fool wants to go to sleep, let him. She’ll find herself somebody who can keep his eyes open and likes some fun. She’s a queen, and a queen has to have her fun.

Nobody ever goes to bed on this night. Ain’t tomorrow the big day? Not until morning do they ever go home, and then only to array themselves in costumed splendor.

But there is never any weariness about King Zulu on Carnival Day. With his royal raiment, he magically dons fresh energy. A few shots of whiskey and the trick is done. His head is up, his posture majestic — at least in the beginning of the day. Later he may droop a bit.

Strongarmed bodyguards and shiny black limousines, rented from the Geddes and Moss Undertakers, always accompany him to the Royal Barge at the New Basin Canal and South Carrollton Avenue. Cannons are fired, automobile horns blast, throats grow hoarse acclaiming him. Many a white face laughs upward from the sea of black ones, strayed far from the celebration just-coming to life down on Canal Street.

There was suspense this morning. Impatient waiting. At last, about nine o’clock, a tugboat pushed the Royal Barge, away from its resting place. Whistles shrieked. The horns and the applause of the admiring throng increased. The King took a swig from a bottle, yelled to one of his assistants, ‘Listen, you black bastard, you can help me all you want, but don’t mess ’round with my whiskey.’ Then he turned and bowed graciously toward the shore.

The other Zulus helped His Majesty greet the crowds.

‘Hello, Pete. We is in our glory today.’

‘What you say, black gal.’

‘Ain’t it fine?’

Never have any of the Zulus been highhat. Ed Hill, one of the organization’s overlords, said: ‘See Zulu people? There is the friendliest people you can find. They ain’t no stuffed shirts.’

The Zulus emerged as a Mardi Gras organization in 1910, marching on foot, a jubilee-singing quartet in front, another quartet in the rear Birth had come the year before, when fifty Negroes gathered in a woodshed. William Story was the first king, wearing a lard-can crown and carrying a banana-stalk scepter. By 1913 progress had reached the point where King Peter Williams wore a starched white suit, an onion stickpin, and carried a loaf of Italian bread as a scepter. In 1914 King Henry rode in a buggy and from that year they grew increasingly ambitious, boasting three floats in 1940, entitled respectively, ‘The Pink Elephant,’ on which rode the king and his escort, ‘Hunting the Pink Elephant,’ and ‘Capturing the Pink Elephant.’

It was in 1922 that the first yacht — the Royal Barge — was rented, and since then the ruler of the darker side of the Carnival has always ridden in high style down the New Basin Canal.

Clouds hung low this Mardi Gras Day of 1940. King Zulu and his dukes sniffed heavenward. Let it rain. Little old water never hurt a mighty Zulu. White-painted lips never lost their grins.

At Hagan Avenue the floats and supply of coconuts awaited them. With all the dignity he could summon, King Zulu mounted his ‘Pink Elephant,’ and the others clambered aboard theirs. Carefully, His Majesty arranged his red-velvet-and-ermine costume. Then a signal, and the parade was on.

Out Poydras Street to Carondelet they rolled, the thirteen-piece band swinging out with ‘I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead, You Rascal, You,’ in torrid style, sixteen black ‘policemen’ leading behind the long-legged Grand Marshal, who slung his body about and around like a drum major. The music was so hot the King started doing his number.

Onlookers leaped into the street, shouting, ‘Do it, boy, King Zulu is got his day.’

Once specially appointed black ‘Mayor’ Fisher, president of the club, shouted: ‘Doesn’t you all know we is on our way to see the white mayor? Let’s make time.’

And time was made. Hot feet hit the street. More viewers joined the parade and danced up a breeze. The maskers on the floats slung coconuts like baseballs, right into the midst of their admirers.

Once the perspiring monarch uncrowned himself. Prince Alonzo Butler was shocked. ‘King, is you a fool or not? Don’t you know a king must stay crowned?’

This particular king wasn’t really supposed to be king at all, and he felt mighty lucky about it. Johnny Metoyer was to have been the 1940 ruler, but Johnny had died months before. An ‘evil stroke’ had hit Johnny suddenly the November before and within a few days Johnny was gone. This parade was partly in celebration of his memory.

‘Them niggers is going to put it on rough for ole John,’ Charlie Fisher had vowed. ‘There ain’t going to be no hurting feet and things like that, either, ’cause them niggers don’t get no hurting feet on Mardi Gras Day. No, indeed. Them feet stays hot and, boy, when they hits the pavement serenading to that swing music, you can hear ’em pop. It’s hot feet beating on the blocks.’

Manuel Bernard was the 1940 King Zulu and he was a born New Orleans boy. Other days he drives a truck.

Gloom was in the air before Johnny Metoyer went to glory. He had been president and dictator of the organization for twenty-nine years, but had never chosen to be king until now. And this year he had announced his intention of being king, and then resigning from the Zulu Aid and Pleasure Club. This, everyone had agreed, probably meant disbanding. It just wouldn’t be the same without ole John. Even the city officials were worrying. It seemed like the upper class of Negroes had been working on Johnny, and had at last succeeded.

The Zulus had no use for ‘stuck-up niggers.’ Their membership is derived from the humblest strata, porters, laborers, and a few who live by their wits. Professional Negroes disapprove of them, claiming they ‘carry on’ too much, and ‘do not represent any inherent trait of Negro life and character, serving only to make the Negro appear grotesque and ridiculous, since they are neither allegoric nor historical.’

When, in November, 1939, word came that Johnny Metoyer was dead, people wouldn’t believe it. The night the news came, the Perdido Street barroom was packed. Representatives of the Associated Press, the United Press and the local newspapers rubbed shoulders with Zulus, Baby Dolls and Indians. The atmosphere was deep, dark and blue. Everybody talked at once.

‘Ain’t it a shame?’

‘Poor John! He’s gotta have a helluva big funeral.’

‘Put him up right so his body can stay in peace for a long time to come.’

Somebody started playing ‘When the Saints Come Marching In,’ written by Louis ‘Satchmo’ Armstrong, Metoyer’s bosom friend. Then it is suggested that a telegram be sent to Armstrong. He’s tooting his horn at the Cotton Club on Broadway, but it is felt he’ll board a plane and fly down for the funeral.

A doubt was voiced that any Christian church would accept the body for last rites. ‘John was a man of the streets, who ain’t never said how he stood on religion.’ Probably, others said confidently, if there were enough insurance money left, one of the churches could be persuaded to see things differently. Of course, he would be buried in style befitting a Zulu monarch. Members must attend in full regalia, Johnny’s body must be carried through headquarters, there must be plenty of music, coconuts on his grave. Maybe Mayor Maestri could be persuaded to proclaim the day a holiday in Zululand.

But Johnny had a sister; Victoria Russell appeared on the scene and put down a heavy and firm foot. All attempts to make the wake colorful were foiled. ‘Ain’t nobody gonna make a clown’s house out of my house,’ said Sister Victoria Russell.

Even the funeral — held on a Sunday afternoon, amid flowers and fanfare and a crowd of six thousand — was filled with disappointments. Louie Armstrong had not been able to make the trip down from New York. Sister Russell banned the coconuts and the Zulu costumes.

At the Mount Zion Baptist Church Reverend Duncan mumbled his prayers in a whisper, peeping into the gray plush casket every now and then. He opened with a reprimand. ‘Does you all know this is a funeral, not a fun-making feast?’

A drunken woman in the church yelled: ‘I knows. It brings a pitiful home.’

Reverend Duncan went on, while pallbearers raised Zulu banners. ‘In the midst of life we is in death.’

The congregation sang, ‘How Sweet Is Jesus!’

Reverend Horace Nash knelt and prayed: ‘Lawd, look at us. Keep the spirit alive that makes us bow down before you. Keep our hearts beating and our souls ever trustful today and tomorrow.’

Somebody shouted, ‘Don’t break down, brother.’

Outside waited a fourteen-piece brass band and eighteen automobiles. Thousands marched on foot. The band struck up ‘Flee as a Bird,’ and the cortege was on its way toward Mount Olivet Cemetery. Everyone was very solemn, and there was not a smile visible. All Zulus wore black banners draped across their chests and their shoulders.

Then, after the hearse had vanished into the cemetery, the entire aspect of the marchers changed. The band went into ‘Beer Barrel Polka,’ and dancing hit the streets. Promenading in Mardi Gras fashion lasted two hours, ending in Metoyer’s own place of business, where the last liquor was purchased and consumed. Sister Russell, returning to the scene, then ordered all Zulus out.

Later a meeting was called in Johnny Metoyer’s bedroom. His belongings had been removed, but his razor strop still dangled on one wall. A member, gazing at this sadly, remarked, ‘John was the shavingest man you wanted to see.’

At eight-thirty Reverend Foster Sair opened with a prayer.

‘Lawd, we is back within the fold of the man who caused us to be. We is sittin’ here in his domicile. Help us never to forget John L. Metoyer. Let us carry on the spirit of our founder. O Lawd, preserve our club. Make it bigger and better. Let no evil creep into it. Amen.’

Inspired by this, it was immediately decided that the Zulus would ‘carry on,’ that there would be a parade this year, anyway. Then Vice-President Charlie Fisher announced he was stepping into the presidency, and that all other officers would advance in office in proper order.

Definite insults followed from those who disapproved.

‘Shut up!’ someone admonished them. ‘You is talkin’ about the President now.’

There was more argument and bickering in the meetings that followed. Manuel Bernard, friend of Fisher, was at last chosen to be the 1940 king. At this meeting the music box in the front bar wailed forth with ‘The Good Morning Blues,’ and dancers were kicking and stomping, twisting their supple bodies the way they felt. It disturbed the meeting a little, but someone said: ‘Let the music play, ’cause the mournin’ is over. We is all gotta do some flippin’ around now.’

So the Zulus didn’t fade out after all, but marched in high style in 1940, and Manuel Bernard, rocking back and forth on the high throne of his float, was a proud and happy man.

Finally the parade reached the City Hall and paused before the crowded stand. The white mayor wasn’t present, but a representative received coconuts and a bow from His Majesty. The band played ‘Every Man a King,’ Huey P. Long’s song, and the dancing was wild. It was King Zulu’s day.

The next long stop was at Dryades and Poydras Streets. A proprietor of a beer parlor at that intersection presented the King with a silver loving cup containing champagne.

‘Damn, that’s good,’ said His Majesty, and smacked his lips.

A bevy of short-skirted black girls invited him down just then, but no dice. ‘Ain’t no funny crap today. Remember last year?’ Last year King Zulu left his float to follow a woman and held up the parade for two hours. So these girls, whom the boys call the ‘zig-a-boos,’ disappointedly went their way.

Strange things happen even to a king. It suddenly went down the line, ‘The King has done wet himself.’ Didn’t make much difference, though. He had spilled so much whiskey on his costume, nobody could tell what was what.

Everybody was a little drunk now. The grass hula skirts all Zulus wear over long white drawers swished faster and faster as the maskers on the floats ‘put it on,’ and the nappy black skull caps adorning their heads were set at dashing angles. The parade moved swifter now toward the Geddes and Moss Undertaking Parlors, where the Queen and her court awaited them on a balcony over the street.

A thunderous ovation greeted King Zulu at South Rampart and Erato Streets. A high yellow gal fanned her hips by him and he temporarily deserted his float. ‘Mayor’ Fisher hauled him back to the dignity and comparative safety of his high perch atop the float. ‘I never thought this could happen to a king,’ His Majesty sighed. Pretty girls like that wouldn’t want the King when he was ‘jest a man.’

‘It’s damn funny,’ Fisher sniffed, ‘how womens is. Now that woman knows the King is busy, still she wants him. Every time I think how much trouble Zulus give me I get mad.’

All over South Rampart Street women were jumping up and down and feeling hot for the King. The musicians were wet with perspiration and from the showers that had fallen during the morning, but they kept beating out the music and getting hotter all the time.

After knocking out several numbers, the entire band filed into a saloon for drinks, and when they came out everybody started ‘kicking ’em up.’ The dances grew more violent. Women lowered their posteriors to the ground, shaking them wildly as they rose and fell, rolled their stomachs, vibrated their breasts. A crowd of Baby Dolls came along, all dressed up in tight, scanty trunks, silk blouses and poke bonnets with ribbons tied under dusky chins. False curls framed faces that were heavily powdered and rouged over black and chocolate skins. The costumes were of every color in the rainbow and some that are not. They joined the crowd, dancing and shaking themselves.

‘Sure, they call me Baby Doll,’ said one of them, who was over six feet tall and weighed more than two hundred pounds. ‘That’s my name.

‘I’m a Baby Doll today and every day. I bin a Baby Doll for twenty years. Since I always dressed like a Baby Doll on Mardi Gras the other girls said they would dress like me; they would wear tight skirts and bloomers and a rimmed hat. They always say you get more business on Mardi Gras than any other day, so I had a hard time making them gals close up and hit the streets. See, mens have fun on Carnival. They come into the houses masked and want everything and will do anything. They say, “I’m a masker, fix me up.” Well, them gals had a time on Mardi Gras, havin’ their kicks.

‘The way we used to kick ’em up that day was a damn shame. Some of the gals didn’t wear much clothes and used to show themselves out loud. Fellows used to run ’em down with dollar bills in their hands, and you didn’t catch none of them gals refusing dollar bills. That’s why all the women back Perdido Street wanted to-be Baby Dolls.

‘We sure did shine. We used to sing, clap our hands, and you know what “raddy” is? Well, that’s the way we used to walk down the street. People used to say, “Here comes the babies, but where’s the dolls?”

‘I’m the oldest livin’ Baby Doll, and I’m one bitch who is glad she knows right from wrong. But I do a lot of wrong, because I figures wrong makes you as happy as right. Don’t it?

‘Sure, I tried religion, but religion don’t give you no kicks. Just trouble and worry.

‘Say what you like, it’s my business. I’ll tell anybody I sells myself enough on Mardi Gras to do myself some good the whole year around. There ain’t no sense in being a Baby Doll for one day only. Me, I’m a Baby Doll all the time.

‘Just follow a Baby Doll on Mardi Gras and see where you land. You know, if you follow her once, you’ll be following her all the time. That’s the truth.

‘I ain’t no trouble-seeker, but I got plenty trouble. The other day a man come into my house with fifty cents, but a dime short. I just picked up a chair and busted it over his head. That nigger is always comin’ in short. He punched me in the nose, and we went to jail. The judge turned me loose, but he says, “Gal, don’t you come back here no more.” And I says, “No, sir, Judge.” When I stabbed Uncle Dick the next day they give me three months. But Dago Tony got me out.

‘I didn’t want to cut Uncle Dick, but he kept messin’ around. I sure don’t like nobody to mess around with me. I just can’t stand it.’

Baby Doll has been living with Uncle Dick for five years now. She beats him up regularly. She has stabbed him and hit him over the head with rocking chairs, bricks, and sticks. Uncle Dick is a retired burglar and ‘switch-blade wielder’; that is, he used a knife that opened when he pressed a button and he could ‘kill a man dead’ in a split second. But things got too hot. Now it is whispered he is a stool pigeon for the police in the crime-infested neighborhood where he lives.

He depends on Baby Doll, but she’s a tough number. Besides her profession, she curses a blue streak, uses dope, is a stickup artist, smokes cigars and packs a Joe Louis wallop.

‘Dago Tony has been around himself,’ Baby Doll went on. ‘He is all right. Me and him done pulled plenty lemons together. He got the peelin’ and I got the juice.’

A ‘lemon’ is a method of extracting a man’s bankroll when he is busy with a woman.

‘Dago Tony got me into a business once that was too hot to keep up, but, man, was it solid! He’d give the drunks a big hooker with knockout drops in their glass, and when they passed out I was on ‘em. The trouble was I had to hit too many of them niggers over their heads. They’d wake up too quick. I seen so much blood drippin’ from people’s heads I got scared and cut that stuff out. I’ll tell you, a Baby Doll’s life ain’t no bed of roses.’

Baby Doll began to think she had talked too much. Other things began to creep into her mind, too. Some young black men edging the crowd were giving her the once-over, and business is business.

‘You’re holdin’ me up. I got to hit the streets. There’s more money for me in the streets than there is here. Maybe I’m missin’ a few tricks.’ And she was off through the crowd around the floats, walking ‘raddy’ to attract attention.

‘I was the first Baby Doll,’ Beatrice Hill asserted firmly, when questioned about the history of the organization. ‘Liberty and Perdido Streets were red hot back in 1912, when that idea started. Women danced on bars with green money in their stockings, and sometimes they danced naked. They used to lie on the floor and shake their bellies while the mens fed them candy. You didn’t need no system to work uptown. It wasn’t like the downtown red-light district, where they made more money, but paid more graft. You had to put on the ritz downtown, which some of the gals didn’t like. You did what you wanted uptown.’

Uptown prostitutes got high on marijuana and ‘snow.’ They still do. Beatrice is fifty-two and is about beat out now. Her arms and legs are thickly spotted with black needle holes. She still uses drugs, and admits it. Also, she goes to Charity Hospital and takes treatment for syphilis. Back in 1912, she made fifty to seventy-five dollars a day hustling and stealing. Her man, Jelly Beans, got most of it, and they blew the rest ‘gettin’ their kicks.’ Beatrice is all bad and proud of it. She’s been to jail for murder, shooting, stealing, and prostitution. She boasts of her hectic past with gusto and vanity.

‘Them downtown bitches thought their behinds was solid silver,’ she recalls contemptuously, ‘but they didn’t never have any more money than we did. We was just as good lookers and had just as much money. Me, I was workin’ right there on Gravier and Franklin Streets.

‘We gals around my house got along fine. Them downtown gals tried to get the police to go up on our graft, but they wouldn’t do it. Does you remember Clara Clay, who had all them houses downtown? Well, we was makin’ good money and used to buy up some fun. All of us uptown had nothin’ but good-lookin’ men. We used to send them downtown ’round them whores and make ’em get all their money until they found out and had ’em beat up. Then we stopped. I’m tellin’ you that was a war worse’n the Civil War. All the time we was tryin’ to outdo them downtown gals.

‘I knew a lady, name was Peggy Bry; she used to live at 231 Basin Street. Well, anyhow, Miss Bry gave a ball for the nigger bitches in the downtown district at the Entertainers’ Café, and she said she didn’t want no uptown whore there. All them gals was dressed to kill in silks and satins and they had all their mens dressed up, too. That was goin’ to be some ball. We heared about it long before. So, we figures and figures how we could go and show them whores up with our frocks. I told all my friends to get their clothes ready and to dress up their mens, ’cause we was goin’ to that ball.

‘Everybody got to gettin’ ready, buyin’ up some clothes. Sam Bonart was askin’ the mens what was the matter and Canal Street was lookin’ up at us niggers like we was the moon. We was ready, I’m tellin’ you. I figures and figures. So, I figures what we would do. I got hold of a captain, the baddest dick on the force, and I tells him what was what. I tells him a white whore is givin’ a ball for niggers and didn’t want us to come. He says, “Is it a public hall?” And I says it is. He tells us to get ready to do our stuff and go to that ball. You see, the Captain knows we is in a war with them downtown bitches. Me, I figures he was kiddin’, so I went to him and told him if he’d come downtown with us I’d give him a hundred dollars. He says, sure he would.

‘Child, we got the news around for the gals to get ready. And was they ready! Is the sun shinin’? It was a Monday night and Louie Armstrong and his Hot Five and Buddy Petit was gonna be playin’ at that ball. We called up Geddes and Moss and hired black limousines. You know them whores was livin’ their lives! All the houses was shut down, and the Captain was out there in front. I’m tellin’ you when that uptown brigade rode up to the Entertainers’ Café, all the bitches came runnin’ out. Then they saw the Captain and they all started runnin’ back inside. We just strutted up and filed in and filled the joint. I’m tellin’ you, that was somethin’!

‘The first thing I did was to order one hundred and four dollars’ worth of champagne, and the house couldn’t fill the order. The bartender said, “You got me.” I took all the place had, and the band starts playin’ “Shake That Thing,” and dedicates it to me. This white bitch, Miss Bry, comes runnin’ up to me and says, “Look here, this is my party for my friends.” I says: “Miss Bry, I’m the one showed you how to put silk teddies on your tail. Who is you? What’s your racket?” Then the Captain walks up, lookin’ hard, and he says: “Miss Bry, you ain’t got no right in this public dance. If you don’t shut your trap, I’ll pull you in.” Man, would you keep quiet? Well, that’s what she did.

‘One of my gals — I think it was Julia Ford — got up on a table and started shakin’ it on down. We took off all her clothes, and the owner of the place started chargin’ admission to come in to the dance. Miss Bry raised particular hell about this, then went on home. We broke up that joint for true. The Entertainers ain’t never seen a party like that one.

‘Let me tell you, and this ain’t no lie: Every girl with me had no less than one hundred dollars on her. We called that the hundred-dollar party. Say, niggers was under the tables tryin’ to find the money we was wastin’ on the floor. I remembers one nigger trying to tear my stockings open to get at my money till my man hit him over his head with a chair, and that nigger went to the hospital. ’Course it all ended in a big fight and we all went to jail.

‘It wasn’t long after that when a downtown gal named Susie Brown come to see me. She says she wants to work uptown, so we give her a chance. She got to makin’ money, and soon she was called the best-dressed gal in Gravier Street. I didn’t mind, me. She was workin’ in my house, and her bed percentage was fine. I done seen time when I made fifty dollars in a day just waitin’ for Susie to get done turnin’ tricks.

‘Shux, that wasn’t nothing. When them ships come in, that’s when I made money. All them sailors wanted a brownie. High yellows fared poorly then, unless they got in them freakish shows. When I took in fifty dollars in them days it was a bad day. I was rentin’ rooms, payin’ me a dollar every time a gal turned a trick. Then I had two gals stealin’ for me, and I was turnin’ tricks myself.

‘Lights was low around my house and some awful things was done right in the streets. The police? Shux, does you know what we was payin’ the law? Every gal paid three bucks a day and the landlady paid three and a half, but we didn’t mind at all, ’cause we made that with a smile.

‘Everywhere we went like the Silver Platter, the Elite, the Black and Tan and so on, people used to say, “Look at them whores!” We was always dressed down and carried our money in our stockings. See like around Mardi Gras Day? We used to break up the Zulu Ball with money, used to buy the King champagne by the case. That’s another thing, we had the Zulus with us. Shux, we took Mardi Gras by storm. No, we wasn’t the Baby Dolls then; I’m talkin’ about before that.

‘In 1911, Ida Jackson, Millie Barnes and Sallie Gail and a few other gals downtown was makin’ up to mask on Mardi Gras Day. No, I don’t know how they was goin’ to mask, but they was goin’ to mask. We was all sittin’ around about three o’clock in the morning in my house. A gal named Althea Brown jumps up and she says, “Let’s be ourselves. Let’s be Baby Dolls. That’s what the pimps always calls us.” We started comin’ up with the money, but Leola says: “Hold your horses. Let every tub stand on its own bottom.” That suited everybody fine and the tubs stood.

‘Everybody agreed to have fifty dollars in her stocking, and that we could see who had the most money. Somebody says, “What’s the name of this here organization?” And we decided to call ourselves the Million-Dollar Baby Dolls, and be red hot. Johnny Metoyer wanted us to come along with the Zulus, but we said nothin’ doin’. We told Johnny we was out to get some fun in our own way and we was not stoppin’ at nothin’.

‘Some of us made our dresses and some had ’em made. We was all lookin’ sharp. There was thirty of us — the best whores in town. We was all good-lookin’ and had our stuff with us. Man, I’m tellin’ you, we had money all over us, even in our bloomers, and they didn’t have no zippers.

‘And that Mardi Gras Day came and we hit the streets. I’m tellin’ you, we hit the streets lookin’ forty, fine and mellow. We got out ’bout ten o’clock. We had stacks of dollars in our stockings and in our hands. We went to the Sam Bonart playground on Rampart and Poydras and bucked against each other to see who had the most money. Leola had the most — she had one hundred and two dollars. I had ninety-six dollars and I was second, but I had more home in case I ran out. There wasn’t a woman in the bunch who had less than fifty dollars. We had all the niggers from everywhere followin’ us. They liked the way we shook our behinds and we shook ’em like we wanted to. ‘Know what? We went on downtown, and talk about puttin’ on the ritz! We showed them whores how to put it on. Boy, we was smokin’ cigars and flingin’ ten- and twenty-dollar bills through the air. Sho, we used to sing, and boy, did we shake it on down. We sang “When the Sun Goes Down” and “When the Saints Come Marchin’ Through I Want to Be in That Number.” We wore them wide hats, but they was seldom worn, ’cause when we got to heatin’ we pulled ’em off. When them Baby Dolls strutted, they strutted. We showed our linen that day, I’m tellin’ you.

‘When we hit downtown all them gals had to admit we was stuff. Man, when we started pitchin’ dollars around, we had their mens fallin’ on their faces tryin’ to get that money. And there you have the startin’ of the Baby Dolls. Yeah, peace was made. All them gals got together.’

The parade was about ready to get started again now. The King heaved a slow curve at the proprietor of the saloon and the coconut fell right smack on his head. Everybody laughed except ‘Mayor’ Fisher. It was an indication that His Majesty was drunk.

‘When the time comes,’ moaned Fisher, rolling white eyeballs around in a fat, black face, ‘that I can stop worryin’ about that King and everybody else, I’m goin’ to feel heaps better. It’s time to cut out this foolishment, anyway. We is on our way to meet the Queen.’

The band began swinging it faster, and the Zulus’ hot feet beat faster, too. Everybody was feeling fine. King Manuel stretched out his arms congenially, and kept laughing out loud, though his head was low, and the pavement looked about to jump right up and slap him in the face.

It was about one-thirty when they reached the small building, where thousands waited to see the Queen greet her lord.

The King posed for cameramen, and bowed to everybody graciously. He leaned over and accepted flowers and a ribbon key of welcome from Doctor W. A. Willis, whose wife sponsors this use of the funeral parlors every year.

Gertrude Geddes Willis made an address: ‘My powerful monarch, it is a pleasure to welcome you to Geddes and Moss Undertakers. May your every wish be granted for your subjects and yourself, and may you live forever in the splendor that fits a king.’ She handed His Majesty a bottle of champagne, ordered the waiters to bring more for the rest of the Zulus.

Then there was an awed hush as a maid led the Queen out upon the platform, and sighs passed through the dusky crowd that were a tribute to her beauty. There were gasps when it could be clearly seen that she wore an expensive-looking white satin gown, lavishly trimmed in lace, a multi-colored train of metallic cloth, a rhinestone crown, and carried accessories to match. ‘The white lady I used to work for gave me all my accessories.’ Queen Zulu revealed later. ‘She took me downtown, and she said: “Ceola, I want to fix you up right. I want you to be a damn good queen.” Those were her exact words.’

King Manuel toasted his Queen in champagne, as his float remained beneath the balcony, and she sipped some, too, -smiling down on her admiring subjects in the street below.

The ceremonies over, the court went inside for more refreshments. No one was permitted to follow them upstairs to their private quarters, where liquor of all kinds was consumed and a thousand fancy sandwiches enjoyed.

The Queen was left to have her fun, too, and she usually does very well. In fact, there’s always a certain amount of worry about letting a queen wander about during the hours between the reception and the ball to come later in the evening. It has been suggested that she be locked up during that time, but the queens have always objected strongly to that proposed measure.

The Zulus’ parade was over now, but there was always plenty going on around town. Things were really just getting warmed up.

Suddenly, this Mardi Gras afternoon, there appeared on a street corner a lone figure of an elaborately garbed Indian. He stood there, a lighted lantern in one hand, the other shading his eyes, as he peered into the street ahead, first right, then left. This Indian’s face was very black under his war paint, but his costume and feathered headdress were startlingly colorful. He studied the distance a moment, then turned and swung the lantern. Other Indians appeared, all attired in costumes at least as magnificent as the first, and in every conceivable color.

A second Indian joined the first, then a third. These three all carried lanterns like good spy boys must. Then a runner joined them, a flag boy, a trio of chiefs, a savage-looking medicine man. Beside the first or head chief was a stout woman, wearing a costume of gold and scarlet. She was the tribe’s queen, and wife of the first chief.

A consultation was held there on the corner. The chiefs got together, passed around a bottle, and argued with the medicine man until that wild creature, dressed in animal skins and a grass skirt, wearing a headdress of horns and a huge ring in his nose, jumped up and down on the pavement with rage. When, at last, it was decided that since there was no enemy tribe in sight, they might as well have a war dance, Chief ‘Happy Peanut,’ head of this tribe of the Golden Blades, emitted a bloodcurdling yell that resounded for blocks, ‘Oowa-a-awa! Ooa-a-a-awa!’

Tambourines were raised and a steady tattoo of rhythm beat out. Knees went down and up, heads swayed back and forth, feet shuffled on the pavement, as they circled round and round.

The Queen chanted this song:

Tu-way-pa-ka-way.

The Indians are comin’.

Tu-way-pa-k a-way.

The Chief is comin’.

Tu-way-pa-ka-way.

The Chief is comin’.

Tu-way-pa-ka-way.

The Queen is comin’.

Tu-way-pa-ka-way.

The Queen is comin’.

Tu-way-pa-ka-way.

The Golden Blades are comin’.

Tu-way-pa-ka-way.

The Golden Blades are comin’.

Tu-way-pa-ka-way. …

The songs the Mardi Gras Indians sing are written in choppy four-fourths time, with a tom-tom rhythm. The music is far removed from the type usually associated with Negroes. The Indians never sing a blues song, but chant with primitive and savage simplicity to this strange beat, which has an almost hypnotic effect. The beating on the tambourine and rhythmic hand-clapping are the only accompaniments to the singing. Most of the words have little meaning, though some display special interests of the tribe, such as

Tu-way-pa-ka-way.

Get out the dishes.

Tu-way-pa-ka-way.

Get out the pan.

Tu-way-pa-ka-way.

Here comes the Indian man.

Tu-way-pa-ka-way,

Tu-way-pa-ka-way.

Sometimes the chief of the tribe sings alone a boastful solo of his strength and prowess.

Tu-way-pa-ka-way.

Oowa-a-a!

Tu-way-pa-ka-way.

I’m the Big Chief!

Tu-way-pa-ka-way.

Of the strong Golden Blades.

Tu-way-pa-ka-way.

The dances are wild and abandoned. Unlike the songs, there may be detected traces of modernity, trucking and bucking and ‘messing-around’ combined with pseudo-Indian touches, much leaping into the air, accompanied by virile whooping. All this is considerably aided by the whiskey consumed while on the march, and the frequent smoking of marijuana.

The tribes include such names as the Little Red, White and Blues, the Yellow Pocahontas, the Wild Squa-tou-las, the Golden Eagles, the Creole Wild Wests, the Red Frontier Hunters, and the Golden Blades. The last numbers twenty-two members, and is the largest and oldest of those still extant.

The Golden Blades were started twenty-five years ago in a saloon. Ben Clark was the first chief and ruled until two years ago, when a younger man took over. Leon Robinson — Chief ‘Happy Peanut’ — deposed Clark in actual combat, as is the custom, ripping open Clark’s arm and gashing his forehead with a knife. That’s the way a chief is created, and that is the way his position is lost.

Contrary to the casual observer’s belief, these strangest of Mardi Gras maskers are extremely well-organized groups, whose operations are intricate and complicated.

Monthly meetings are held, dues paid and the next year’s procedure carefully planned. All members are individually responsible for their costumes. They may make them — most of them do — or have them made to order.

The regalia consists of a large and resplendent crown of feathers, a wig, an apron, a jacket, a shirt, tights, trousers and moccasins. They vie with each other and with other tribes as to richness and elaborateness. Materials used include satins, velvet, silver and gold lame and various furs. The trimmings are sequins, crystal; colored and pearl beads, sparkling imitation jewels, rhinestones, spangles and gold clips put to extravagant use. Color is used without restraint. (Flame, scarlet and orange are possibly the preferred shades.)

Amazingly intricate designs are often worked out in beads and brilliants against the rich materials. A huge serpent of pearls may writhe on a gold lame breast, an immense spider of silver beads appears to be crawling on a back of flame satin. Sometimes a chief will choose to appear in pure white. A regal crown of snowy feathers, rising from a base of crystal beads, will adorn his head, and all other parts of his costume will be of white velvet heavily encrusted with rhinestones and crystals. All costumes are worn with the arrogance expressed in such songs as

Tu-way-pa-ka-way,

Bravest Indians in the land.

Tu-way-pa-ka-way.

They are on the march today.

Tu-way-pa-ka-way.

If you should get in their way,

Tu-way-pa-ka-way,

Be prepared to die.

Tu-way-pa-ka-way.

Oowa-a-a!

Oowa-a-a!

Ten years ago the various tribes actually fought when they met. Sometimes combatants were seriously injured. When two tribes sighted each other, they would immediately go into battle formation, headed by the first, second and third spy boys of each side. Then the two head chiefs would cast their spears — iron rods — into the ground, the first to do so crying, ‘Umba?’, which was an inquiry if the other were willing to surrender. The second chief replied, ‘Me no umba!’ There was never a surrender, never a retreat. There would follow a series of dances by the two chiefs, each around his spear, with pauses now and then to fling back and forth the exclamations, ‘Umba?’ ‘Me no umba!’ While this continued, sometimes for four or five minutes, the tribes stood expectantly poised, waiting for the inevitable break that would be an invitation for a free-for-all mêlée. Once a police officer was badly injured by an Indian’s spear. After that occurrence a law was passed forbidding the tribes of maskers to carry weapons.

Today the tribes are all friendly. The following song is a warning against the tactics of other days.

Shootin’ don’t make it, no no no no.

Shootin’ don’t make it, no no no no.

If you see your man sittin’ in the bush,

Knock him in the head and give him a push,

’Cause shootin’ don’t make it, no no.

Shootin’ don’t make it, no no no no.

The Golden Blades marched all day through main thoroughfares and narrow side streets. At the train tracks and Broadway came the news the spy boys had sighted the Little Red, White and Blues.

The tribes met on either side of a vacant space of ground, and with a whoop and loud cries.

‘Me, Chief “Happy Peanut.” My tribe Golden Blades. The other replied: ‘Me, Chief Battle Brown. My tribe Little Red, White and Blues.’

Palms still extended, they spoke as one, ‘Peace.’ Then they met, put arms around each other’s necks. Together they proceeded toward the nearest saloon, the two tribes behind them mingling and talking, the medicine men chanting a weird duet:

Follow me, follow me, follow me.

Wha-wha-wha-follow me.

Wha-wha-wha-follow me.

Shh-bam-hang the ham.

Wha-wha-wha-follow me.

Wha-wha-wha-follow me….

At the bar, the chiefs gulped jiggers of whiskey, then small beers as chasers. Members of both tribes crowded about and imbibed freely.

When decision was made to depart, each tribe filed out a different door, tambourines beating.

In the street Chief ‘Happy Peanut’s’ wife revealed to her husband that she didn’t think Chief Battle Brown’s mate was anything to brag about. ‘Shux!’ she sneered disgustedly. ‘She didn’t look so hot to me. She don’t have no life in her. Man, she’s gotta

Tu-way-pa-ka-way.

Use it like I use it!

Tu-way-pa-ka-way.

Do it like I do it!

Tu-way-pa-ka-way.

Like a good queen should.

Ee-e-e-e!’

The Queen, finishing her song, went into her dance. With hands lifted above her head, her fingers snapping to keep time, with tongue darting in a serpentlike movement in and out of her mouth and hips and stomach undulating, Queen ‘Happy Peanut’ executed an extremely unorthodox Indian dance. There was to be no doubt left in the minds of onlookers that she was red hot and full of life.

Suddenly the medicine man began hopping around and moaning over a figure lying prostrate on the ground. Utter astonishment caused the Queen to interrupt her dance when the identity of the form was announced. It was her spy girl, who had wandered slightly ahead of the others.

‘What’s the matter, she can’t take it?’ taunted a bystander.

Upon him the medicine man turned the full venom of his wrath, ‘Umm-m-m-n! A-a-a-a-ah!’ He made a sign, as if casting a spell over the tormentor, to the amusement of the gathering crowd.

The Queen briefly glanced at the girl.

‘She didn’t eat no breakfast this morning,’ she explained. ‘She’ll be all right. We is gonna eat at the next stop.’

Upon reaching South Claiborne Avenue, the spy boy ran back to the flag boy, the flag boy whispered to the wild man, who sent a runner scampering back to the chief. The Creole Wild West Indians were coming!

The Creole Wild Wests were already in a place, eating and drinking, when the Golden Blades caught up with them. The two tribes greeted each other in high spirits, with much shouting and laughter, all but Chief Brother Tillman.

On Mardi Gras it is traditional for Negroes to dress as Indians; they have done so for nearly a century

He leaned against the bar, his eyes, from which the power of vision was fast fading, troubled and brooding, his mind sad with the realization that this was probably the last time he would be able to take part in this Mardi Gras tradition. As far back as any Indian can remember there has always been a Brother Tillman.

‘They didn’t want me to go out this year,’ he said. ‘They thought I couldn’t see well enough. Well, we’ll see who can see. This is my only pleasure. Oh, yes, I drink, but I don’t drink for fun. I drink to hide the truth. Can you understand that? How about a drink? And let’s have some music! Come on, Peanut. What’s this, anyway? A funeral?’

But as soon as the dancing started, he was talking again. ‘It’s just that I’ve seen so much of this. It’s been my life. And to think I might not see it again. My sight isn’t good now, you know, but I wouldn’t let them know it because I might make another year. But let’s cheer up! Have another drink?’

When the time came to leave, Brother Tillman rose and led his band of Wild Creoles from the saloon, walking with erect dignity, his chin high. Though his costume was simple for a chief — plain buckskin trimmed with a black fringe, a crown of jet feathers on his head — he bore himself with unaffected but proud nobility.

Onward traveled the Golden Blades, chanting their strange songs, pausing to dance wildly, their tambourines relentlessly throbbing the monotonous rhythm. Drinking, eating, righting, loving, forgetting yesterday and tomorrow.

Laughing and singing one moment, imbued with genuine savagery the next, the Indians are still feared by many Orleanians, who will go to great lengths to avoid a tribe coming in their direction. It is almost as if those dock laborers and office-building porters have reverted for a day to the jungles of their ancestors.

Here and there the Golden Blades met other tribes, the Golden Eagles, the Yellow Pocahontas, the Red Frontier Hunters. They forced their way into packed bars and out again, laughing, cursing.

There were few mishaps, but a member or two strayed and vanished for the day. One daring ‘brave’ leaped aboard a truck filled with white maskers, who threw confetti on his crown and taunted him by derisively singing the famous old Creole cry,

Mardi Gras,

Chou-a-la-paille,

Run away,

Taille la l’sil!

Mardi Gras,

Chew the straw,

Run away

And tell a lie!

The day’s marching ended just after nightfall outside of the Japanese Tea Garden on St. Philip and North Liberty Streets.

Tired but still happy maskers gathered here. This is the Mecca of all Negroes on Mardi Gras Night, for here the Zulu Ball, the grand climax of the day, takes place. The Indians’ eyes are weary now, and their feet tired, but they never allow themselves to relax. They keep imbibing all the liquor they can get their hands on, keep their songs and dances going. A Baby Doll or two straggles past, mingling with the crowd. A Baby Doll has to keep busy all the time. At last, from within the Tea Gardens, come the strains of the Grand March as the Zulu Ball begins.

Inside the ceiling is decorated with colored paper, bright new lanterns shed vari-colored lights, palm leaves and coconuts contribute a tropical atmosphere, fresh sawdust is sprinkled on the floor and the six-piece orchestra is feeling extra hot.

The King and Queen lead the Grand March, and the band swings out with a torrid selection. No staid monarch is King Zulu. He leaves that for the white balls, where the kings must remain on their thrones most of the evening. King Zulu is out there trucking on down and giving the women a break. He’s really head man, and before the night is over he’s likely to feel like a super-Casanova, so many are the invitations whispered into his ear. Sometimes he makes a premature exit, one particularly fascinating damsel having proved too much for his will power. Two years ago, when King Zulu departed, so did most of the champagne and cake. After two hours Johnny Metoyer, then ruling Zululand with an iron hand, phoned his house.

‘He ain’t here,’ his wife informed Johnny, with vengeance. ‘I’m looking for him, too.’

Then Johnny did some thinking and he did some swearing. He and Charlie Fisher telephoned every saloon in town and visited a lot of them. At last His Majesty was located. He was in a beer parlor with four high yellow women, nine quarts of champagne and having the time of his life. The King was having a ball all by himself.

‘Niggers like you,’ was Royalty’s retort to the bawling out administered by Metoyer and Fisher, ‘ain’t supposed to get nothing.’

The Queen does all right at the Zulu Ball, too. If a girl can’t establish herself solid after this day and night, there is something radically wrong. She can sort out her propositions and pick one or a dozen of the best.

This Zulu Ball is the end of it. But it has been swell, all the maskers tell each other. The best year yet, they always agree. Zulus, Indians and Baby Dolls creep home jn the small hours of the morning, fall into bed and sleep most of the next day. There are few New Orleans Negroes at work or on the streets the day after the Carnival.

But that night they begin to straggle into the various bars along Gravier and Poydras Streets. There is the usual blare of music boxes, hot dancing, arguments and ‘corner loving.’ Liquor again pours down parched throats. It isn’t quite as exciting as Mardi Gras, but it isn’t dull. There is never a dull night in the streets where the Zulus and the Indians and the Baby Dolls live and play, in the streets where every night is Saturday night.

Most of the discussion is of the day before, but the subject always shifts to the Saint Joseph’s Night to come, as everyone looks eagerly forward to the next time they can really cut loose.

March 19, always an important date in the New Orleans calendar, has been a second Mardi Gras to Negroes for the past two decades. It is tradition that Zulus, Indians and Baby Dolls don their costumes that night and revive the spirit of Fat Tuesday for a few hours.

There are no parades, of course, but they wander about on foot, visiting the bars, having dances and parties at various places, strutting their stuff.

On Saint Joseph’s Night, 1941, the music box roared as usual, and in the arms of criminals, hopheads and hoboes the Baby Dolls danced and carried on. A huge woman, dressed as a gypsy queen in garish colors and her black face reddened with rouge, did a solo number, popped her fingers and messed around. Harry, that genius with the tambourine, beat it vigorously, and executed his inimitable dance on the crowded floor.

The Indians were there too. So were the ‘Gold Diggers’ an organization that gave the Baby Dolls some competition. They wore similar costumes, and, as if to assist them along the way, were accompanied by a ‘policeman’ — a male friend dressed in a burlesque uniform and cap, and carrying a club. They boasted escorts, too, each Gold Digger having a boy friend, who wore a ‘dress suit’ of pale blue satin, a top hat, and flourished a cane. The Gold Diggers wore blue satin costumes trimmed with white fur, false curls, and also carried canes. The liveliest of the crowd was also the largest, a Gold Digger weighing well over two hundred pounds, who, nevertheless, strutted her stuff with the grace and vigor of a bawdy sprite.

But the Western Girls, so called because one year they all came as Annie Oakley (these are a group of Negro female impersonators headed by ‘Corinne the Queen’), are perhaps the gayest of all. In evening gowns and wigs they try to outdo the real girls. The ones who top their extremely dark faces with golden-blonde and flaming red wigs are the funniest. As for Corinne, she always maintains her regal bearing, explaining, ‘I’m a real queen, and don’t nobody never forget it!’ The other ‘girls’ aren’t the least bit jealous, either, but love Corinne dearly because ‘she’s such a gay cat.’ And Corinne has genuine claims to majesty. In 1931 ‘she’ was Queen of the Zulus! That year the King said he was disgusted with women, so he selected Corinne to reign as his mate over all of the Negro Mardi Gras!

Chapter 2

Street Criers

The mule-drawn wagon pulls up at a corner in one of the residential sections of New Orleans. The Negro vendor cups his hands before his mouth and bellows:

If you don’t believe me jest pull down your blind! I sell to the rich,

I sell to the po’;

I’m gonna sell the lady

Standin’ in that do’. Watermelon, Lady!

Come and git your nice red watermelon, Lady!

Red to the rind, Lady!

Come on, Lady, and get ’em!

Gotta make the picnic fo’ two o’clock,

No flat tires today.

Come on, Lady!

Behind the hawker in the wagon is a tumbling pile of green serpent-striped melons; beside him on the seat is one halved to show that it is ‘red to the rind.’ Despite this, the melon you purchase will be ‘plugged’ as proof that yours is ripe. The peddler opens his mouth again to inform you that

If you don’t believe it jest pull down your blind.

You eat the watermelon and preee — serve the rind!

The vendor selling cantaloupe is an Italian. He sings out,

Fresh and fine,

Just offa de vine,

Only a dime!

The operator of a wagon selling a variety of vegetables offers this one:

Pretty little corn,

Butter beans, carrots,

Apples for the ladies!

Jui-ceee lemons!

Another, with curious humor, yells, ‘I got artichokes by the neck!’

The streets reverberate with their cries: ‘Come and gettum, Lady! I got green peppers, snapbeans, tur-nips! I got oranges! I got celery! I got fine ripe yellow banana! Tur-nips, Lady! Ba-na-na, Lady!’

These peddlers use every means imaginable to cart their wares — trucks, mules and wagons, pushcarts and baskets. A Negress will balance one basket on her head, carry two others, one in each hand, hawking any vegetables and fruit in season. Particularly discordant screams rend the mornings when it is blackberry season.

I got blackber — reeeees, Lady!

Fresh from th’ vine!

I got blackberries, Lady!

Three glass fo’ a dime.

I got blackberries!

I got blackberries!

BLACK — berrieeeeeeeees!

Negro youths often work in pairs, one on each side of a street, each carrying baskets and crying alternately or in unison: ‘I got mustard greens ’n Creole cabbage! Come on, Lady. Look what I got!’ Or, ‘Irish pota-tahs! Dime a bucket! Lady, you ought a see my nice Irish po-ta-tahs!’

Many housewives purchase their food supplies from these itinerant vendors, the prices often being a bit below those of the shops and markets. Many have regular peddlers or basket- ‘totin’’ Negresses who come daily to the kitchen door. They will often, even to this day, present favorite customers with a bit of parsley or a small bunch of shallots as lagniappe.

A truck at a curb in the business section of New Orleans is operated by an Italian who offers ‘Mandareeeens — nickel a dozen!’ A Negro in a spring wagon in the next block outdoes him with ‘Mandareens — twenty-five fo’ a dime!’

When strawberries appear, preceding the blackberry season, peddlers, both white and colored, both male and female, appear all over the city. Even Sunday mornings resound with cries of

Strawberries, Lady!

Fifteen cents a basket —

Two baskets for a quarter.

The housewives emerge, peer into the small boxes of berries, inspecting carefully, always raising the top layer of fruit to see the ones beneath. There is a little trade trick of putting the reddest and biggest berries on top, green, dry or small ones — the culls — underneath to which all Louisiana housekeepers are wise.

Between the strawberry and blackberry seasons cries of ‘Jewberry, Lady! Nice jewberries!’ may be heard. This is the dewberry season.

In Abbeville, an elderly French woman drives a mule before an ancient, creaky wagon, and peddles fruit and vegetables each morning, calling her wares in a weird mixture of French and Cajun English. Known as Madame Mais-La, she pulls up before a house and announces: ‘Hello, dere! Voulez-vous légumes au-jourd’hui? Des bonnes carrots. Des bonnes papates douces. Des pommes de terre. Des choux-fleurs. Non? Pas ça aujourd’hui. Bien. Geedy up, dere!’

The vending of food in New Orleans streets is a custom as old as the city itself. In earlier days the peddlers were even more numerous. Buying from these wandering marchandes was extremely convenient. Prices were low, the produce of good quality; often it was possible, after a bit of wrangling, to strike off a bargain.

Earlier counterparts of present-day hawkers were the Green Sass Men, no longer in existence. The Daily Picayune of July 24, 1846, describes them thus:

Most of the French and American slave-owners of long ago were a thrifty lot, and those slaves too old to be of other use were often put out into the city streets to peddle the surplus products of the plantations. Throughout the year, day in, day out, their cries resounded through the streets of New Orleans. All masters were required to purchase licenses for their slaves, but often added thousands of dollars per year to their incomes by so doing. De Boré, of sugar fame, who owned a huge plantation in New Orleans where Audubon Park now spreads, ‘produced at least six thousand dollars per annum’ in this fashion, according to one authority. Newspapers of the period criticized slave street-vending as a ‘very picayunish business,’ but it lifted many of the Negroes’ owners into affluence.

Each season had its special commodities. Early spring saw the arrival of strawberries, of Japanese plums. Later, watermelons, dewberries, blackberries and figs appeared. Wild ducks, rice birds and other game were sold on the streets during winter. At the French Market Choctaw Indian squaws sat stoically at the curbs, offering gumbo filé — powdered sassafras, frequently used instead of okra to thicken gumbo — other herbs and roots, baskets and pottery. Fat Negresses in starched white aprons and garish tignons sold cakes, molasses and coffee dripped while you waited. Other peddlers offered everything from cheap jewelry to live canaries in cages. Chickens, alive but limply resigned to fate, trussed up in bunches like carrots, were carried up and down the city streets by men who poked their heads into the windows of homes and yelled, ‘Cheeec-ken, Madame? Nice fat spring cheee-ken?’

The peddlers of fish probably were the most insistent. The Daily Picayune of April 4, 1889, reports:

A salesman of oysters, carrying his merchandise in tin pails, was also common at one time, crying,

Or sometimes,

Get your fresh oysters from the Oyster Man!

Bring out your pitcher, bring out your can,

Get your nice fresh oysters from the Oyster Man!

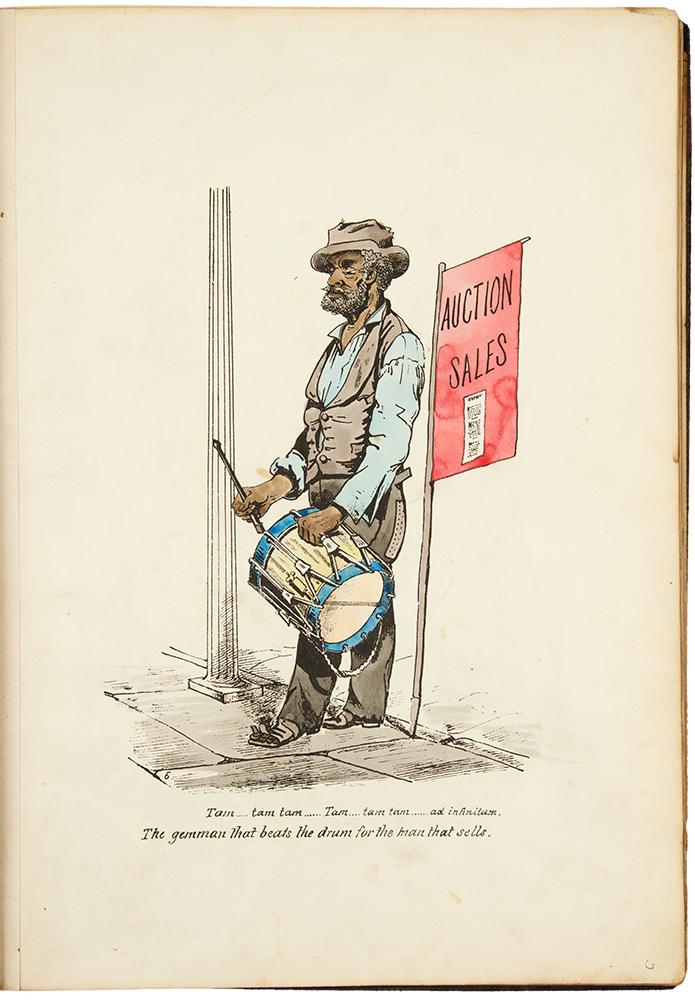

There was the Icecream Man, humorously depicted by Léon Fremeaux, in a volume of sketches titled New Orleans Characters, as a barefooted Negro wearing patched trousers, holding in one hand a white cloth, carrying in his other a basket, and on his head, at a perilous balance, an icecream freezer! His cry was

Crême à la vanille!

Or, facetiously,

Brown sugar and rotten aig!

Fresh milk and buttermilk were sold on the streets, the fresh milk from horse-drawn wagons described by the Daily Picayune as ‘… a tall green box, set between high wheels and almost always driven by Gascons. The two large bright brassbound cans that ornamented the front of the wagon, compelled the driver to stand up much of the time in order to see clearly before him.’ The Buttermilk Man carried his large can of buttermilk through the streets several times a week, crying, ‘Butter-milk! Butter-milk, Lady?’

Very early in the life of the Creole city, even water was sold in this fashion, being dispensed from carts loaded with huge hogsheads. Wine, too, was often vended.

THE BREAD AND CAKE VENDORS

The most famous of these were the cala vendors. A cala is a pastry which originated among Creole Negroes — a thin fritter made with rice and yeast sponge. Creoles did not have the prepared yeast cakes sold today, so yeast was concocted the night before, of boiled potatoes, corn meal, flour and cooking soda, left in the night air to ferment, then mixed with the boiled rice and made into a sponge. The next morning flour, eggs, butter and milk were added, a stiff batter mixed, and the calas formed by dropping spoonfuls into a skillet.

‘Belles calas, Madam! Tout chauds, Madame, Two cents!’ thus called the cala vendors for years. A long cry was,

Belles calas,

Madame, mo gaignin calas,

Madame, mo gaignin calas,

Madame, mo gaignin calas;

Mo guaranti vous ye bons

Beeelles calas … Beeelles calas.

Madame, mo gaignin calas,

Madame, mo gaignin calas,

Si vous pas gaignin 1’argent,

Goutez c’est la mem’ chose,

Madame, mo gaignin calas tou, tou cho

Beeles calas . .. Beeelles calas,

Tou cho, tou cho, tou cho.

Madame, mo gaignin calas,

Madame, mo gaignin calas,

Tou cho, tou cho, tou cho.

Beautiful rice fritters,

Madame, I have rice fritters,

Madame, I have rice fritters,

Madame, I have rice fritters,

I guarantee you they are good

Fine rice fritters … Fine rice fritters.

Madame, I have rice fritters,

Madame, I have rice fritters,

If you have no money,

Taste, it’s all the same,

Madame, I have rice fritters, quite, quite hot.

Fiiiine rice fritters … Fiiiine rice fritters,

All hot, all hot, quite hot.

Madame, I have rice fritters,

Madame, I have rice fritters,

Quite hot, quite hot, quite hot.

Clementine, a Negress, well-dressed in a bright tignon, fichu of white lawn, tied with a large breast pin, a starched blue gingham skirt and stiff snowy apron, would sing,

Madame, mo gaignin calas,

Madame, mo gaignin calas,

Tou cho, tou cho, tou cho.

Beeeeeelles calas — Belles calas

A madame mo gaignin calas,

Mo guaranti vous ye bons!

Another Negress sold her calas in front of the old Saint Louis Cathedral, cooking them in a pan over a small furnace, while the customer waited. Without raising her voice she would mutter hoarsely and incessantly, ‘Mo gaignin calas … Madame, mo gaignin calas … Calas, calas, calas, calas, tou cho, calas, calas, calas; Mo gaignin calas, Madame … calas, calas, calas, calas.…’

Some vendors sold not only calas of rice, but also calas of cow-peas, crying,

Calas au riz calas aux feves!

Another cry was

Tout chauds — all hot!

Calas — calas — tout chauds,

Belles — calas — tout chauds,

Madame, mo gaignin calas,

Madame, mo gaignin calas, tou

Chauds tou chauds!

One of the last professional cala vendors on New Orleans streets was Richard Gabriel, a colored descendant of these Creole Negroes. He improved the system somewhat, pushing a cart similar to the sort used by the peanut vendors, and chanting in more modern fashion,

We give it to the sweet brownskin, peepin’ out the door.

Tout chaud, Madame, tout chaud!

Git ’em while they’re hot! Hot calas!

Make you smile the livelong day.

Calas, tout chauds, Madame, Tout chauds!

Git ’em while they’re hot! Hot calas!

Other songs are

More you eatta, more you wanta eatta.

Get ’em while they’re hotta. Hot calas!

Tout chauds, Madame, tout chauds.

And

Put on that Sunday morning smile, to last the whole day ’round.

Tout chauds, Madame, tout chauds!

That’s how two cups of café, fifteen cents calas can make

You smile the livelong day.

Tout chauds, Madame, tout chauds!

Get ’em while they’re hot! Hot calas!

There used to be two cala women who would sing alternately:

Calas, Calas, — all nice and hot

All nice ’n hot — all nice ’n hot — all nice ’n hot.…

Well known was the Cymbal Man, who, according to the Daily Picayune of July 24, 1846, confined his rambles to the French section of New Orleans, offering also ‘doughnuts and crullers,’ which were favorites with the Creoles. His musical ‘toooo-shoooo-oooo’ never failed to bring most of them out.

The Corn Meal Man, noted for his wit and humor, would prowl the streets, blowing on a small brass trumpet worn on a cord about his neck. His greeting was usually, ‘Bon jour, Madame, Mam - zelle! Fresh corn meal, right from the mill. Oui, Mam - zelle!’ accompanied by a hearty laugh. The Daily Delta of June 3, 1850, reports him doing business on horseback, saying, ‘… his fat, glossy horse looks as if he partook of no scant portion of the corn meal!’ A very early corn meal peddler was known as Signor Cornmeali.

Among the most famous of the cake vendors were the Gaufre Men or Shaving Cake Men, who sold not shaving soap, but pastries that had the appearance of timber shavings. These were kept in a tin box strapped to the back, while the Gaufre Man announced his approach by beating on a metal triangle as he strode the city streets. The last Gaufre Man, bewhiskered but always clean and neatly attired, never revealed the secret of his thin, crisp, cone-shaped pastries. When he died, the recipe died with him, and gaufres are now unknown in New Orleans.

Hot potato cakes, made usually of sweet potatoes, were sold by Negro women. These vendors, Emmet Kennedy says, were heard mostly in the French Quarter around nightfall. In his Mellows he describes their cry as follows:

Bal pam pa-tat, Madame,

Ou-lay-ou Le Bel Pam Patat,

Pam patat!

Everything the old Creole Negresses sold was either ‘bel’ — beautiful — or ‘bon’ — good.

A bread made of Irish potatoes was also sold, to the following song:

Pain patatte,

Pain patatte., Madame,

Achetez pain patatte,

Madame, mo gaignin pain patatte.

Potato bread,

Potato bread, Madam,

Buy potato bread,

Madam, I have potato bread.

Hot pies were another favorite commodity, the vendor carrying his wares in a cloth-covered basket, crying, ‘Ho’ pies — chauds! Ho’ pies — chauds!’

There are modern versions of these last. Each day pie peddlers appear on the docks of New Orleans, moving among the longshoremen, carrying their pies — and often sandwiches and candy — in a basket. Occasionally a pie man will appear in one of the residential sections, with a monotonous cry of ‘Hot pies — hot pies — hot pies — hot pies!’ A Negro woman, always dressed in snowy white, hawks pies and sandwiches through the business district of the city, rolling her merchandise along in a baby carriage.

At least one man still sells bread on the streets. Pushing a cart he calls out, ‘Bread Man! Bread Man! I got French bread, Lady. I got sliced bread. I got raisin bread. Lady! I got rolls, Lady! Bread Man, Lady!’

He washes his face in a frying-pan,

He makes his waffles with his hand,

Everybody loves the Waffle Man.

For years those who believed this little ditty ran out at the shrill blast of the Waffle Man’s bugle. Children eagerly thrust their nickels forward to purchase one of his delicious hot waffles sprinkled liberally with powdered sugar. His wagon, horse-drawn, was usually white and yellow and set on high wheels. One Waffle Man still appears daily in New Orleans, vending waffles from a brilliant red-and-yellow wagon. But now he caters mostly to fully grown males of the stock-exchange neighborhood.

THE CANDY AND FLOWER VENDORS

The Candy Man, according to the Daily Picayune of July 15, 1846, ‘carried his caraway comfits and other sweets in a large green tin chest upon which was emblazoned, in the brightest yellow, two razors affectionately crossed over each other.’ Unlike the other vendors, this Candy Man had no cry, but attracted attention by beating on a metal triangle. Until a few years ago, later Candy Men, driving squarish, high wagons, paused at corners, blew piercing blasts on trumpets and sold taffy in long, wax-paper-wrapped sticks.

Pralines have been sold on New Orleans streets through all the city’s history, and always the delicious Creole confections of brown sugar and pecans have been vended by Negresses of the ‘Mammy’ type. Today they appear, garbed in gingham and starched white aprons and tignons, usually in the Vieux Carré, though now they represent modern candy shops. ‘Belles pralines!’ they cry. ‘Belles pralines’ Day by day they sit in the shadows of the ancient buildings, fat black faces smiling at the passers-by, fanning their candies with palmetto fans or strips of brown wrapping paper. Usually, besides the pralines, Mammy dolls and other souvenirs are sold.

Flowers are not sold on the streets as frequently as they are in some other cities, but in the Vieux Carré elderly flower women and young girls and boys peddle corsages of rosebuds and camellias in the small bars and cafés, chanting at your table, ‘Flowers? Pretty flowers for the lady?’

THE CHARCOAL MAN

Until recently practically everyone employed Negro washwomen, who boiled clothes and other washing over small furnaces in the backyards, and charcoal was always in demand. Almost every day this familiar cry rang through the streets. Lafcadio Hearn described one cry of the Charcoal Man’s as

Coaly — coaly; coaly — coaly — coal — coal — coal.

Coaly — coaly!