Anthology

of Louisiana Literature

Madison Tensas.

Odd Leaves from the Life of a Louisiana “Swamp Doctor.”

CONTENTS.

- THE CITY PHYSICIAN versus THE SWAMP DOCTOR

- MY EARLY LIFE

- GETTING ACQUAINTED WITH THE MEDICINES

- A TIGHT RACE CONSIDERIN’

- TAKING GOOD ADVICE

- THE DAY OF JUDGMENT

- A RATTLESNAKE ON A STEAMBOAT

- FRANK AND THE PROFESSOR

- THE CURIOUS WIDOW

- THE MISSISSIPPI PATENT PLAN FOR PULLING TEETH

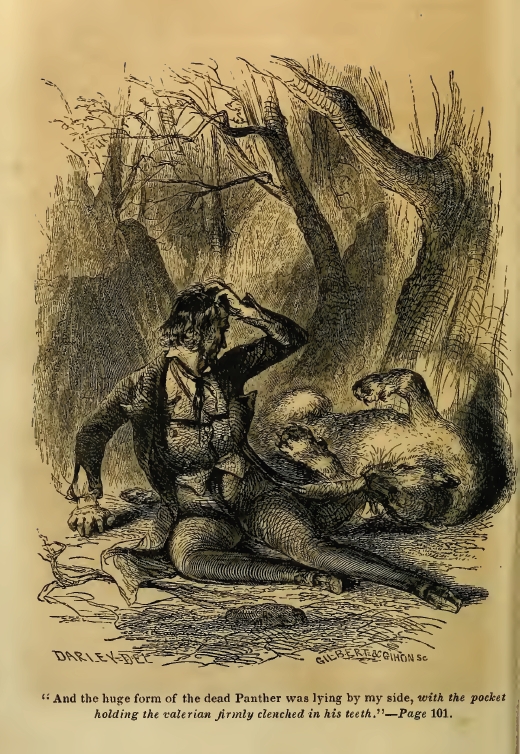

- VALERIAN AND THE PANTHER

- SEEKING A LOCATION

- CUPPING AN IRISHMAN

- BEING EXAMINED FOR MY DEGREE

- STEALING A BABY

- THE “SWAMP DOCTOR” TO ESCULAPIUS

- MY FIRST CALL IN THE SWAMP

- THE MAN OF ARISTOCRATIC DISEASES

- THE INDEFATIGABLE BEAR-HUNTER

- LOVE IN A GARDEN

- HOW TO CURE FITS

- A STRUGGLE FOR LIFE

LIST OF ENGRAVINGS.

- A TIGHT RACE CONSIDERIN’

“She tuk off her shoe, and the way a No.

10 go-to-meetin’ brogan commenced

givin’ a hoss particular Moses, were a caution

to hoss-flesh.”

- A RATTLE-SNAKE ON A STEAMBOAT

“But hardly had he reached the deck, when

he discovered the monster — his

head drawn back ready for striking.”

- VALERIAN AND THE PANTHER

“And the huge form of the dead panther

was lying by my side, with the

pocket holding the valerian firmly clenched

in his teeth.”

- STEALING A NIGGER BABY

“My cloak flew open as I fell, and the force of the

fall bursting its envelope,

out, in all its hideous realities, rolled the infernal

imp of darkness.”

- THE INDEFATIGABLE BEAR-HUNTER

“The way that bar’s flesh giv’ in to

the soft impresshuns of that leg, war an

honor to the mederkal perfeshun for having

invented sich a weepun.”

- A STRUGGLE FOR LIFE

“Closer and firmer his gripe

closed upon my throat, barring out the sweet

life’s breath.”

THE CITY PHYSICIAN

versus

THE SWAMP DOCTOR.

THE city

physician, or the country doctor of an old-settled

locality, with all the appliances of cultivated and

refined life around them; possessing all the numberless

conveniences and luxuries of the sick-room; capable of

controlling the many adverse circumstances that exert such a

pernicious influence upon successful practice; having at command

the assistance, in critical and anomalous cases, of scientific

and experienced coadjutors; the facilities of good roads; the

advantages of comfortable

dwellings, easy

carriages, and the pleasures of commingling with a

cultivated, mild,

refined society, cannot fully realize and appreciate the

condition of their less favoured, humble brethren, who, impelled

by youthfulness,

poverty, defective education, or the reckless spirit of

adventure, have taken up their lot with society nearly in

its primitive condition, and dispense the blessings of

their profession to the inhabitants of a country, where the

obscure bridle-path, the unbridged water-courses, the deadened

forest trees, the ringing of the

woodman’s axe, the humble log cabin, the homespun dress, and all

the many sober, hard realities of pioneer life, attest the

youthfulness of the settlement.

The city

physician may be of timorous nature and weak

and effeminate constitution: the “swamp doctor,” whose

midnight ride is often saluted by the scream of the panther,

must be of courageous nature, and in physical endurance

as hardy as one of his own grand alluvial oaks, whose

canopy of leaves is many a night his only shelter.

The city

physician may be of fastidious taste, and

exquisiteness of feeling; the swamp doctor must have the

unconcernedness of the dissecting-room, and be prepared

to swallow his peck of dirt all at once.

The city

physician must be of polished manners and

courtly language: the swamp doctor finds the only use he

has for bows, is to escape some impending one that

threatens him with

Absalomic fate

the only necessity for

courtly expression, to induce some bellicose “squatter” to

pay his bill in something besides hot curses and cold lead.

The city

physician, fast anchored in the sublimity of

scientific expression, requires a patient to “inflate his lungs

to their utmost capacity;” the swamp doctor tells his to

“draw a long breath, or swell your d——dest:” one calls an

individual’s physical peculiarities, “idiosyncrasy;” the

other terms it “a fellow’s nater.”

The city

physician sends his prescriptions to the drug

store, and gives himself no regard as to the purity of the

medicine; each swamp doctor is his own

pharmacien,

and

carries his drug store at the saddle.

The city

physician rides in an easy carriage over well

paved streets, and pays toll at the bridge; we mount a

canoe, a pair of mud boots, sometimes a horse, and

traverse, unmindful of exposure or danger, the sullen

slough or angry river.

The city

physician wears broadcloth, and looking in his

hat reads, “Paris;” we adorn the outer man with homespun,

and gazing at our graceful castors remember

the identical hollow tree in which we caught the coon that

forms its fair outline and symmetrical proportions.

The city

physician goes to the opera or theatre, to relax,

and while away a leisure evening. The swamp doctor

resorts for the same purpose to a deer or bear hunt, a

barbacue or

bran dance

and

generally ends by becoming

perfectly hilarious, and evincing a determination to sit up

in order that he can escort the young ladies home before

breakfast.

The city

physician, compelled to keep up appearances,

deems a library of a hundred authors a moderate collection;

the swamp doctor glories in the possession of

“Gunn’s Domestic Medicine,”

and the “Mother’s Guide.”

The city

physician has a costly Parisian instrument for

performing operations, and scorns to extract a tooth; the

swamp doctor can rarely boast of a case of amputating

instruments, and practices dentistry with a gum lancet and

a pair of pullikens.

The city

physician, with intellect refined, but feelings

vitiated by the corruptings and heart-hardenings of modern

polished society, views with utter indifference or affected

sympathy the dissolution of body and soul in his patients:

but think you, we can see

depart unmoved those with

whom we have endured privations, have been knit like

brothers together by our mutual dangers; with whom we

have hunted, fished, and shared the crust and lowly couch;

with whom we have rejoiced and sorrowed; think you

we

can see them go down to the grave with tearless eyes, with

unmoved soul? If we can, then blot out that expression so

accordant with common sentiment, “God made the

country, and man the town.”

The city

physician sends the poor to the hospital, and

eventually to the dissecting-room; we tend and furnish

them gratuitously, and a proposal to dispose of them

anatomically would, in all probability, put a knife into us.

One, with a

sickly frame, anticipates old age; the other,

with a vigorous constitution, knows that exposure and

privation will cut him off ere his meridian be reached.

The city

physician has soft hands, soft skin, and soft

clothes: we have soft hearts but hard hands; we are rough

in our phrases, but true in our natures; our words do not

speak one language and our actions another; what we

mean we say, what we say we mean; our characters, when

not original, are impressed upon us by the people we

practice among and associate with, for such is the character

of the pioneers and pre-emptionists of the swamp.

To sum up the

whole, the city physician lives at the top

of the pot, the swamp doctor scarcely at the rim of the

skillet: one is a delicate carpet, which none but the nicest

kid can press; the other is a cypress floor, in which the

hobnails of every clown can stamp their shape: one is the

breast of a chicken, the other is a muscle-shell full of

cat-fish: one is quinine, the other Peruvian bark: and so on in

the scale of proportions.

I have

contrasted the two through the busy, moving

scenes of life; let me keep the curtain from descending

awhile, till I draw the last and awful contrast.

Stand by the

death-bed of the two, in that last and

solemn hour, when disease has prescribed for the patient,

and death, acting the

pharmacien,

is

filling the ℞.

In a

close, suffocating room, horizontalized on a feather bed; if a

bachelor, attended by a mercenary nurse; his departure

eagerly desired by a host of expectant, envious

competitors; with the noise of drays, the shouts of the

busy multitude, and the many discordant cries of the city

ringing through his frame, the soul of the city physician

leaves its mortal tenement and wings its way to heaven

through several floors and thicknesses of mortar and brick,

whilst the sobs of his few true friends float on the air

strangely mingled with “Pies all hot!” “The last

’erald!”

and “Five dollars reward, five dollars reward, for the lost

child of a disconsolate family!”

The swamp

doctor is gathered unto his fathers ’neath the

greenwood tree, couched on the yielding grass, with the

soft melody of birds, the melancholy cadence of the summer

wind, the rippling of the stream, the sweet smell of flowers,

and the blue sky above bending down as if to embrace him,

to soothe his spirit, and give his parting soul a glance of

that heaven which surely awaits him as a recompense for all

the privations he has endured on earth; whilst the pressure

on his palm of hard and manly hands, the tears of women

attached to him like a brother by the past kind ministerings

of his Godlike calling, the sobs of children, and the

boisterous grief of the poor negroes, attest that not

unregarded or unloved he hath dwelt on earth: a sunbeam

steals through the leafy canopy and clothes his brow with a

living halo, a sweet smile pervades his countenance, and

amidst all that is beauteous in nature or commendable in

man, the swamp doctor sinks in the blissful luxuries of

death; no more to undergo privation and danger, disease or

suffering. He hath given his last pill, had his last draught

protested against; true

to the instincts of his profession, he, no doubt, in the

battling troop of the angels above, if feasible, will still

continue to charge.

MY EARLY LIFE.

UPON what

slender hinges the gate of a man’s life turns, and

what trifling things change the tenor of his being, and

determine in a moment the direction of a lifetime! Who

inhales his modicum of

azote

and oxygen, that cannot verify

in his own person that we are the creatures of

circumstances, and that there is a hidden divinity that

shapes our ends, despite the endeavours of the pedagogue,

man, to paddle them out of shape?

Some writer of

celebrity has averred, and satisfactorily

proven to all of his way of thinking, by a chain of logical

deductions, that the war of 1812, the victory of New

Orleans, the elevation of Jackson to the presidency, the

annexation of Texas,

General Taylor’s

not possessing the

proportions of Hercules, and a sad accident that occurred

to one of the best of families very recently, all was the

inevitable effect of a quiet unobtrusive citizen in Maryland

being charged some many years ago with hog stealing.

Were I writing

a library instead of a volume, I would take

up, for the satisfaction of my readers, link by link, the chain

of consequences, from the mighty to the insignificant;

also, if time and eternity permitted, trace the genealogy of

the memorable porker (upon whose forcible seizure all

these events depended), back to the time when Adam was

not required to show a tailor’s bill unpaid, as a portent of

gentility, or Eve thought it a wife’s duty to henpeck her

husband.

As I cannot do

this, I will, by an analogous example,

show that equally — to me at least — important

consequences have been deduced from as unimportant

and remote causes; and that the writing of this volume, my

being a swamp doctor in 1848, and having been steamboat

cook, cabin-boy, gentleman of leisure, plough-boy,

cotton-picker,

and almost a printer, depended when I was ten

years old on a young lady wearing “No. 2” shoes, when

common sense and the size of her foot whispered “fives.”

And now to show the connexion between these remote facts.

The death of my

mother when I was very young breaking

up our family circle, I became an inmate of the family of a

married brother, whose wife, to an imperious temper, had,

sadly for me, united the companionship of several younger

brothers, whose associates I became when I entered her

husband’s door.

Living in a free state, and his straitened

circumstances permitting him but one hired servant, much

of the family drudgery fell upon his wife, who up to my

going there devolved a portion upon her brothers, but

which all fell to my share as soon as I became domiciliated. I

complained to my brother; but it was a younger brother

arraigning a loved wife, and we all know how such a suit

would be decided. Those only who have lived in similar

circumstances can appreciate my situation; censured for

errors and never praised for my industry, the scapegoat of

the family and general errand-boy of the concern, waiting

upon her brothers when I would fain have been at study or

play, mine was anything but an enviable life. This condition

of things continued until I had passed my tenth year, when,

grown old by drudgery and wounded feelings, I determined

to put into effect a long-cherished plan, to run away and

seek my fortune wheresoever chance might lead or destiny

determine.

By day and by

night for several years this thought had

been upon me; it had grown with my growth, and acquired strength

from each day’s developement of fresh

indignities, filling

me with so much resolution, that the boy of ten had the

mental strength of twenty to effect such a purpose. I

occupied my few leisure hours in building airy castles of

future fortune and distinction, and in marking out the

preparatory road to make Providence my guide, and have

the world before me, where to choose.

One evening,

just at sunset, I was seated on the lintel of

the street-door, nursing one of my nephews, and affecting

to still his cries, the consequence of a spiteful pinch I had

given him, to repay some indignity offered me by his

mother, when my attention was attracted to a young lady,

who, apparently in much suffering, was tottering along,

endeavouring to support herself by her parasol, which she

used as a cane. To look at me now with my single bed,

buttonless shirts, premature wigdom, and haggard old-bachelor

looks, you would scarcely think I am or was ever

an admirer of the sex. But against appearances I have

always been one; and boy as I was then, the sight of that

young woman tottering painfully along, awoke all my

sensibilities, and made the fountain of sympathy gush out

as freely as a child swallowing lozenges. Overcoming my

boyish diffidence, as she got opposite the door, I

addressed her, “Miss, will you not stop and rest? I will get

you a chair, and you can stay in the porch, if you will not

come in the house.” “Thank you, my little man,” she

gasped out, and attempted to seat herself in the chair I had

brought, but striking her foot against the step the pain was

so great, that she shrieked out, and fell dead, as I thought,

on the floor.

Frightened

terribly to think I had brought dead folks

home, I joined my yell to her scream, as a prolongation,

which outcry brought my sister-in-law to the scene. The

woman prevailing, she carried her in the house, and

shutting the door to keep out curious eyes, which began

to gather round, she set to restoring her uninvited guest,

which she soon accomplished. As soon as she could

speak, she gasped out, “Take them off, they are killing

me!” — pointing to her feet. This, with difficulty, was

effected, and their blood-stained condition showed how

great must have been her torment. She announced herself

as the daughter of a well-known merchant of the city, and

begged permission to send me to her father’s store, to

request him to send a carriage for her. Assent being given,

she gave me the necessary directions to find it, and off I

started. It was near the river.

On my way to

the place, as I reached the river, I

overtook a gentleman apparently laden down with

baggage. On seeing me he said, “My lad, I will give you a

quarter if you will carry one of these bundles down to that

steamboat,” pointing to one that was ringing her last bell

previous to starting to New Orleans. This was a world of

money to me then, and I readily agreed. Increasing our

pace, we reached just in time the steamer, between which

and the place he had accosted me, I had determined, as the

present opportunity was a good one, to put in execution

my long-cherished plan, and run away from my home then.

Its accomplishment was easy. Following my employer on

board, I received my quarter; but instead of going on

shore, I secreted myself on board, until the continued puff

of the steamer and the merry chant of the firemen assured

me we were fairly under way, that I was fast leaving my

late home and becoming a fugitive upon the face of the

waters, dependent upon my childish exertions for my daily

bread, without money, save the solitary quarter, without a

change of clothes; no friend

to counsel me save the monitor within, a heart made aged

and iron by contumely and youthful suffering.

Emerging from

my concealment, I timidly sought the

lower deck and sat me down upon the edge of the boat,

and singling out some spark as it rose from the chimney,

strove childishly to draw some augury of my future fate

from its long continuance or speedy extinction.

The city was

fast fading in the distance. I watched its

receding houses, for, while they lasted, I felt as if I was not

altogether without a home. A turn of the river hid it from

sight, and my tears fell fast, for I was also leaving the

churchyard which held my mother, and I then had not

grown old enough to read life’s bitterest page, to separate

dream from reality, and know we could meet no more

on earth; for oftentimes in the quiet calm of sleep, in the

lonely hours of night, I had seen her bending over my tear-wet

pillow, and praying for me the same sweet prayer that

she prayed for me when I was her sinless youngest born,

and I thought in leaving her grave I should never see her

more, for how, when she should rise again at night, would

she be able to find me, rambler as I was?

With this huge

sorrow to dampen my joy at acquiring my

liberty, chilled with the night air I was sinking into sleep in

my dangerous seat, when the cook of the boat discovered

me, and shaking me by the arm until I awoke, took me into

the

caboose, and giving me my supper, asked me, “What I

was doing there, where I would be certain to fall overboard

if I went to sleep?” I made up a fictitious tale, and finishing

my story, asked him if he could assist me in getting some

work on the boat to pay my passage, hinting I was not

without experience in his department, in washing dishes,

cleaning knives, &c. This was just to his hand; promising

me employment and

protection, he gave me a place to sleep in, which, fatigued

as I was, I did not suffer long to remain unoccupied.

The morrow

beheld me regularly installed as third cook

or scullion, at eight dollars a month. This, to be sure, was

climbing the world’s ladder to fame and fortune at a snail’s

pace; but I was not proud, and willing to bide my time in

hope of the better day a-coming. My leisure hours, which

were not few, were employed in studying my books, of

which I had a good supply, bought with money loaned me

by my kind friend the cook.

I improved

rapidly in my profession, till one day my

ambition was gratified by being allowed to make the bread

for the first cabin table. This I executed in capital style,

with

the exception of forgetting in my elation to sift the meal,

thereby kicking up considerable of a stir when it came to be

eaten, and causing my receiving a hearty curse for my

carelessness, and a threat of a rope’s end, the exercise of

which I crushed by seizing a butcher knife in very

determined style, and the affair passed over.

I remained on

board until I had ascended as high as

second cook, when I got disgusted with the kitchen and

aspired to the cabin. I had heard of many cabin-boys

becoming captain of their own vessels, but never of one

cook, — except

Captain Cook,” and he became one from

name, not by nature or profession. There being no vacancy

on board, I received my wages and

hired at V—— as cabin boy

on a small steamboat running as packet to a small town,

situated on one of the tributaries of the Mississippi.

On my first

trip up I recollected that I had a

brother

living in the identical town to which the steamer was

destined, who had been in the south for several years,

and, when I last heard from him, was doing well in the

world’s ways.

I thought that

as I would be landing every few days at

his town, it would be only right that I should call and see him.

He was

merchandising on a large scale, I was informed

by a gentleman on board, a planter in one of the middle

counties of Mississippi, who, seeing me reading in the

cabin after I had finished my labour of the day, opened a

conversation with me, and, extracting my history by his

mild persuasiveness, offered to take me home with him

and send me to school until my education for a profession

was completed. But my independence spurned the idea of

being indebted to such an extent to a stranger; perhaps I

was too enamoured of my wild roving life. I refused his

offer, thanking him gratefully for the kind interest he

seemed to take in me. He made me promise, that if I

changed my mind soon, I would write to him, and gave me

his direction, which I soon lost, and his name has passed

from my recollection.

On reaching M——, I strolled up in town and inquired the

way of a negro to Mr. Tensas’ store. He pointed it out to

me, and I entered. On inquiry for him, I found he was over

at his dwelling-house, which I sought. It was a very pretty

residence, I thought, for a bachelor; the walks were nicely

gravelled, and shrubbery appropriately decorated the

grounds.

I knocked at

the door boldly; after a short delay it was

opened by quite a handsome young finely dressed lady.

Thinking I was mistaken in the house, I inquired if my

brother resided there? She replied, “that he did;” and

invited me to wait, as he would soon be home. Walking in,

after a short interval my brother came. Not remarking me at

first, he gave the young lady a hearty

kiss, which she returned with interest. I concluded she

must be his housekeeper. Perceiving me, he recognised me

in a moment, and gave me an affectionate welcome,

bidding me go and kiss my sister-in-law, which, not

waiting for me to do, she performed herself.

My brother was

very much shocked when he heard of

my menial occupation, and used such arguments and

persuasives to induce me to forsake my boat-cabin for his

house, that I at length yielded.

He intended

sending me the next year to college, when

the

monetary crash came over the South, and the

millionaire of to-day awoke the penniless bankrupt of the

morrow. My brother strove manfully to resist the

impending ruin, but fell like the rest, and I saw all my

dreams of a collegiate education vanishing into thin smoke.

Why recount the

scenes of the next five years? it is but

the thrice-told tale, of a younger brother dependent upon

an elder, himself dependent upon others for employment

and a subsistence for his family; his circumstances would

improve — I would be sent to school — fortune would

again lower, and I, together with my sister-in-law, would

perform the menial offices of the family.

My sixteenth

birthday was passed in the cotton-field, at

the tail of a plough, in the midst of my fellow-labourers,

between whom and myself but slight difference existed. I

was discontented and unhappy. Something within kept

asking me, as it had for years, if it was to become a toiler

in the cotton-fields of the South, the companion of

negroes, that I had stolen from my boyhood’s home? was

this the consummation of all my golden dreams?

My prospects

were gloomy enough to daunt a much

older heart. Poverty shut out all hopes of a collegiate

education and a profession. Reflection had disgusted me

with a steamboat. I determined to learn a trade. My

taste for reading naturally inclined me to one in which I

could indulge it freely: it was a printer’s.

Satisfactory

arrangments were soon made with a

neighbouring printer and editor of a country newspaper.

The day was fixed when he would certainly expect me; if I

did not come by that time he was to conclude that I had

altered my determination, and he would be free to procure

another apprentice.

A wedding was

to come off in the family for which I

worked, in a short time, and they persuaded me to delay my

departure a week, and attend it. I remained, thinking my

brother would inform the printer of the cause of my

detention. The wedding passed off, and the next morning,

bright and early, I bid adieu, without a pang of regret, to my

late home, and started for my new master’s, but who was

destined never to become such; for on reaching the office I

learnt that my brother had failed to inform him why I

delayed, and he had procured another apprentice only the

day before. So that wedding gave one subject less to the

fraternity of typos, and made an indifferent swamp doctor

of matter for a good printer.

I returned home

on foot, wallet on my back, and

resumed my cotton-picking, feeling but little disappointed.

I had shaken hands too often with poverty’s gifts to let

this additional grip give me much uneasiness.

The season was

nearly over, and the negroes were

striving to get the cotton out by Christmas, when one

night at the supper table — the only meal I partook of with

the family — my brother inquired,

“How would you

like to become a doctor, Madison?”

I thought he

was jesting, and answered merely with a

laugh. Become a doctor, a professional man, when I was

too poor to go to a common school, was it not ludicrous?

“I am in

earnest. Suppose a chance offered for you to

become a student of medicine, would you accept it?” he

said.

It was not the

profession I would have selected had

wealth given me a choice, but still it was a means of

acquiring an education, a door through which I might

possibly emerge to distinction, and I answered, “Show me

the way, and I will accept without hesitation.”

He was not

jesting.

One of the first physicians

in the

state, taking a fancy to me, had offered to board me,

clothe me, educate me in his profession, and become as a

father to me, if I were willing to accept the kind offices at

his hands.

I could

scarcely realize the verity of what I had heard,

yet ’twas true, and the ensuing new-year beheld me an

inmate of the office of my benefactor.

He is now in

his grave. Stricken down a soldier of

humanity at his post, ere the meridian of life was

reached. Living, he was called the widow’s and orphan’s

friend, and the tears of all attested, at his death, that the

proud distinction was undenied. I am not much, yet what I

am he made me; and when my heart fails to thrill in

gratitude at the silent breathing of his name, may it be

cold to the loudest tones of life.

Behold me,

then, a student of medicine, but yesterday a

cotton-picker; illustrating within my own person, in the

course of a few years, the versatility of American pursuits

and character.

I was scarcely

sixteen, yet I was a student of medicine,

and had been, almost a printer, a cotton-picker, plough-boy,

gin-driver, gentleman of leisure, cabin-boy, cook,

scullion, and runaway, all distinctly referable to the young

lady before-mentioned wearing “No. 2’s,” when her foot

required “fives.”

GETTING ACQUAINTED WITH THE MEDICINES.

“Now, Mr.

Tensas,” said my kind

preceptor, a few days

after I had got regularly installed in the office, “your first

duty must be to get acquainted with the different medicines.

This is a

Dispensatory

— as you read of a drug you will

find the majority mentioned on the shelves, take it down

and digest” — here, unfortunately for the peace of mind and

general welfare of a loafing Indian, who hung continually

around the office, seeking what he might devour, or rather

steal, the doctor was called away in a great hurry, and did

not have time to finish his sentence, so “take it down and

digest,” were the last words that remained in my mind.

“Take it down and digest.” By

the father of physic, thought

I, this study of medicine is not the pleasant task I

anticipated — rather arduous in the long run for the

stomach, I should judge, to swallow and digest all the

medicines, from Abracadabra to Zinzibar. Why, some of

them are

vomits, and I’d like to know how they are to be

kept down long enough to be digested. Now, as for

tamarinds, or liquorice, or white sugar, I might go them, but

aloes, and rhubarb, and castor-oil, and running your finger

down your throat, are rather disagreeable any way you can

take them. I’m in for it, though; I suppose it’s the way all

doctors are made, and I have no claims to be exempted; and

now for the big book with the long name.

I opened it

upon a list of the metals. Leading them in

the order that alphabetical arrangement entitled it to, was,

“Arsenic: deadly poison. Best preparation, Fowler’s

Solution.

Symptoms from an overdose, burning in the stomach, great

thirst, excessive vomiting,” &c., &c. With eyes

distended

to their utmost capacity, I read the dread enumeration of its

properties. What! take this infernal medicament down,

digest it, and run the chances of its not being an overdose?

Can’t think of it a moment. I’ll go back to my plough first;

but then the doctor knew all the dangers when he gave his

directions, and he was so precise and particular, there

cannot be any mistake. I’ll take a look at it anyhow, and I

hunted it up. As the Dispensatory preferred Fowler’s

Solution, I selected that. Expecting to find but a small

quantity, I was somewhat surprised when I discovered it in

a four-gallon bottle, nearly full. I took out the stopper, and

applied it cautiously to my nose. Had it not been for the

label, bearing, in addition to the name, the fearful word

“Poison,” and the ominous skull and cross-bones, I would

have sworn it was good old Bourbon whiskey. Old Tubba,

the Indian, was sitting in the office door, watching my

proceedings with a great deal of interest. Catching the

spirituous odour of the arsenical solution, he rose up and

approached me eagerly, saying, “Ugh; Injun want whiskey;

give Tubba whiskey; bring wild duck, so many,” holding up

two of his fingers. The temptation was strong, I must

confess. The medicines had to be tested, and I felt very

much disinclined to depart this life just then, when the pin

feathers of science had just commenced displacing the soft

down of ducklingdom; but this Indian, he is of no earthly

account or use to any one; no one would miss him, even

were he to take an overdose; science often has demanded

sacrifices, and he would be a willing one; but — it may kill

him; I can’t do it; to kill a man before I get my diploma will

be murder; a jury might not so pronounce it, but conscience

would; I can’t swallow it, and Tubba must not. These

were the thoughts that flashed through my mind before I

replied to the Indian’s request. “Indian can’t have

whiskey. Tubba drink whiskey — Tubba do so.” Here I

endeavoured to go through the pantomime of dying, as I

was not master of sufficient Choctaw to explain myself. I

lifted a glass to my mouth and pretended to empty it, then

gave a short yell, clapping my hands over my stomach,

staggering, jerking my hands and feet about, as I fell on

the floor, repeating the yells, then turned on my face and

lay still as though I was dead. But to my chagrin, all this

did not seem to affect the Indian with that horror that I

intended, but on the contrary, he grunted out a series of

ughs, expressive of his satisfaction, saying, “Ugh; Tubba

want act drunk too.”

The dinner hour

arriving, I dismissed old Tubba, and

arranging my toilet, walked up to the dwelling-house, near

half a mile distant, where I was detained several hours by

the presence of company, to whom I was forced to do the

honours, the doctor not having returned.

At length I got

released, and returned to the office,

resolving to suspend my studies until I could have a talk

with my preceptor; for, even on my ignorant mind, the

shadow of a doubt was falling as to whether there might

not be some mistake in my understanding of his language.

Entering the

office, my eyes involuntarily sought the

Solution of Arsenic. Father of purges and pukes, it was

gone! “Tubba, you’re a gone case. I ought to have

hidden it. I might have known he would steal it after

smelling the whiskey; poor fellow! it’s no use to try and

find him, he’s struck a straight line for the swamp; poor

fellow! it’s all my fault.” Thus upbraiding myself for my

carelessness, I walked back into my bedroom. And my

astonishment may be imagined, when I discovered the

filthy Indian tucked in nicely between my clean sheets.

To all

appearances he was in a desperate condition, the

fatal bottle lying hugged closely in his embrace, nearly

empty. He must be suffering awfully, thought I, when

humanity had triumphed over the indignation I felt at the

liberties he had taken, but Indian-like, he bears it without a

groan. Well has his race been called “the stoics of the

wood, the men without a tear.” But I must not let him die

without an effort to save him. I don’t know what to do

myself, so I’ll call in Dr.B., and away I posted; but Dr. B.

was absent; so was Dr. L.; and in fact every physician of

the town. Each office, however, contained one or more

students; and as half a loaf is better than no bread, I

speedily informed them of the condition of affairs, and

quickly, like a flock of young vultures, we were thronging

around the poisoned Indian, to what we would soon have

rendered the harvest of death.

“Stomach pump

eo instanti!” said one; “Sulphas Zinci

cum Decoction Tabacum!” said another; “Venesection!”

suggested a third. “Puke of Lobelia!” suggested a young

disciple of Thompson, who self-invited had joined the

conclave, “Lobelia. Number six, pepper tea, yaller

powders, I say!” “Turn him out! Turn him out! What right

has young Roots in a mineral consultation? Turn him

out!” — and heels over head, out of the room, through the

middle door, and down the office steps, went “young

Roots;” impelled by the whole body of the enraged

“regulars” — save myself, who, determined amidst the array

of medical lore not to appear ignorant, wisely held my

tongue and rubbed the patient’s feet with a greased rag.

Again arose the jargon of voices.

“Sulphas

Zinci — Stomach, Arteri, pump, otomy-must — legs — hot-toddy — to

bleed him — lectricity — hot blister —

flat-irons — open his — windpipe;” but still I said never a

word, but rubbed his feet, wondering whether I would ever

acquire as much knowledge as my fellow students showed

the possession of. By the by, I was the only one that was

doing anything for the patient, the others being too

busy discussing the case to attend to the administration of

any one of the remedies proposed.

“I say

stimulate, the system is sinking,” screamed a tall,

stout-looking student, as the Indian slid down towards the

foot of the bed.

“Bleeding

is

manifestly and clearly indicated,” retorted

a bitter rival in love as well as medicine, “his muscular

action is too excessive,” as Tubba made an ineffectual

effort to throw his body up to the top of the mosquito bar.

“Bleeding would

be as good as murder,” said Number 1.

“Better cut his

throat than stimulate him,” said Number 2.

“Pshaw!”

“Fudge!”

“Sir!”

“Fellow!”

“Fool!”

“Liar!”

Vim! Vim! and

stomach-pump and brandy bottle flashed

like meteors.

“Fight! fight!

form a ring! fair play!”

“You’re holding

my friend.”

“You lie! You

rascal!”

Vim! Vim! from

a new brace of combatants.

“He’s gouging

my brother! I must help! foul play!”

“Let go my

hair!” Vim! Vim! and a triplet went at it.

I stopped

rubbing, and looked on with amazement. “Gentlemen, this is

unprofessional! ’tis undignified! ’tis

disgraceful! stop, I command you!” I yelled, but no one

regarded me; some one struck me, and away I pitched into

the whole lot promiscuously, having no partner, the

patient dying on the bed whilst we were studying out his case.

“Fight! fight!”

I heard yelled in the street, as I had

finished giving a lick all round, and could hardly keep

pitching into the mirror to whip my reflection, I wanted a

fight so bad.

“Fight! fight!

in D——’s back office!” and here came the

whole town to see the fun.

“I command the

peace!” yelled Dick Locks; “I’m the

mayor.”

“And I’m the

hoss for you!” screamed I, doubling him

up with a lick in the stomach, which he replied to by laying

me on my back, feeling very faint, in the opposite corner

of the room.

“I command the

peace!” continued Dick, flinging one

of the combatants out of the window, another out of the

door, and so on alternately, until the peace was preserved

by nearly breaking its infringers to pieces.

“What in the

devil, Mr. Tensas, does this mean?” said

my preceptor, who at that moment came in; “what does all

this fighting, and that drunken Indian lying in your bed,

mean? have you all been drunk?”

“He has

poisoned himself, sir, in my absence, with the

solution of arsenic, which he took for whiskey; and as all

the doctors were out of town, I called in the students, and

they got to fighting over him whilst consulting;” I replied,

very indignantly, enraged at the insinuation that we had

been drinking.

“Poisoned with

solution of arsenic, ha! ha! oh! lord!

ha!” and my preceptor, throwing his burly form on the floor,

rolled over and over, making the office ring with his

laughter — “poisoned, ha! ha!”

“Get out of

this, you drunken rascal!” said he to the

dying patient, applying his horse-whip to him vigorously.

It acted a charm: giving a loud yell of defiance, the old

Choctaw sprang into the middle of the floor.

“Whoop !

whiskey lour! Injun big man, drunk heap.

Whoop! Tubba big Injun heap!” making tracks for the

door, and thence to the swamp.

The truth must

out. The boys had got into the habit of

making too free with my preceptor’s whiskey; and to keep

off all but the knowing one, he had labelled it, “Solution

of Arsenic.”

A TIGHT RACE CONSIDERIN’.

DURING my

medical studies, passed in a small village in

Mississippi, I became acquainted with a family named

Hibbs (a

nom de plume

of course), residing a few miles

in

the country. The family consisted of Mr. and Mrs. Hibbs

and son. They were plain, unlettered people, honest in

intent and deed; but overflowing with that which amply

made up for all their deficiencies of education, namely,

warm-hearted hospitality, the distinguishing trait of

southern character. They were originally from Virginia,

from whence they had emigrated in quest of a clime more

genial, and a soil more productive than that in which their

fathers toiled. Their search had been rewarded, their

expectations realized, and now,

in their old age, though not wealthy in the “Astorian”

sense, still they had sufficient to keep the “wolf from the

door,” and drop something more substantial than

condolence and tears in the hat that poverty hands round

for the kind offerings of humanity.

The old man was

like the generality of old planters, men

whose ambition is embraced by the family or social circle,

and whose thoughts turn more on the relative value of “Sea

Island” and “Mastodon,” and the improvement of

their plantations, than the “glorious victories of Whiggery in

Kentucky,” or the “triumphs of

democracy in Arkansas.”

The old lady

was a shrewd, active dame, kind-hearted

and long-tongued, benevolent and impartial, making her

coffee as strong for the poor pedestrian, with his all upon

his back, as the broadcloth sojourner, with his

“up-country pacer.”

She was a member of the church, as well as

the daughter of a man who had once owned a race-horse:

and these circumstances gave her an indisputable right,

she thought, to “let on all she knew,” when religion or

horse-flesh was the theme. At one moment she would be

heard discussing whether the new

“circus rider,”

(as she

always called him,) was as affecting in Timothy as the old

one was pathetic in Paul, and anon (not anonymous, for

the old lady did everything above board, except rubbing

her corns at supper), protecting dad’s horse from the

invidious comparisons of some visiter, who, having heard,

perhaps, that such horses as Fashion and Boston existed,

thought himself qualified to doubt the old lady’s assertion

that her father’s horse “Shumach” had run a mile on one

particular occasion. “Don’t tell me,” was her never

failing

reply to their doubts, “Don’t tell me ’bout Fashun or

Bosting, or any other beating ’Shumach’ a fair race, for

the thing was unfesible; did’nt he run a mile a minute

by Squire Dim’s watch, which always stops ’zactly at

twelve, and did’nt he start a minute afore, and git out, jes as

the long hand war givin’ its last quiver on ketchin’ the short

leg of the watch? And didn’t he beat everything in

Virginny ’cept once? Dad and the folks said he’d beat then,

if young Mr. Spotswood hadn’t give ’old Swaga,’

Shumach’s rider, some of that ’Croton water,’ (that them

Yorkers is makin’ sich a fuss over as bein’ so good, when

gracious knows, nothin’ but what the doctors call

interconception could git me to take a dose) and jis ’fore

the race Swage or Shumach, I don’t ’stinctly ’member which,

but one of them had to ’let down,’ and so dad’s hoss got

beat.”

The son I will

describe in few words. Imbibing his

parents’ contempt for letters, he was very illiterate, and as

he had not enjoyed the equivalent of travel, was extremely

ignorant on all matters not relating to hunting or plantation

duties. He was a stout, active fellow, with a merry twinkling

of the eye, indicative of humour, and partiality for practical

joking. We had become very intimate, he instructing me in

“forest lore,” and I, in return, giving amusing stories, or,

what was as much to his liking; occasional introductions

to my hunting-flask.

Now that I have

introduced the “

Dramatis Personae

,” I

will proceed with my story. By way of relaxation, and to

relieve the tedium incident more or less to a student’s life, I

would take my gun, walk out to old Hibbs’s, spend a day or

two, and return refreshed to my books.

One fine

afternoon I started upon such an excursion,

and as I had upon a previous occasion missed killing a fine

buck, owing to my having nothing but squirrel shot, I

determined to go this time for the “antlered monarch,” by

loading one barrel with fifteen “blue whistlers,” reserving

the other for small game.

At the near end

of the plantation was a fine spring, and

adjacent, a small cave, the entrance artfully or naturally

concealed, save to one acquainted with its locality. The

cave was nothing but one of those subterraneous washes

so common in the west and south, and called “sink

holes.” It was known only to young H. and myself, and

we, for peculiar reasons, kept secret, having put it in

requisition as the depository of a jug of “old Bourbon,”

which we favoured, and as the old folks abominated

drinking, we had found convenient to keep there, whither

we would repair to get our drinks, and return to the house

to hear them descant on the evils of drinking, and “vow no

’drap,’ ’cept in doctor’s truck, should ever come

on their plantation.”

Feeling very

thirsty, I took my way by the spring that

evening. As I descended the hill o’ertopping it, I beheld

the hind parts of a bear slowly being drawn into the cave.

My heart bounded at the idea of killing a bear, and my

plans were formed in a second. I had no dogs — the house

was distant — and the bear becoming “small by degrees,

and beautifully less.” Every hunter knows, if you shoot a

squirrel in the head when it’s sticking out of a hole, ten to

one he’ll jump out; and I reasoned that if this were true

regarding squirrels, might not the operation of the same

principle extract a bear, applying it low down in the back.

Quick as

thought I levelled my gun and fired, intending

to give him the buckshot when his body appeared;

but what was my surprise and horror, when, instead of a

bear rolling out, the parts were jerked nervously in, and

the well-known voice of young H. reached my ears.

“Murder!

Hingins! h——l and kuckle-burs! Oh! Lordy!

’nuff! — ’nuff! — take him off! Jis let me off this wunst, dad,

and I’ll never run mam’s colt again! Oh!

Lordy! Lordy! all my brains blowed clean out! Snakes!

snakes!” yelled he, in a shriller tone, if possible, “H——l

on the outside and snakes in the sink-hole! I’ll die a

Christian, anyhow,

and if I die before I wake.” and out

scrambled poor H., pursued by a large black-snake.

If my life had

depended on it, I could not have restrained

my laughter. Down fell the gun, and down dropped I

shrieking convulsively. The hill was steep, and over and

over I went, until my head striking against a stump at the

bottom, stopped me, half senseless. On recovering

somewhat from the stunning blow, I found Hibbs upon me,

taking satisfaction from me for having blowed out his

brains. A contest ensued, and H. finally relinquished his

hold, but I saw from the knitting of his brows, that the

bear-storm, instead of being over, was just brewing. “Mr.

Tensas,” he said with awful dignity, “I’m sorry I put into

you ’fore you cum to, but you’re at yourself now, and as

you’ve tuck a shot at me, it’s no more than far I should have

a chance ’fore the hunt’s up.”

It was with the

greatest difficulty I could get H. to bear

with me until I explained the mistake; but as soon as he

learned it, he broke out in a huge laugh. “Oh, Dod busted!

that’s ’nuff; you has my pardon. I ought to know’d you

didn’t ’tend it; ’sides, you jis scraped the skin. I war wus

skeered than hurt, and if you’ll go to the house and beg me

off from the old folks, I’ll never let on you cuddent tell

coppras breeches from bar-skin.”

Promising that

I would use my influence, I proposed

taking a drink, and that he should tell me how he had

incurred his parent’s anger. He assented, and after we had

inspected the cave, and seen that it held no other serpent

than the one we craved, we entered its cool recess,

and H. commenced.

“You see, Doc,

I’d heered so much from mam ’bout her

dad’s Shumach and his nigger Swage, and the mile a

minute, and the Croton water what was gin him, and how

she bleved that if it warn’t for bettin’, and the cussin’ and

fightin’, running race-hosses warn’t the sin folks said it

war; and if they war anything to make her ’gret gettin’

religion and jinin’ the church, it war cos she couldn’t ’tend

races, and have a race-colt of her own to comfort her

’clinin’ years, sich as her daddy had afore her, till she got

me; so I couldn’t rest for wantin’ to see a hoss-race and go

shares, p’raps, in the colt she war wishin’ for. And then I’d

think what sort of a hoss I’d want him to be — a quarter

nag, a mile critter, or a hoss wot could run (fur all mam says

it can’t be did) a whole four mile at a stretch. Sometimes I

think I’d rather own a quarter nag, for the suspense

wouldn’t long be hung, and then we could run up the road

to old Nick Bamer’s cow-pen, and Sally is almost allers out

thar in the cool of the evenin’; and in course we wouldn’t

be so cruel as to run the poor critter in the heat of the day.

But then agin, I’d think I’d rather have a miler, — for the

’citement would be greater, and we could run down the

road to old Wither’s orchard, an’ his gal Miry is frightfully

fond of sunnin’ herself thar, when she ’spects me ’long, and

she’d hear of the race, certain; but then thar war the four

miler for my thinkin’, and I’d knew’d in such case the

’citement would be greatest of all, and you know, too, from

dad’s stable to the grocery is jist four miles, an’ in case of

any ’spute, all hands would be willin’ to run over, even if it

had to be tried a dozen times. So I never could ’cide on

which sort of a colt to wish for. It was fust one, then

t’others, till I was nearly ’stracted, and when mam, makin’

me religious, told me one night to say grace, I jes shut my

eyes, looked pious, and yelled out, ’D—— n it,

go!’ and in ’bout five minutes arter, came near kickin’

dad’s stumak off, under the table, thinkin’ I war spurrin’

my critter in a tight place. So I found the best way was

to get the hoss fust, and then ’termine whether it should

be Sally Bamers, and the cow-pen; Miry Withers, and

the peach orchard; or Spillman’s grocery, with the bald

face.

“You’ve seed my

black colt, that one that dad’s father

gin me in his will when he died, and I ’spect the reason

he wrote that will war, that he might have wun then,

for it’s more then he had when he was alive, for granma

war a monstrus overbearin’ woman. The colt would cum

up in my mind, every time I’d think whar I was to git a

hoss. ’Git out!’ said I at fust — he never could run,

and ’sides if he could, mam rides him now, an he’s too

old for anything, ’cept totin her and bein’ called mine;

for you see, though he war named Colt, yet for the old

lady to call him old, would bin like the bar ’fecting contempt

for the rabbit, on account of the shortness of his

tail.

“Well, thought

I, it does look sorter unpromisin’, but its

colt or none; so I ’termined to put him in trainin’ the

fust chance. Last Saturday, who should cum ridin’ up

but the new cirkut preacher, a long-legged, weakly, sickly,

never-contented-onless-the-best-on-the-plantation-war-cooked-fur-him

sort

of a man; but I didn’t look at him

twice, his hoss was the critter that took my eye; for the

minute I looked at him, I knew him to be the same hoss

as Sam Spooner used to win all his splurgin’ dimes with,

the folks said, and wot he used to ride past our house so

fine on. The hoss war a heap the wuss for age and

change of masters; for preachers, though they’re mity

’ticular ’bout thar own comfort, seldom tends to thar

hosses, for one is privit property and ’tother generally

borried. I seed from the way the preacher rid, that he

didn’t know the animal he war straddlin’; but I did, and

I ’termined I wouldn’t lose sich a chance of trainin’

Colt by the side of a hoss wot had run real races. So that

night, arter prayers and the folks was abed, I and Nigger

Bill tuck the hosses and carried them down to the pastur’.

It war a forty-aker lot, and consequently jist a quarter

across — for I thought it best to promote Colt, by degrees,

to a four-miler. When we got thar, the preacher’s hoss

showed he war willin’; but Colt, dang him! commenced

nibblin’ a fodder-stack over the fence. I nearly cried for

vexment, but an idea struck me; I hitched the critter, and

told Bill to get on Colt and stick tight wen I giv’ the word.

Bill got reddy, and unbeknownst to him I pulled up a

bunch of nettles, and, as I clapped them under Colt’s

tail, yelled, ’Go!’ Down shut his graceful like a steel-trap,

and away he shot so quick an’ fast that he jumpt

clean out from under Bill, and got nearly to the end of

the quarter ’fore the nigger toch the ground: he lit on his

head, and in course warn’t hurt — so we cotched Colt, an’

I mounted him.

“The next time

I said ’go’ he showed that age hadn’t

spiled his legs or memory. Bill ’an me ’greed we could

run him now, so Bill mounted Preacher and we got ready.

Thar war a narrer part of the track ’tween two oaks, but

as it war near the end of the quarter, I ’spected to pass

Preacher ’fore we got thar, so I warn’t afraid of barkin’

my shins.

“We tuck a fair

start, and off we went like a peeled

ingun, an’ I soon ’scovered that it warn’t such an easy

matter to pass Preacher, though Colt dun delightful, we

got nigh the trees, and Preacher warn’t past yet, an’ I

’gan to get skeered, for it warn’t more than wide enuf for

a horse and a half; so I hollered to Bill to hold up, but

the imperdent nigger turned his ugly pictur, and said, ’he’d be

cussed if he warn’t goin’ to play his han’ out.’ I gin him to

understand he’d better fix for a foot-race when we stopt,

and tried to hold up Colt, but he wouldn’t stop. We reached

the oaks, Colt tried to pass Preacher, Preacher tried to pass

Colt, and cowollop, crosh, cochunk! we all cum down like

’simmons

arter frost. Colt got up and won the race; Preacher

tried hard to rise, but one hind leg had got threw the

stirrup, an’ tother in the head stall, an’ he had to lay still,

doubled up like a long nigger in a short bed. I lit on my feet,

but Nigger Bill war gone entire. I looked up in the fork of

one of the oaks, and thar he war sittin’, lookin’ very

composed on surroundin’ nature. I couldn’t git him down till

I promised not to hurt him for disobeyin’ orders, when he

slid down. We’d ’nuff racin’ for that night, so we put up the

hosses and went to bed.

“Next morning

the folks got ready for church, when it

was diskivered that the hosses had got out. I an’ Bill

started off to look for them; we found them cleer off in the

field, tryin’ to git in the pastur’ to run the last night’s race

over, old Blaze, the reverlushunary mule, bein’ along to act

as Judge.

“By the time we

got to the house it war nigh on to

meetin’ hour; and dad had started to the preachin’, to tell

the folks to sing on, as preacher and mam would be ’long

bimeby. As the

passun

war in a hurry, and had been

complainin’ that his creetur war dull, I ’suaded him to put on

uncle Jim’s spurs what he fotch from Mexico. I saddled the

passun’s hoss, takin’ ’ticular pains to let the saddle-blanket

come down low in the flank. By the time these fixins war

threw, mam war ’head nigh on to a quarter. ’We must ride

on, passun,’ I said, ’or the folks ’ll think we is lost.’ So I

whipt up the mule I rid,

the passun chirrupt and chuct to make his crittur gallop,

but the animal didn’t mind him a pie. I ’gan to snicker, an’

the passun ’gan to git vext; sudden he thought of his

spurs, so he ris up, an’ drove them vim in his hoss’s

flanx

till they went through his saddle-blanket, and like to bored

his nag to the holler. By gosh! but it war a quickener — the

hoss kickt till the passun had to hug him round the neck

to keep from pitchin’ him over his head. He next jumpt up

’bout as high as a rail fence, passun holdin’ on and tryin’ to

git his spurs — but they war lockt — his breeches split

plum across with the strain, and the piece of wearin’ truck

wot’s next the skin made a monstrous putty flag as the old

hoss, like drunkards to a barbacue, streakt it up the road.

“Mam war ridin’

slowly along, thinkin’ how sorry she

was, cos Chary Dolin, who always led her off, had sich a

bad cold, an’ wouldn’t be able to ’sist her singin’ to-day. She

war practisin’ the hymns, and had got as far as whar it says,

’I have a race to run,’ when the passun huv in sight, an’ in

’bout the dodgin’ of a diedapper, she found thar war truth in

the words, for the colt, hearin’ the hoss cumin’ up behind,

began to show symptoms of runnin’; but when he heard the

passun holler ’wo! wo!’ to his hoss, he thought it war me

shoutin’ ’go!’ and sure ’nuff off they started jis as the passun

got up even; so it war a fair race. Whoop! git out, but it war

egsitin’ — the dust flew, and the rail-fence appeered strate

as a rifle. Thar war the passun, his legs fast to the critter’s

flanx, arms locks round his neck, face as pale as a rabbit’s

belly, and the white flag streemin’ far behind — and thar war

Mam, fust on one side, then on t’other, her new

caliker

swelled

up round her like a bear with the

dropsy,

the old lady so

much surprized she cuddent ride steady, an’ tryin’ to stop

her colt, but he war too well trained to stop while he heard

’go!’ Mam got ’sited at last, and her eyes ’gan to glimmer

like she seen her daddy’s ghost axin’ ’if he ever trained up

a child or a race-hoss to be ’fraid of a small brush on a

Sunday,’ she commenced ridin’ beautiful; she braced

herself up in the saddle, and began to make calkerlations

how she war to win the race, for it war nose and nose, and

she saw the passun spurrin’ his critter every jump. She

tuk off her shoe, and the way a number ten go-to-meetin’

brogan

commenced givin’ a hoss particular Moses, were a

caution to hoss-flesh — but still it kept nose and nose.

She found she war carryin’ too much weight for Colt, so

she ’gan to throw off plunder, till nuthin’ was left but her

saddle and close, and the spurs kept tellin’ still. The old

woman commenced strippin’ to lighten, till it wouldn’t bin

the clean thing for her to have taken off one dud more; an’

then when she found it war no use while the spurs lasted,

she got cantankerous. ’Passun,’ said she, ’I’ll be cust if it’s

fair or gentlemanly for you, a preacher of the gospel, to

take advantage of an old woman this way, usin’ spurs

when you know she can’t wear ’em —

’taint Christian-like

nuther,’ and she burst into cryin’. ’Wo! Miss Hibbs!

Wo! Stop! Madam! Wo! Your son!’ — he attempted to say,

when the old woman tuck him on the back of the head, and

fillin’ his mouth with right smart of a saddle-horn, and

stoppin’ the talk, as far as his share went for the present.

“By this time

they’d got nigh on to the meetin’-house,

and the folks were harkin’ away on ’Old Hundred,’ and

wonderin’ what could have become of the passun and

mam Hibbs. One sister in a long beard axt another brethren

in church, if she’d heered anything ’bout that New York

preecher runnin’ way with a woman old enough to be his

muther. The brethrens gin a long sigh an’ groaned ’it ain’t

possible! merciful heavens! you don’t

’spicion?’ wen the sound of the the hosses comin’, roused them

up

like a touch of the

agur,

an’ broke off their serpent-talk. Dad

run out to see what was to pay, but when he seed the

hosses so close together, the passun spurrin’, and mam

ridin’ like close war skase whar she cum, he knew her fix in a

second, and ’tarmined to help her; so clinchin’ a sapplin’, he

hid

’hind a stump ’bout ten steps off, and held on for the

hosses. On they went in beautiful style, the passun’s spurs

tellin’ terrible, and mam’s shoe operatin’ ’no small pile of

punkins,’ — passun stretched out the length of two hosses,

while mam sot as stiff and strate as a bull yearling in his

fust fight, hittin’ her nag, fust on one side, next on t’other,

and the third for the passun, who had chawed the horn till

little of the saddle, and less of his teeth war left, and his

voice sounded as holler as a jackass-nicker in an old saw-mill.

“The hosses war

nose and nose, jam up together so

close that mam’s last kiverin’ and passun’s flag had got

lockt, an’ ’tween bleached domestic and striped

linsey made a beautiful banner for the pious racers.

“On they went

like a small arthquake, an’ it seemed like

it war goin’ to be a draun race; but dad, when they got to

him,

let down

with all his might on colt, scarin’ him so bad

that he jumpt clean ahead of passun, beatin’ him by a

neck, buttin’ his own head agin the meetin’-house, an’

pitchin’ mam, like a lam for the sacryfise, plum through the

winder ’mongst the mourners, leavin’ her only garment

flutterin’ on a nail in the sash. The men shot their eyes and

scrambled outen the house, an’ the women gin mam so

much of their close that they like to put themselves in the

same fix.

“The passun

quit the circuit, and I haven’t been home

yet.”

TAKING GOOD ADVICE.

“POOR fellow!

if he had only listened to me! but he

wouldn’t take good advice,” is the trite exclamation of the

worldling when he hears that some friend has cut his

throat, impelled by despair, or has become bankrupt, or

employed a famous physician, or is about to get married, or

has applied for a divorce, or paid his honest debts, or

committed any deprecated act, or become the victim of

what the world calls misfortune; “poor fellow, but he

wouldn’t take good advice.” Take good advice! yes, if I

had obeyed what is called good advice, I would be now in

my grave; as it is, I am still on a tailor’s books, the best

evidence of a man’s being alive.

When I was a

boy my friends were continually chiding

me for my half bent position in sitting or walking, and

since I have become a man the cry is still the same, “Why

don’t you walk straight, Madison? hold up your head.”

Had I obeyed

them, a tree-top that fell upon me whilst

visiting a patient lately, crushing my shoulder and bruising

my back, would have fallen directly upon my head, and

shown, in all probability, the emptiness of earthly things.

This is one instance showing that good advice is not

always best to be taken; but I have another, illustrating my

position still more strongly.

Whilst a

medical student, I was travelling on one of the

proverbially fine and accommodating steamers that ply

between Vicksburg and New Orleans. Before my departure,

the anxious affection of a female friend made her

exact a promise from me not to play cards; but the

peculiarity of the required pledge gave me an opportunity

of fulfilling it to the letter, but breaking it as to the

spirit. “You’ve promised me, Madison, not to play cards whilst

you’re on earth: see that you keep it.” I assured her I

would do so, as it applied only to shore, and when the

boat was on a sand-bar. It was more her friendly solicitude

than any real necessity in my habits, that made her require

the promise, as I never played except on steamboats, and

then only at night, when the beautiful scenery that skirts

the river cannot be seen or admired.

It was a

boisterous night above in the heavens, making

the air too cool for southern dress or nerves, so the cabin

and social hall were densely crowded, not a small

proportion engaged in the mysteries of that science which

requires four knaves to play or practice it. I had not yet sat

down, but showed strong premonitory symptoms of being

about to do so, when my arm was gently taken by an old

friend, who requested me to walk with him into our stateroom.

“Madison,” said the old gentleman, “I want to give

you some good advice. I see you are about to play cards

for money; you are a young man, and consequently have

but little knowledge of its pernicious effects. I speak from

experience; and apart from the criminality of gambling, I

assure you, you will have but little chance of winning in

the crowd you intend playing with: in fact, you are certain

to lose. Now promise me you won’t play, and I shall go to

bed with the satisfaction that I have saved you from harm.”

The charm was laid too skilfully upon me; I would not

promise, for what was I to do in the long nights of present

and future travel? so my old friend gave me up in despair,

and retired to rest, whilst I sought the card-table.

Young and

inexperienced as I was, an unusual strain

of good luck attended me; and when the game broke up at

daylight, I was considerably ahead of the hounds.

I retired to my

state-room to regain my lost sleep, and

soon was oblivious of everything. How long I slept I do

not know: my dreams ran upon the past game; and just as I

held “four aces,” and had seen my opponent’s two

hundred and went him four hundred dollars better, I was

aroused from my slumbers by the confused cries of “Fire!

Back her! Stop her! She’ll blow up when she strikes!” and a

thousand-and-one undistinguishable sounds, but all

indicative of intense excitement and alarm.

Stopping for

nothing, I made one spring from my berth

into the middle of the cabin, alighting on the deserted

breakfast-table, amidst the crash of broken crockery, three

jumps more were taken, which landed me up on the

hurricane-deck, where I found nearly all the passengers,

male and female, assembled in a fearful state of alarm,

preventing by their outcry the necessary orders, for the

preservation of the boat, from being heard. I took in the

whole scene at a glance. I forgot to mention, when I retired

to rest, the wind was blowing to such a degree that every

gust threatened to overset the boat. The captain, who was

a prudent, sensible man, had tied his boat to the shore,

waiting for the storm to subside. After the lapse of a few

hours, a calm having ensued, he cast loose, intending to

proceed on his way; but scarcely had he done so, when

the wind, suddenly increasing, caught the boat, and, in

despite of six boilers and the helm hard down, was carrying

her directly across the Mississippi, towards the opposite

shore, where a formidable array of old “poke-stalks” and

low, bluff banks were eagerly awaiting to impale us upon

the one hand, or knock us into a cocked hat upon the

other. At this time I arrived upon

the scene — the boat was nearly at the shore, the waters

boiling beneath her bows like an infernal cauldron.

Great as was

the danger, there were still some so

reckless as to make remarks upon my unique appearance,

and turn the minds of many from that condition of

religious revery and mental casting up and balancing of

accounts, which the near proximity to death so imminently

required; and certainly I did look queer — no boots, no

coat, no

drawers

— but, lady reader, don’t think my bosom

was false, and I had no subuculus on. “I didn’t have

anything else” on — more truth than poetry, I ween.

Sixteen young ladies, unmindful of danger, ran shrieking

away; fourteen married ones walked leisurely to the stern

of the boat, where the captain had been vainly before

trying to drive them; whilst two old maids stood and

looked at me in unconscious astonishment, wonderful

amazement, and inexpressible surprise.

“Look out!”

rang the shrill voice of the captain; and,

with a dull, heavy thump, the boat struck the bank, jarring

the marrow of every one on board, save myself — for,

just before she struck, I calculated the distance, made my

jump, landed safely, and was snugly ensconced behind a

large log, hallooing for some one to bring me my clothes.

No damage of

consequence, contrary to expectations,

was done our craft; and after digging her out of the bank,

we proceeded on our way, a heavy rain having

succeeded the storm.

I was lying in

my state-room, ruminating sadly over the

pleasureableness of being the laughing-stock of the

whole boat, when my old adviser of the night previous

entered the room, with too much laughter on his face to

make his coming moral deduction of much force.

“You see now,

Madison, the result of not having followed

my advice. Had you been governed by me, the

disagreeable event of the morning would never have

occurred; you would have been in bed at the proper hour,

slept during the proper hours, been ready dressed as a

consequence at the breakfast hour, and not been the

cause of such a mortal shock to the delicacy of so many

delicate females, besides making a d————d unanimous fool

of yourself.”

I said but

little in reply, but thought a great deal. I kept

my room the balance of the trip, sickness being my plea.

I transacted my

business in the city, and chance made

my old adviser and myself fellow-passengers and

roommates again, on our upward trip. Night saw me

regularly at the card-table, and my old friend at nine

o’clock as constantly in bed.

It was after

his bed-hour when we reached Grand Gulf,

where several lady-passengers intended leaving. They

were congregated in the middle of the gentlemen’s cabin,

bringing out baggage and preparing to leave as soon as

the boat landed.

At the landing

a large broad-horn was lazily sleeping,

squatted on the muddy waters like a Dutch beauty over a

warming-pan.

Her steering-oar — the broad-horn’s, not the

beauty’s — instead of projecting, as custom and the law

requires, straight out behind, had swung round, and stood

capitally for raking a boat coming up along side. The

engines had stopped, but the boat had not lost the

impetus of the steam, but was slowly approaching the

broad-horn, when a crash was head — a

state-room door

was burst open, and out popped my ancient comrade,

followed up closely by a sharp stick, in the shape of the

greasy handle of the steering-oar. It passed directly

through my berth, and would undeniably have killed me,

had I been in it.

It was my turn

to exult now. I pulled “Old Advice” out

from under the table, and, as I congratulated him on his

escape, maliciously added, “You see, now, that playing

cards is not totally unattended with good effects. Had I,

agreeably to your advice, been in bed, I would now be a

mangled corpse, and you enjoying the satisfaction that it

was your counsel that had killed me; whilst, on the other

hand, had you been playing, you would have escaped

your fright, and the young ladies from Nankin in all

probability would never have known you slept in a red

bandana.” I made a convert of him to my side; we sat down

to a quiet game, and before twelve that night he broke me

flat.

THE DAY OF JUDGMENT.

EVERY one is

acquainted with the horror that the

presence of the

small-pox,

or the rumour — which is as

bad — of its being in the neighbourhood, excites. A

planter living some thirty or forty miles from where I was

studying, had returned from New Orleans, where he had

contracted, as it afterwards turned out, the measles, but

which, on their first appearance, had been pronounced by

a young, inexperienced physician, who was first in

attendance, an undoubted case of small-pox. The patient

was a nervous, excitable man, and consequently very

much alarmed; wishing further advice, he posted a boy

after my preceptor,

who, desirous of giving me an opportunity of seeing the

disease, took me with him.

The planter

lived near a small town in the interior, now

no more, but which, in the minds of its

projectors

— judging from its lithographed map — was destined to

rival the first cities of the land. The nature of the disease

was apparent in a moment to my preceptor’s experienced

eye; but the excitability and fear of the patient had

aggravated the otherwise simple disease, so that it presensented

some really alarming symptoms.

A liberal

administration of the brandy bottle soon

reassured the patient and moderated the disease, so that

my preceptor, whose presence was urgently demanded at

home, could intrust him to my care, giving me directions

how to treat the case. He left for home, and I strutted

about, proud in the consciousness of being attending

physician. It being my first appearance in that capacity,

you may imagine that the patient did not suffer for want of

attention. I wore the enamel nearly off his teeth by the

friction produced by requiring the protrusion of his tongue

for examination, and examined his abdomen so often to

detect hidden inflammation, that I almost produced, by my

pommelling, what I was endeavouring to discover in the

first place. In despite of the disease and doctor, the case

continued to improve, and I intended leaving in the

morning for home, when the alarm of the small-pox being in

the settlement having spread, I was put in requisition to

vaccinate the good people. Charging a dollar for each