Katherine van Wormer

David W. Jackson III

Charletta Sudduth.

Excerpt — Irene Williams’ Interview.

The Maid Narratives.

Irene Williams, from Springhill, Louisiana (born 1935). Interviewed by David W. Jackson III. “I wish to God I could tell you more, but it’s too painful.”

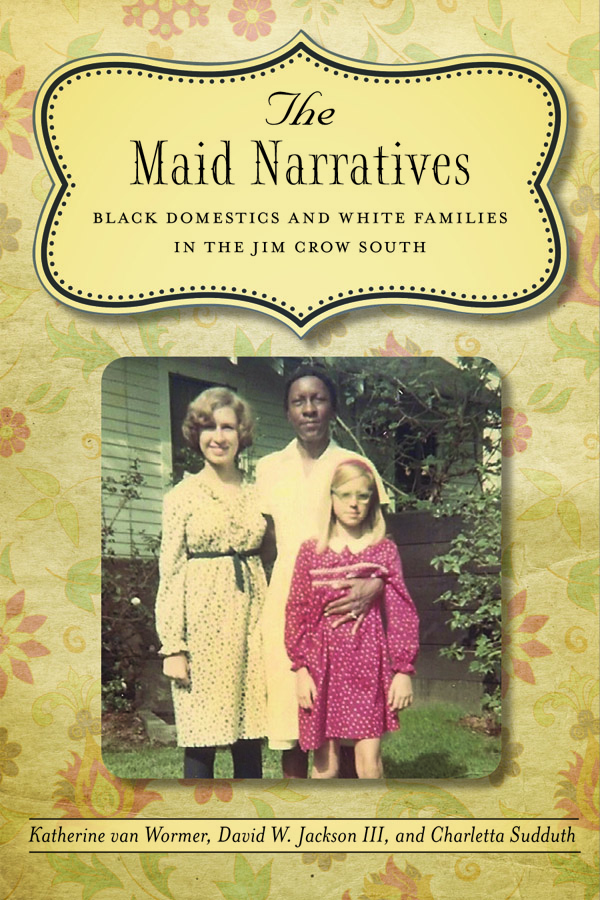

Uniquely among the women interviewed for this project, Mrs. Williams found it very painful to look back. Hers was truly a lost childhood, and today, she mourns the loss deeply. She speaks in a slow voice that is full of sorrow. (See the photo of Mrs. Williams.)

I stayed in Louisiana with my mother until I got grown; then I got married and left. As a child I lived with my auntie for a while, but then I come back home again. See, that’s when we was working in the fields. I was working in the fields when I was twelve years old. You ever plowed a mule?

My mom, she was the one that had the hard time. See, when I was brought up — I didn’t have no father. My father passed away when I was two years old. My mother raised all five of us by herself. And where we were staying, we didn’t have no electricity, no running water in the house. We had a well where we had to draw water. We had our outhouse. And the lamp, we had to put on a lamp, you know. We had to fill up a lamp with coal oil in it; that’s what we did.

My mom worked for white folks. Sometimes she’d take us to our grandmother’s and leave us there. She’d be gone about three or four weeks, away from us because she had to go and work for the white people, she lived with them. And she let us stay with grandmother, her mother.

Interviewer: Let me ask you this. Did you do some domestic work? Did you do some housecleaning, anything like that?

Yeah, for white people. I did housecleaning, cooking, washing clothes, you know, but it had to be perfect, you know. You know how white folks is. Any spot on your clothes is a no-no. You got to get it clean.

The first family I worked for; I don’t remember their names. No, been too long, but they had three kids. I was around sixteen years old. I cooked and I washed their clothes, and I hung them out on the fence. Sometimes the clothes would freeze before I could get them hung out on the fence; it was cold out there.

Interviewer: How about your education?

If you go to school, like if it rains in the morning time, then we’ll go to school then, and at twelve o’clock if it stopped raining and it get dry enough for you to hitch the field, the white man come get you out of school and put you in the field. I work in the field on through the week, on weekends, and need to clean up their house. We didn’t get a chance to go to school. I didn’t get a chance. No, never even know how to read or write.

Interviewer: Well, did any of these people call you any names like use the N word, anything like that?

No, but a lot of others called us that. I remember one day, we was walking to school, me, my brother, and my sister. It had been raining, and there was water all out there, and then they call us niggers. They tried to spit on us and there was nothing we could do; we had to keep walking. When we got home, my mother asked us why we all so wet and we told her and she said, well some people just don’t know how to act right.

Interviewer: So when you were sixteen and having to work all the time, what was that like?

In those days, us colored people had to take what we could get to try to make a living. You never knew if you’d get paid or not. Sometimes they pay us in clothes. You could take it and go; they wasn’t gonna give you no money anyway.

You work in your own clothes. No uniform. You just work. I thought they would call me by my name instead of a maid, but they just called me a maid, saying, “She’s my maid.” And you didn’t go in no white folks front door. You had to go around like when you went to a caf�, all the sudden you had to go to the back.

I remember one day, there was a bunch of stockings. I didn’t think they were no good so I put them in the trash. When the lady come home she ask me, “Well, where are the stockings?” I said, “I thought they had runs and things in them.” “No,” she said. “I put them out there for you to wash them.” I said, “Well, I didn’t know that.” So I had to pay her for the stockings, for some old stockings. That’s the way it was.

They had a big nice house. And they gave you so many chores, so little time to clean, you know, but sometime there’d be two of us — one working the kitchen and one working the bedroom, you know, cleaning. Then when they kids come in, you know by now, white folks don’t care what kids come in their house. They come in, they mess up as you clean it up so you had to go back over, excuse me, and clean it again because they say you didn’t do a good job. You know what I’m saying?

And I remember when I’d go home and tell my mother how they do and she said “Well, baby, do your best.”

Interviewer: Could you use their restroom?

No, never. At that time my brothers had an old car, and if I told them I had to use the restroom they would come and get me and take me home where I could use the restroom, but I had to go back.

No, they didn’t want no colored people using their restroom. And it was tough down there.

Interviewer: Did you have any type of relationship with the wife? You know, like were you friends and you could go to her and talk to her and she would help you?

No. You don’t associate with no white folk down there, not at that time.

Interviewer: How long did you work for this family?

Not long, because my mother stopped me from going there. She said it wasn’t a good idea for me to go there and work and couldn’t use the bathroom. We were just trying to help her because she didn’t have no husband. She didn’t have nothing but us, nobody but us, and we was out there trying to help her.

After that I went to Minden, near Shreveport, to stay with my auntie, and my auntie went to work one day. There was about three or four white guys out in a car, and her next-door neighbor come to her house and told me that the guys wanted someone to work. Well, you know I wanted to work, all we had was work. So I didn’t know no better; so I got in the car and went with him.

Then when we got there, they tell me what to do, but I see all of them standing around one another. You know I don’t know what they were saying. I don’t know what they were planning. I didn’t know what was going on, and it got later and later. I told them, I said, “I gotta go home. My auntie gonna be looking for me.” They said, “What’s the matter, you scared?” I said, “Yeah I am, because I ain’t never been out this late. My auntie don’t like me to be out this late.”

Then they told me, they said, “Well, we have another place you could go and work.” Well, I was thinking what they was gonna do to me, they was gonna try to rape me or do something to me because I don’t know. And I said, “No! I wanna go home.”

I finally got home. And when my auntie found out where I had been, boy, she was pissed. She slapped me down, and she told me, “I know you don’t know, I know you don’t understand, but I’m going to sit down here and tell you.” She told me, she said, “They are too dangerous — a bunch of men. Weren’t no women nowhere, just a bunch of men. Don’t ever get in the car with nobody unless I’m there to go with you. Don’t go nowhere with nobody in no car.”

And later she said to the neighbor, “Don’t never let my niece leave here in a car with a carload of white people. They could hurt her. You don’t know where they was taking her.” I didn’t know where I was going myself.

“Don’t you ever do that again,” she said to me.” I said, “I won’t,” and I didn’t.

Interviewer: Okay, so then, you survived that awful day. You survived that awful day.

I was scared but I made it. Thank God I made it.

Interviewer: Good, okay. So then, you said there were three families? Who was the third person that you worked for? Was there anyone else?

The police. I worked for the police. I worked for him about two or three months. Cleaning. Cooking. Washing. Dusting. Everything you could think of. That’s what I did. The policeman had a little house. Let me see, he had three bedrooms, a living room and a dining room and a kitchen.

He would come home to eat lunch, but his wife she didn’t come to eat lunch, both of them was working, I don’t know where she was working at, but I know he was a policeman because he would come and pick me up in the police car and then he’d take me home in the police car.

He hired me as a cleaning lady. I was paid two dollars an hour, and I worked from seven until four or five that evening.

Interviewer: Did you enjoy the work?

No, because I wasn’t getting paid for what I was doing, but I had to take it because there was nothing nobody could do about it. You take what they gave you.

He never did anything for me. I remember one day I was driving, and another guy ran into the car, and I was trying to tell him about the guy running into my car. And you know what he said, “Oh I heard about that.” That’s all.

Well, the police come to my house one day, and they told me, “You got your license?” and I said “No sir.” And he said, “Well, if you got no license you can’t be driving the car no more.”

Interviewer: Can you say more about what the working conditions were like? Did these people allow you to use the restroom in the house?

Yeah, when they wasn’t there. Then I would clean it back up. See nobody was around where I was working, wasn’t nothing but white people around there, and I couldn’t go to their houses, so I used the restroom there and I cleaned it back up.

No, they didn’t like colored people using their restrooms. I don’t know if they thought we had some type of disease; I don’t know — they didn’t say. They just said we wasn’t allow to use the restroom.

Interviewer: How about other rules in that place?

I couldn’t go through the front door but had to go around through the kitchen door.

Interviewer: Did they allow you to eat at the table with them?

No. I could not eat at the table with no white folk. They not going to have a black person sitting at their table among all the white folks. That’s a disgrace to them. You couldn’t eat. You could prepare, but you could not eat. You ate after they ate.

Interviewer: Would he give you anything extra like food to take home? Maybe for a birthday present or Christmas gift or Christmas bonus? Anything like that?

I — (laughing). I don’t know what that is. It’d be hard to tell you the truth.

Interviewer: Now did he or the other family you worked for, did they ever talk to you about maybe going back to school, getting an education and doing something different?

Are you serious? Only if someone went to school with the white kids. Colored kids, if you was big enough work, you worked. All but the young kids like five or six years old or seven or eight years old wasn’t big enough to work. Other than that we had to work.

Interviewer: Did you learn anything from working for any of these families?

Well, I’ll tell you one thing you can’t take for granted, you got to take what you can get. And I learned what I did, I did it from my heart. What they done, they . . . they got to pay for what they did, not me.

Yeah. That’s what I tell my grandbabies. I don’t like to talk about this, it hurts too much. It brings back all the memories and things you know, what you done and where you come from. It hurts (sounding tearful). I used to sit and look at my mother, and I told her one day, I said, “Mom, when I get grown you won’t have to do this.” But she didn’t make it; she passed away, it was this month. I buried my mother Christmas Day. I don’t like to talk about it.

Interviewer: I understand. . . . I do want to talk about your mother because I think our kids need to hear it. They need to know that the struggles that black people have gone through to get to the point where we are today because our children are a lost generation. They don’t know the history of the struggle so they have a better appreciation of what they have and don’t take it for granted. So your story is compelling. We need it. We need to hear it. People need to know about it, to get them excited about getting an education.

That’s what this is all about. Okay. This is important, very important. We can’t lose this type of history.

It’s a heartache.

Interviewer: Yeah, it happened, it’s a reality. It’s very, very, very real.

And my grandmother, my mother’s mother, she said, “You know I worked for twenty-five cents a day.” That’s all they would give her. And we would sit and listen to her, and she’d say, “Darling, work happens. We were glad to get that twenty-five cents.”

And I said, “What could you do with twenty-five cents, Grandma?” She said, “Honey, you take that twenty-five cents — groceries wasn’t high then — and you get you a sack of potatoes — they was a nickel. I said, “A nickel?” And she said, “Yeah.” She said that twenty-five cents went a long way, and I believed her.

Interviewer: Let’s talk a little bit more about your grandmother. Can you tell me about her?

Her name was Lula Codeman. Grandma told us so many stories, there’s so many of them that I don’t recall. All I know is that she said she used to work for white folks, and she said how they would treat her back then. I don’t remember all these stories.

Interviewer: Okay. What about your mother and what you remember of her work as a cleaning lady?

My mother — they called her a live-in maid because she stayed with the white folks. She left us with our grandmother so she could go off to work. And I remember her coming home, and I was so glad to see my mother. She stayed with us Saturday and Sunday, and she told me, she said, “Baby, Mamma got to leave again.” And I would cry. I didn’t want my mother to leave, but she did. And my grandmother took me into the kitchen as she didn’t want my mother to see me crying and feel sorry because she had to leave me. So I was crying and I didn’t want her to go. And my sisters would say, “Sister, it’s gonna be okay, it’s gonna be okay. Momma be back.” I didn’t want to hear it. I wanted my mother there with me then. But she couldn’t take care there, she had to work.

Interviewer: Now this is important because it shows the sacrifice that had to be made for the mother to provide when the father wasn’t there, that’s what she was doing. Did she at all tell you about the family she worked for and if they were good to her?

She wouldn’t tell us.

Interviewer: And your father, do you remember what happened to him?

Well, I was too young to remember, but they say he fell off a truck and somebody said they pushed him off. I don’t know. I know I growed up without a father.

When my father passed away, Mamma had five kids. She had two girls and three boys. Then she met this other guy. She married him, and she had two girls with him and had five boys with him. But we said that was our whole sister now, we don’t go for that half brother and sister stuff, because we all come from the same mother.

Interviewer: Is there something that we think about the youth today and we hope that — what would you hope that they would learn from your story?

You know sometimes I set up here and I tell my grandbabies how we used to have to do. You know what they tell me? “That was back in the olden days.” I say, “No, Honey, you just don’t understand. This was real.” And I tell them how we were being treated, and they say, “No, I wouldn’t have took it.” But I say, “No, you would have took it, what we did, because there was nothing you could do about it.” The kids today, they think it’s a joke, but it’s no joke, it was real.

I hope they will hear our stories and learn the truth because I don’t want them to go through what we had to go through. I know some of them say they wouldn’t take it, what we had to put up with, but they would have.

I wish to God I could tell you more, but it’s too painful (long pause).

They [the children] don’t believe these things because they don’t see it. They can’t see what you trying to tell them. The think what happened in the olden days is not important to them now.

Interviewer: Now you’ve told about your life and your mother’s life in the South. Was moving to Iowa, your coming here, a way for you to improve your life?

Yeah, because when I was down there I was working for the white people or I was working on the field. Up here the treatment was better. But oh boy, it’s been a long time a coming. I didn’t get up here until the 1970s. My sister-in-law was moving up here so I come up here and stay with them and my sister’s kids, and I never went back.

My aunt was working at Holiday Inn, and she told me I could get a job there; all I had to do was go up there and fill out an application, and that’s what I did. I worked at Holiday Inn. The pay was better, and I was working for black people. And they treated me nice. I stayed there ten years, and then I went to Hotel Fort Des Moines, and I stayed there for seventeen years. That’s where I retired from.

Interviewer: How many children and grandchildren do you have?

I got three kids. My son, he’s fifty. I got a heap of grandkids, but me myself, I got two girls and one son.

Interviewer: So do you think they would be doing better down there or here?

They do better here.

Interviewer: Well, I think we’re good, I think we’re good. We got through all the questions, and you gave me even more information than I thought I was going to get, so this went really good.

I hope so. It was painful, but telling about it helped me get through.

Text prepared by:

- Bruce R. Magee

Source

van Wormer, Katherine, David W. Jackson, III, and Charletta Sudduth. The Maid Narratives: Black Domestic and White Families in the Jim Crow South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 2012. Print. Excerpted from The Maid Narratives by Katherine van Wormer, David W. Jackson, III, and Charletta Sudduth. Copyright © 2012. Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved.