Introduction

Acadian Reminiscences, depicting the True Life of Evangeline, is

a

story centered about the life of the Acadians whose descendants

are now residents of the Teche Country also known as the Land of

Evangeline.

These people lived a pure and simple life with an unbounded

devotion

to their religion and with an unshakable faith in their God. Their

love for one another is unparalleled in the annals of human

history,

to which may be attributed their fortitude and perseverance in

their

travels from Canada, upon being expelled by the British, to their

chosen Land on the banks of Bayou Teche.

The author, Judge Felix Voorhies, relates the story as it was

told to

him by his

grandmother.

The story begins by telling of the native

land

of these

Acadians

and of the village of St. Gabriel from which

they

were driven when the French Province was surrendered to the

British.

It tells of members of the same families being separated and

placed

aboard different ships and some never to see each other again. The

story tells of their landing in Maryland and after some time,

hearing

that members of theirs and other families having landed in

Louisiana.

This news brought encouragement and determination, in face of

great

dangers, to travel to the beautiful Land of the Teche.

The author was best able to present this story as it was handed

down

to him by word of mouth by his grandmother who

adopted Evangeline

when orphaned at an early age. The writer repeats the story in a

simple narrative manner characteristic of the Acadians.

To this day travelers may visit the quaint town of St.

Martinsville on

the banks of Bayou Teche and pay their respects at the grave

shrine of

Evangeline and for a few fleeting moments live the life of these

early

settlers.

Because of the demands for this story and in tribute to Judge

Felix

Voorhies, my grandfather, a man of noble character, staunch

patriotism

and unerring judgment, I, together with all members of the

Voorhies

family, dedicate this book.

FELIX BIRNEY

VOORHIES.

Chapter One

Acadian

Reminiscences

With the true

Story of Evangeline

t seems but yesterday, and yet sixty

years have passed away since my

boyhood. How fleeting is time, how swiftly does old age creep upon

us

with its infirmities. The curling smoke, dispelled by the passing

wind, the water that glides with a babbling murmur in the gentle

stream, leave as deep a mark of their passage as do the fleeting

days

of man.

t seems but yesterday, and yet sixty

years have passed away since my

boyhood. How fleeting is time, how swiftly does old age creep upon

us

with its infirmities. The curling smoke, dispelled by the passing

wind, the water that glides with a babbling murmur in the gentle

stream, leave as deep a mark of their passage as do the fleeting

days

of man.

I was twelve years old, and yet I can picture in my mind the

noble

simplicity of my father’s house. The homes of our fathers were not

showy, but their appearance was smiling and inviting; they had

neither

quaintness nor gaudiness, but were as grand in

their simplicity as

the boundless hospitality of their owners, for no people were more

generous or hospitable than the Acadians who settled in the

magnificent and poetical wilds of the Teche country.

My father’s house stood on a sloping hill, in the center of a

large

yard, whose finely laid rows of china trees, interspersed with

clusters of towering oaks, formed delightful vistas. On the

declivity

of the hill the orchard displayed its wealth of orange, of plum

and

peach trees. Farther on was the garden, teeming with vegetables of

all

kinds, sufficient for the need of a whole village.

I can yet picture that yard, with its hundreds of poultry, so

full of

life, running with flapping of wings and with noisy cacklings

around

my mother as she scattered the grain for them morning and evening.

At the foot of the hill, extending to the Vermillion Bayou, were

the

pasture grounds, where grazed the cattle, and where the

bleating

sheep followed, step by step, the stately ram with tinkling bell

suspended to his neck. How clearly is that scenery pictured in my

mind

with its lights and shadows! Were I a painter I could even now

portray

with striking reality the minutest shadings and beauties of that

landscape.

How strange that I should recall so vividly those things, while

scenes

that I have admired in my maturer years have been obliterated from

my

memory! Ah! the child’s mind, like soft wax, is easily molded to

sensations and impressions that never fade, while man’s mind,

blunted

by the keenness of life’s deceptions, can no longer receive and

retain

the imprints of those impressions and sensations.

If this be true, does not a kind Providence suggest to us, in

this

wise, the wisdom of molding the child’s mind and intelligence with

the

fostering care of parental solicitude, that he may become an

upright

man, a good citizen and a reproachless husband and father.

My father was an Acadian, son of an Acadian, and proud of his

ancestry. The term Acadian was, in those days, synonymous with

honesty, hospitality and generosity. By his indomitable energy, my

father had acquired a handsome fortune, and such was the

simplicity of

his manners, and such his frugality, that he lived, contented and

happy, on his income.

Our family consisted of my father and mother, of three children,

and of my grandmother, a centenarian, whose clear and lucid memory

contained a wealthy mine of historical facts that an antiquarian

or

chronicler would have been proud to possess.

In the cold winter days the family assembled in the hall, where a

goodly fire blazed on the hearth, and while the wind whistled

outside,

our grandmother, an exile from Acadia, would relate to us the

stirring

scenes she had witnessed when her people were

driven from their homes

by the British, their sufferings during their long pilgrimage

overland

from Maryland to the wilds of Louisiana, the dangers that beset

them

on their long journey through endless forests, along the

precipitous

banks of rivers too deep to be forded, among hostile Indians, that

followed them stealthily, like wolves, day and night, ever ready

to

pounce upon them and massacre them.

And as she spoke, we drew closer to her, and grouped around her

and

stirred not, lest we lose one of her words.

When she spoke of Acadia, her face brightened, her eyes beamed

with a

strange brilliancy, and she kept us spellbound, so eloquent and

yet so

sad were her words, and then tears trickled down her aged cheeks

and

her voice trembled with emotion. Under our father’s roof she

lacked

none of the comforts of life. We knew that her children vied with

each

other to please her, and we wondered why it was that

she seemed to be

sad and unhappy. We were then mere children and knew nothing of

the

human heart, grim experience had not taught us its sorrowful

lessons,

and we knew not that a remembrance has often the bitterness of

gall,

and that tears alone will wash away that bitterness.

She sat in her rocking chair, with hands clasped on her knees,

her

body leaning slightly forward, her hair, silvered over by age,

could

be seen under the lace of her cap, her dress was neat and

tasteful,

for she always took pride in her personal appearance.

She called us “petiots” meaning “little ones,” and she took

pleasure

in conversing with us. My father remonstrated with her because she

fondled us too much. “Mother,” he would say, “you spoil the

children,”

but she heeded not his words and fondled us the more. These

details

are interesting to none but myself, and I dwell, perhaps, too long

upon them. Alas! I am an old man, reviewing the joys and sorrows

of

my boyhood, and it seems to me that I have become once more a

little

child when I speak of days gone by, and when I recall the memory

of

those I loved so well and who are no more.

I shall now attempt to repeat the story of my grandmother’s

misfortunes, and as she has related it to us time and again.

Chapter Two

My Grandmother’s

Narrative

She Depicts Acadian Manners

and Customs

etiots,” she said, “my native land is

situated far, far away, up

north, and you would have to walk during many months to reach it;

you

would have to cross rivers deep and wide, go over mountains

looming up

thousands of feet, and beneath impending rocks, shadowing yawning

valleys; you would have to travel day and night, in endless

forests,

among hostile Indians, seeking an opportunity to waylay and murder

you.

etiots,” she said, “my native land is

situated far, far away, up

north, and you would have to walk during many months to reach it;

you

would have to cross rivers deep and wide, go over mountains

looming up

thousands of feet, and beneath impending rocks, shadowing yawning

valleys; you would have to travel day and night, in endless

forests,

among hostile Indians, seeking an opportunity to waylay and murder

you.

“My native land is called Acadia. It is a cold and desolate

region

during winter, and snow covers the ground during several months of

the

year. It is rocky, and huge and rugged

stones lie strewn over the

surface of the ground in many places, and one must struggle hard

for a

livelihood there, especially with the poor and meagre tools

possessed

by my people. My country is not like yours, diversified by rolling

and

gentle hills, covered the year round with a thick carpet of green

grass, and where every plant sprouts up and grows to maturity as

if by

magic, and where one may enrich himself easily, provided he fears

God

and is laborious and economical. Yet I grieve for my native land,

with

its rocks and snows, because I have left there a part of my heart

in

the graves of those I loved so well and who sleep under its sod.”

And as she spoke thus, her eyes streamed with tears and emotion

choked

her utterance.

“I have promised to give you an insight into the manners and

customs

of your Acadian ancestors, and to tell you how it was that we left

our

country as exiles to emigrate to Louisiana. I now keep my promise,

and

will relate to you all that I know of our sad history:

“You must know, petiots, that less than a hundred years ago

Acadia was

a French Province, whose people lived contented and happy. The

king of

France sent brave officers to govern the province, and these

officers

treated us with the greatest kindness; they were our arbiters and

adjusted all our differences, and so equitable were their

decisions,

that they proved satisfactory to all. Is it strange, then, that

being

thus situated we prospered and lived contented and happy? Little

did

we then dream of what cruel fate had in store for us.

“Our manner of living in Acadia was peculiar, the people forming,

as

it were, one single family. The province was divided into

districts

inhabited by a certain number of families, among which the

government

parceled out the land in tracts sufficiently large for their

needs.

Those families grouping together formed small villages,

or posts,

under the administration of commandants. No one was allowed to

lead a

life of idleness, or to be a worthless member of the province. The

child worked as soon as he was old enough to do so, and he worked

until old age unfitted him for toil. The men tended the flocks and

tilled the land, and while they plowed the fields, the boys

followed

them step by step, goading on the work-oxen. The wives and

daughters

attended to the household work, and spun the wool and cotton which

they wove and manufactured into cloth with which to clothe the

family.

The old people not over active and strong, like your grandmother,”

she

would add with a smile, “together with the infirm and invalids,

braided the straw with which we manufactured our hats; so that you

see, petiots, we had no drones, no useless loungers in our

villages,

and every one lived the better for it.

“The land allotted to each district was divided into two unequal

parts; the larger portion was set apart as the tillage ground, and

then

parceled out among the different families; and yet the clashing

of interests, resulting from that community of rights, never

stirred

up any contentions among your Acadian ancestors.

“Although poor, they were honest and industrious, and they lived

contented with what little they had, without envying their

neighbors,

and how could it be otherwise? If any one was unable to do his

field

work because of illness, or of some other misfortune, his

neighbors

flew to his assistance, and it required but a few days work, with

their combined efforts to weed his field and save his crop.

“Thus it was that, incited by noble and generous feeling, the

inhabitants of the province seemed to form one single family, and

not

a community composed of separate families.

“These details, petiots, are tedious to you, and you would rather

that

I should tell you stories more amusing and captivating.”

“No, grandmother, we feel more and more interested

in your narrative.

Speak to us of Acadia, your native land, which we already love for

your sake.”

“Petiots,” she said, “I love my Acadia, and you will learn to

love it

also, when you shall have been made acquainted with the worth of

its

honest and noble inhabitants; besides,” added she, with a sad

smile,

“the gloomy and sombre part of my story remains to be told. When

you

shall have listened to it, you will then understand why it is that

I

feel sad and weep, when the remembrances of the past come crowding

in

my heart. But to resume, contiguous to the village ground lay the

pasture grounds, well fenced in, and which were known as the

common.

In these grounds, the cattle of the colonists were kept, and thus

secured in that safe enclosure, our herds increased every year.

Thus

you see, petiots, we lacked none of the comforts of life, and

although

not wealthy, we were not in want, as our wishes were few and

easily

satisfied.

“Plainness and simplicity of manners are the mainsprings of

happiness,

and he that wishes for what he may never have or acquire, must be

miserable, indeed, and worthy of pity. Alas! that this simplicity

of

our Acadian manners should have already degenerated into

extravagance

and folly! Ah! the Acadians are losing, by degrees, the

remembrance of

the traditions and customs of the mother country, the love of gold

has

implanted itself in their hearts, and this will bring no happiness

to

them. Ere you live to be as old as I,” she would say shaking her

head

mournfully, “you will find out that your grandmother is right in

her

prediction.

“In Acadia, as we prized temperance, sobriety and simplicity of

manners more than riches, early marriages were highly favored.

Early

marriages foster the virtues which give to man the only true

happiness, and from which he derives health and longevity.

“No obstacle was thrown in the way of a loving couple

who desired to

marry. The lover accepted by the maiden obtained the ready consent

of

the parents, and no one dreamed of inquiring whether the lover was

a

man of means, or whether the destined bride brought a handsome

dowry,

as we are wont to do nowadays. Their mutual choice proved

satisfactory

to all, and, indeed, who better than they could mate their hearts,

when they alone were staking their happiness on the venture? and,

besides, it is not often that marriages founded on mutual love

turn

out badly.

“The bans were published in the village church, and the old

curate,

after admonishing them of the sacredness of the tie that bound

them

forever, blessed their union, while the holy sacrifice of mass was

being said. Petiots, it is useless for me to describe the marriage

ceremony and the rejoicings attending the nuptials, as you have

witnessed the like here, but I will speak to you of an old Acadian

custom which prevails no more among us, one which we no longer

observe.

“As soon as the marriage of a young couple was determined, the

men of

the village, after having built a cozy little home for them,

cleared

and planted the land parceled out to them; and while they so

generously extended their aid and assistance, the women were not

laggards in their kindness to the bride. To her they made presents

of

what they deemed most necessary for the comfort and utility of her

household, and all this was done and given with honest and willing

hearts.

“Everything was orderly and neat in the home of the happy couple,

and

after the marriage ceremony in the church and the wedding feast at

the

home of the bride’s father, the happy couple were escorted to

their

new home by the young men and the young maidens of the village.

How

genial was the joy that warmed our hearts and brightened our souls

on

these occasions; how noisy and light the gaiety of the young

people;

how unalloyed their merriment and happiness!”

Chapter Three

Rumors of War Disturb

the Peace and Quiet

of the Acadians

hus far, petiots, I have briefly

depicted to you the simple manners

and customs of the Acadians. I will now relate to you what befell

them, and how a cruel war sowed ruin and desolation in their

homes. I

will tell you how they were ruthlessly treated by the English,

driven

away from Acadia, and despoiled of all their worldly goods and

possessions; how they were scattered to the four winds as wretched

exiles, and how the very name of their country was blotted out of

existence. My narrative will not be gay, petiots, but it is meet

and

proper that you should know these things, and that you should

learn

them

from the lips of the witnesses themselves.

hus far, petiots, I have briefly

depicted to you the simple manners

and customs of the Acadians. I will now relate to you what befell

them, and how a cruel war sowed ruin and desolation in their

homes. I

will tell you how they were ruthlessly treated by the English,

driven

away from Acadia, and despoiled of all their worldly goods and

possessions; how they were scattered to the four winds as wretched

exiles, and how the very name of their country was blotted out of

existence. My narrative will not be gay, petiots, but it is meet

and

proper that you should know these things, and that you should

learn

them

from the lips of the witnesses themselves.

“It was on a Sunday, I remember this as if it were but yesterday,

we

were attending mass, and when our old curate ascended his pulpit,

as

he was wont to do every Sunday, he announced to us that war was

being

waged between France and England. ‘My children,’ said he in sad

and

solemn tones, ‘you may expect to witness awful scenes and to

undergo

sore trials, but God will not forsake you if you put your trust in

his

infinite mercy’; and then kneeling down, he prayed aloud for

France,

and we all responded to his fervent voice, and said amen! from the

depths of our hearts. A painful silence prevailed in the little

church

until mass was over; it seemed as if every one of us was attending

the

funeral of a member of his family. As we left the church, the

people

grouped themselves on all sides to discuss the sad news. There was

no

dancing on the greensward in front of the little church that day,

petiots, and we retired mournfully and quietly to our homes.

“This intelligence troubled us, and we tried, in vain, to shake

off

the gloom that darkened our souls. When we conversed together, the

words died on our lips, and our smiles had the sadness of a sob.

“Ah! Petiots, war, with its train of evils and of woes, is always

a terrible scourge, and it was but natural that we should ponder

mournfully on its consequences and dread the future. England had

enlisted hundreds of Indians in her armies, and we knew that the

bloodthirsty savages spared no one, and inflicted the most

exquisite

tortures on their prisoners; they dreamed of nothing but

incendiarism

and massacre, and these were the troops that were to be let loose

upon

us. The mere thought of facing such fiends, was enough to dismay

the

stoutest heart and to disturb the peace and quiet of a community

like

ours. We knew not what to resolve, but, come what may, we were

determined to die, rather than become traitors to our

King and to our

God.

“Then we argued ourselves into a different mood by thinking that

this

news might, after all, be exaggerated, and that our apprehensions

were

unfounded. Why should England wage war upon us? Acadia, so poor,

so

desolate, so sparsely peopled, was surely not worth the shedding

of a

single drop of blood for its conquest. The storm would pass by

without

even ruffling our peace and tranquillity. We argued thus to rid

ourselves of the gloomy forebodings that troubled us, but despite

our

endeavors, our fears haunted us and made us despondent and

miserable.

“The news that reached us, now and then, were far from being

encouraging. France, whelmed in defeat, seemed to have abandoned

us,

the English were gaining ground, and our Canadian brothers were

calling for assistance. Several of our young men resolved to join

them

to fight the battles of France and to die for their country, if

God so

willed it.

“Ah! Petiots, that was a sad day in the colony, and we all shed

bitter

tears. The brave young men that were sacrificing their lives so

nobly,

wept with us, but remained as firm as rocks in their resolve. We

had,

at last, realized the fact that the threatening ruin was frowning

upon

us, and that it had struck at our very hearts.

“On the day of their departure, the noble young men received the

holy

communion, kneeling before the altar, and they listened to the

encouraging words of the old curate, while every one wept and

sobbed

in the little church. After having told them to serve the king

faithfully and to love God above all else, he gave them his

blessing,

while big tears rolled down his cheeks. Alas! how could he look

upon

them without emotion and grief? He had christened them when they

were

mere babes; he had watched them grow to manhood; he knew them as I

know you, and they were leaving their homes and those that they

loved,

never, perhaps to return.

“They departed from St. Gabriel, sad but resolute, and as far as

they

could be seen, marching off, they waved their handkerchiefs as a

last

farewell. It was a cruel day to us, and from that moment,

everything

grew from bad to worse in Acadia.”

Chapter Four

Threatening Clouds Overcast the

Acadian Sky

The Elders of the Colony Meet in Council

to Discuss the Situation

ix months passed away without our

receiving the least intelligence

of what had become of our brave young men. This contributed, not a

little, to increase our uneasiness, and to sadden our thoughts,

for we

felt in our hearts that they would never return. Our forebodings

proved too well founded,” said my grandmother, with faltering

voice,

“we have never ascertained their fate. We knew, however, that the

war

was still progressing, and that the French were losing ground

every

day. The English directed all their efforts against Canada, and

seemed

to have lost sight of Acadia in the turmoil and fury of battle.

In

spite of our anxiety and apprehensions, the peace and quiet of the

colony remained unruffled. Alas! we had been lulled to security by

deceitful hopes, and the storm that had swept along Canada, was

about

to burst upon us with unchecked fury. Our day of trial had dawned,

and, doomed victims of a cruel fate, we were about to undergo

sufferings beyond human endurance, and to experience unparalleled

outrages and cruelties.”

ix months passed away without our

receiving the least intelligence

of what had become of our brave young men. This contributed, not a

little, to increase our uneasiness, and to sadden our thoughts,

for we

felt in our hearts that they would never return. Our forebodings

proved too well founded,” said my grandmother, with faltering

voice,

“we have never ascertained their fate. We knew, however, that the

war

was still progressing, and that the French were losing ground

every

day. The English directed all their efforts against Canada, and

seemed

to have lost sight of Acadia in the turmoil and fury of battle.

In

spite of our anxiety and apprehensions, the peace and quiet of the

colony remained unruffled. Alas! we had been lulled to security by

deceitful hopes, and the storm that had swept along Canada, was

about

to burst upon us with unchecked fury. Our day of trial had dawned,

and, doomed victims of a cruel fate, we were about to undergo

sufferings beyond human endurance, and to experience unparalleled

outrages and cruelties.”

Our grandmother, at this point, was overcome by her emotion and

hung

her head down. Awed into admiration, mingled with reverence, for

her

noble sentiments and for the ardent love she still cherished for

her

lost country, we gazed upon her in silence, and understood now why

it

was that she always wept when she spoke of Acadia. Having mastered

her

emotions, she brushed away her tears and resumed her narrative as

follows.

“Petiots,” she said in a sweet sad tone, “your grandmother always

weeps when the remembrance of her sufferings and of her

wrongs comes

back to her heart. She is an old woman and her tears soothe her

grief.

Scars of a wounded heart never heal entirely, joy and happiness

alone

leave no trace of their passage, as you shall learn hereafter. But

why

should I speak thus to you? Soon enough you shall learn more from

the

teachings of grim experience, than from all the sayings and

maxims,

how wise and judicious soever they may be.

“It was bruited at St. Gabriel that the English were landing

troops in

Acadia, whence came the rumor, no one could tell, and it would

have

been impossible to trace it to its source, and yet, uncertain as

it

was, it created considerable uneasiness in the community. Bad news

travels fast, petiots, and it looks as if some evil genius took

delight to despatch winged messengers to scatter the tidings

broadcast

over the land. The rumor was confirmed in a manner as tragical as

it

was unexpected.

“One morning, at dawn of day, a young man was lying unconscious

on the

green near the church. His arm was shattered, and he had bled

profusely; it was with the greatest difficulty that we restored

him to

life. When he opened his eyes his looks were wild and terrified,

and,

despite his weakness, he made a desperate effort to rise and flee.

“We quieted him with friendly words, and he heaved a deep sigh of

satisfaction. He had a burning fever, and his parched lips

quivered as

he muttered incoherent words. We removed him to the priest’s

house,

where his wounds were dressed, and when he had recovered from the

exhaustion occasioned by the loss of blood, he related to us what

had

happened to him, and we listened to his words with breathless

suspense

and anxiety.

“‘The English’, said he, ‘have landed troops on the eastern coast

of

Acadia, and are committing the most atrocious cruelties. Their

inhumanity surpasses belief. They pillage and

burn our villages, and

even lay sacrilegious hands on the sacred vessels in our churches.

They tear the wives from their husbands, the children from their

parents, and they drive their ill-fated victims to the seashore,

and

stow them on ships which sail immediately for unknown lands. They

spare only such as become traitors to their Faith and to their

King.

They raided our village at dusk yesterday, and have perpetrated

there

the same wanton outrages and cruelties. They reduced it to ashes,

and

the least expostulation on our part exposed us to be shot down

like

outlaws. They have driven its inhabitants to the seashore like

cattle,

and when through sheer exhaustion, one of their victims fell by

the

road side, I have seen the fiends compel him with the butts of

their

muskets, to rise and walk. I have escaped, in the darkness of

night,

with an arm shattered by a random shot, and I have run exhausted

by

the loss of blood, I fell where you have found me. They will overrun

Acadia,

and they will not spare you, my friends, if you show any

hostility to them. Your town will be raided shortly, and you

cannot

resist them, my friends. Abandon your homes, and seek safety

elsewhere, while you have the time and chance to do so.’

“You may well imagine, petiots, that our trouble was great when

we

heard this terrible news. We stood there, not knowing what to do,

although time was precious, and although it was necessary that we

should devise some plan for our safety and protection. In our

predicament and in so critical an emergency, our only alternative

was

to apply to our old curate for advice.

“He gave us words of encouragement, and withdrew with our elders

to

his room. We remained in the churchyard, grouped together and

speaking

in whispers, our souls harrowed by the most gloomy and despairing

thoughts.

“Ah! Petiots, we often speak of a mortal hour, but the

hour that

passed away while these men were holding counsel in the curate’s

room,

seemed to encompass a year’s duration. Our happiness, our all, our

life itself, in fact, were at stake and turned on their decision,

and

we awaited that decision in dreadful suspense. At last our elders,

accompanied by our old curate, sallied out of that house with

sorrowful countenances, but with steady step and firm resolve

written

on their brows.”

Chapter Five

The Acadians resolve to leave

Acadia as exiles

rather than submit to English rule — Before leaving

St. Gabriel, they apply the torch tothe houses,

and it is swept away by the flames.

heir countenance bespoke the gravity of

the situation, far more

serious, indeed, than we then realized, and as they approached us,

in

the deathlike silence that prevailed, we could distinctly hear the

throbbings of our hearts. We were impatient to learn our fate, and

yet

we dreaded the disclosure. Our anxiety was of short duration, and

one

of our elders spoke as follows. I repeat his very words, for as

they

fell from his lips with the solemn sound of a funeral knell, they

became engraved upon my heart. ‘My good friends,’ said he, ‘our

hopes

were illusory and the future is big with ominous threats

for us. A

cruel and relentless enemy is at our doors. The story of the

wounded

man is true, the English are applying the torch to our villages,

and

are spreading and scattering ruin as they advance. They spare

neither

old age nor infirmity, neither women nor children, and are tender

hearted only to renegades and apostates. Are you ready to accept

these

humiliating conditions, and to be branded as traitors and

cowards?’

heir countenance bespoke the gravity of

the situation, far more

serious, indeed, than we then realized, and as they approached us,

in

the deathlike silence that prevailed, we could distinctly hear the

throbbings of our hearts. We were impatient to learn our fate, and

yet

we dreaded the disclosure. Our anxiety was of short duration, and

one

of our elders spoke as follows. I repeat his very words, for as

they

fell from his lips with the solemn sound of a funeral knell, they

became engraved upon my heart. ‘My good friends,’ said he, ‘our

hopes

were illusory and the future is big with ominous threats

for us. A

cruel and relentless enemy is at our doors. The story of the

wounded

man is true, the English are applying the torch to our villages,

and

are spreading and scattering ruin as they advance. They spare

neither

old age nor infirmity, neither women nor children, and are tender

hearted only to renegades and apostates. Are you ready to accept

these

humiliating conditions, and to be branded as traitors and

cowards?’

“‘Never,’ we answered; ‘never! Rather proscription, ruin and

death.’

“‘My friends,’ he added, ‘exile is ruin; it is despair, it is

desolation. Pause a while and reflect, before forming your

resolve.’

“Not one of us flinched, and without hesitancy, we all cried out:

‘Rather than disown our mother country and become apostates, let

exile, let ruin, let death, be our lot.’

“‘Your answer is noble and generous, my good friends, and your

resolve

is sublime,’ said he; ‘then let exile be our lot.

Many a one has

suffered even more than we shall suffer and for causes less

saintly

than ours. Let us prepare for the worst, for to-day, we bid adieu

forever, perhaps to Acadia, to our homes, to the graves of those

we

loved so well. We leave friendless and penniless for distant

lands; we

leave for Louisiana, where we shall be free to honor and reverence

France, and to serve our God according to our belief. My good

friends,

we barely have the time to prepare ourselves; to-night, we must be

far

from St. Gabriel.’

“These words chilled our hearts. It seemed to us, that all this

was a

dream, a frightful illusion, that clung to our hearts, to our

souls;

and yet, without a tear, without a complaint, we resigned

ourselves to

our fate.

“Ah! it was a cruel day to us, petiots. We were leaving Acadia,

we

were abandoning the homes where our children were born and raised,

we

were leaving as malefactors, without one ray of hope to lighten

our

dark future, and it seemed to us that poor, desolate Acadia was

dearer

to us, now that we were forced to leave her forever. Everything

that

we saw, every object that we touched, recalled to our hearts some

sweet remembrance of days gone by. Our whole life seemed centered

in

the furniture of our desolate homes; in the flowers that decked

our

gardens; in the very trees that shaded our yards. They whispered

to us

ditties of our blithe childhood; they recalled to us the glowing

dreams of our adolescence illumined with their fleeting illusions;

they spoke to us of the hopes and happiness of our maturer years;

they

had been the mute witnesses of our joys and of our sorrows, and we

were leaving them forever. As we gazed upon them, we wept

bitterly,

and in our despair, we felt as if the sacrifice was beyond our

strength. But our sense of duty nerved us, and the terrible ordeal

we

were undergoing did not shake our resolve, and submitting to the

will

of God,

we preferred exile and poverty, with their train of woes and

humiliations, before dishonoring ourselves by becoming traitors

and

renegades.

“In the course of the day our grief increased, and the scenes

that

took place were heart-rending. I never recall them without

shuddering.

“Our people, so meek, so peaceable, became frenzied with despair.

The

women and children wandered from house to house, wailing and

uttering

piercing cries. Every object of spoil was destroyed, and the torch

was

applied to the houses. The fire, fanned by a too willing breeze,

spread rapidly, and in a moment’s time, St. Gabriel was wrapt in a

lurid sheet of devouring flames. We could hear the cracking of

planks

tortured by the blaze; the crash of falling roofs, while the

flames

shot up to an immense height with the hissing and soughing of a

hurricane. Ah! Petiots, it was a fair image of pandemonium. The

people

seemed an army of fiends, spreading ruin and

desolation in their

path. The work-oxen were killed, and a few among us, with the hope

of

a speedy return to Acadia, threw our silverware into the wells.

Oh,

the ruin, the ruin, petiots; it was horrible.

“We left St. Gabriel numbering about three hundred, whilst the

ashes

of our burning houses, carried by the wind, whirled past us like a

pillar of light to guide our faltering steps through the

wilderness

that stretched before us.”

Chapter Six

A Night of Terror and of Misery. The

Exiles are Captured by the

English Soldiery

Driven to the seashore and embarked for deportation—They

are thrown as cast-aways on the Maryland

shores—The hospitality and generosity

of Charles Smith and of Henry Brent

s darkness came, we cast a sad look

toward the spot where our

peaceful and happy St. Gabriel once stood. Alas, we could see

nothing

but the crimson sky reflecting the lurid glare of the flames that

devoured our Acadian villages.

s darkness came, we cast a sad look

toward the spot where our

peaceful and happy St. Gabriel once stood. Alas, we could see

nothing

but the crimson sky reflecting the lurid glare of the flames that

devoured our Acadian villages.

“Not a word fell from our lips as we journeyed slowly on, and as

night

came its darkness increased our misery, and such was our

dejection,

that we would have faced death without a shudder.

“At last we halted in a deep ravine shadowed by projecting rocks,

and

we sat down to rest our weary limbs. We built no fires and spoke

only

in whispers, fearing that the blazing fire, that the

least sound

might betray us in our place of concealment; with hearts failing,

oppressed with gloomy forebodings, the events of the day seemed to

us

a frightful dream.

“Oh! that it only had been a dream, petiots! Alas! it was a sad

reality, and yet in our wretchedness, we could hardly realize that

these events had actually happened.

“Our elders had withdrawn a few paces away from us to decide on

the

best course to pursue, for, in the hurry of our departure, no plan

of

action had been decided upon, our main object being to escape the

outrages and ill-treatment of a merciless and cruel soldiery. It

was

decided to reach Canada the best way we could, after which, after

crossing the great northern lakes, our journey was to be overland

to

the Mississippi river, on whose waters we would float down to

Louisiana, a French colony inhabited by people of our own race,

and

professing the same religious creed as ours.

“But to carry out this plan, petiots, we had to travel thousands

of

miles through a country barren of civilization, through endless

forests, and across lakes as wide and deep as the sea; we were to

overcome obstacles without number and to encounter dangers and

hardships at every step, and yet we remained firm in our resolve.

It

was exile with its train of woes and of misery; it was, perhaps,

death

for many of us, but we submitted to our fate, sacrificing our all

in

this world for our religion, and for the love of France.

“We knelt down to implore the aid and protection of God in the

many

dangers that beset us, and, trusting in His kind Providence, we

lay

down on the bare ground to sleep.

“As you may imagine, petiots, no one, save the little children

slept

that night. We were in a state of mental anguish so agonizing that

the

hours passed away without bringing the sweet repose of a

refreshing

sleep.

“When the moon rose, dispelling by degrees the darkness of night,

we

again pursued our journey. We made the least noise possible as we

advanced cautiously, our fears and apprehensions increasing at

every

step. All at once our column halted; a deathlike silence

prevailed,

and our hearts beat tumultuously within us. Was it the beat of the

drum that had startled us? No one could tell. We listened with

eagerness, but the sound had died away, and the stillness of night

remained undisturbed. Our anxiety became intense. Was the enemy in

pursuit of us? We remained in painful suspense, not knowing what

danger lurked ahead of us. The few minutes that succeeded seemed

as

long as a whole year. We drew close together and whispered our

apprehensions to one another. We moved on slowly, our footsteps

falling noiselessly on the roadway, while we strained our eyes to

pierce the shadows of night to discover the cause of our fears.

The

sound that had startled us was no more heard, and

somewhat

encouraged, our uneasiness grew less.

“We had not advanced two hundred yards when we were halted by a

company of English soldiers. Ah! Petiots, our doom was sealed. We

were

in a narrow path surrounded by the enemy, without the possibility

of

escape. How shall I describe what followed. The women wrung their

hands and sobbed piteously in their despair. The children,

terrified,

uttered shrill and piercing cries, while the men, goaded to

madness,

vented their rage in hurried exclamations, and were determined to

sell

their lives as dearly as possible.

“After a while, the tumult subsided, and order was somewhat

restored.

“The officer in command approached us; ‘Acadians,’ said he, ‘you

have

fled from your homes after having reduced them to ashes; you have

used

seditious language against England, and we find you

here, in the

depth of night, congregated and conspiring against the king, our

liege

lord and sovereign. You are traitors and you should be treated as

such, but in his clemency, the king offers his pardon to all who

will

swear fealty and allegiance to him.’

“‘Sir,’ answered Rene Leblanc, under whose guidance we had left

St.

Gabriel, ‘our king is the king of France, and we are not traitors

to

the king of England whose subjects we are not. If by the force of

arms

you have conquered this country, we are willing to recognize your

supremacy, but we are not willing to submit to English rule, and

for

that reason, we have abandoned our homes to emigrate to Louisiana,

to

seek there, under the protection of the French flag, the quiet and

peace and happiness we have enjoyed here.’

“The officer who had listened with folded arms to the noble words

of

Rene Leblanc, replied with a scowl of hatred: ‘To Louisiana you

wish

to go? To Louisiana you shall go, and seek in vain, under

the French

flag, that protection you have failed to receive from it in

Canada.

Soldiers,’ he added, with a smile that made us shudder, ‘escort

these

worthy patriots to the seashore, where transportation will be

given

them free in his majesty’s ships.’

“These words sounded like a death knell to us; we saw plainly

that our

doom was sealed, and that we were undone forever, and yet, in the

bitterness of our misfortune, we uttered no word of expostulation,

and

submitted to our fate without complaint. They treated us most

brutally, and had no regard either for age or for sex. They drove

us

back through the forest to the seashore, where their ships were

anchored, and stowing the greater number of our party in one of

their

ships, they weighed anchor, and she set sail. The balance of our

people had been embarked on another vessel which had departed in

advance of ours.

“Is it necessary, petiots, that I should speak to you of our

despair

when thus torn from our relatives and friends, when we saw

ourselves

cooped up in the hull of that ship as malefactors? Is it necessary

that I should describe the horror of our plight, our sufferings,

our

mental anguish during the many days that our voyage on the sea

lasted?

“This can be more easily imagined than depicted. We were huddled

in a

space scarcely large enough to contain us. The air rarefied by our

breathing became unwholesome and oppressive; we could not lie down

to

rest our weary limbs. With but scant food, with the water given

grudgingly to us, barely enough to wet our parched lips; with no

one

to care for us, you can well imagine that our sufferings became

unbearable. Yet, when we expostulated with our jailers, and

complained

bitterly of the excess of our woes, it seemed to rejoice them.

They

derided us, called us noble patriots, stubborn French

people and

papists; epithets that went right to our hearts, and added to our

misery.

“At last our ship was anchored, and we were told that we had

reached

the place of our destination. Was it Louisiana? we inquired. Rude

scoffs and sharp invectives were their only answer. We were

disembarked with the same ruthless brutality with which we had

been

dragged to their ship. They landed us on a precipitous and rocky

shore, and leaving us a few rations, saluted us in derision with

their

caps and bidding farewell to the noble patriots, as they called

us.

Our anguish, at that moment, can hardly be conceived. We were

outcasts

in a strange land; we were friendless and penniless, with a few

rations thrown to us as to dogs. The sun had now set, and we were

in

an agony of despair.

“Our only hope rested in the mercy of a kind Providence, and with

hearts too full for utterance, we knelt down with one accord

and

silently besought the Lord of Hosts to vouchsafe to us that pity

and

protection which he gives to the most abject of his creatures.

Never

was a more heartfelt prayer wafted to God’s throne. When we arose,

hope, once more smiling to us, irradiated our souls and dispelled,

as

if by magic, the gloom that had settled in our hearts. We felt

that

none but noble causes lead to martyrdom, and we looked upon

ourselves

as martyrs of a saintly cause, and with a clear conscience, we lay

down to sleep under the blue canopy of the heavens.

“The dawn of day found us scattered in groups, discussing the

course

we were to pursue, and our hearts grew faint anew at the thought

of

the unknown trials that awaited us.

“At that moment, we spied two horsemen approaching our camp. Our

hearts fluttered with emotion. The incident, simple as it was,

proved

to be of great importance to us. We felt as if Providence had

not

forsaken us, and that the two horsemen, heralds of peace and joy,

were

his messengers of love in our sore trials.

“We were not mistaken, petiots. When the cavaliers alighted, they

addressed us in English, but in words so soft and kind, that the

sound

of the hated language did not grate on our ears, and seemed as

sweet

as that of our own tongue. They bowed gracefully to us, and

introduced

themselves as Charles Smith and Henry Brent. ‘We are informed,’

said

they, ‘that you are exiles, and that you have been cast penniless

on

our shores. We have come to greet you, and to welcome you to the

hospitality of our roofs.’ These kind words sank deep in our

hearts.

‘Good sirs,’ answered Rene Leblanc, ‘you behold a wretched people

bereft of their homes and whose only crime is their love for

France

and their devotion to the Catholic faith,’ and saying this, he

raised

his hat, and every man of our party did the same. ‘We thank you

heartily for your greeting and for your hospitality so

generously

tendered. See, we number over two hundred persons, and it would be

taxing your generosity too heavily, no one but a king could

accomplish

your noble design.’

“‘Sir,’ they answered, ‘we are citizens of Maryland, and we own

large

estates. We have everything in abundance at our homes, and this

abundance we are willing to share with you. Accept our offer, and

the

Brent and Smith families will ever be grateful to God, who has

given

them the means to minister to your wants, assuage your afflictions

and

soothe your sorrows.’

“How could we decline an offer so generously made? It was

impossible

for us to find words expressive of our gratitude. Unable to utter

a

single word, we shook hands with them, but our silence was far

more

eloquent than any language we could have used.”

Chapter Seven

Assisted by Their Generous

Friends

The Acadians become prosperous, but yearn to rejoin

their friends and relatives in Louisiana

he same day, we moved to their farms,

which lay near by, and I shall

never forget the kind welcome we received from these two families.

They vied with each other in their kind offices toward us, and

ministered to our wants with so much grace and affability, that it

gave additional charm and value to their already boundless

hospitality.

he same day, we moved to their farms,

which lay near by, and I shall

never forget the kind welcome we received from these two families.

They vied with each other in their kind offices toward us, and

ministered to our wants with so much grace and affability, that it

gave additional charm and value to their already boundless

hospitality.

“Petiots, let the names of Brent and of Smith remain enchased

forever

like precious jewels in your hearts, let their remembrance never

fade

from your memory, for more generous and worthier beings never

breathed

the pure air of heaven.

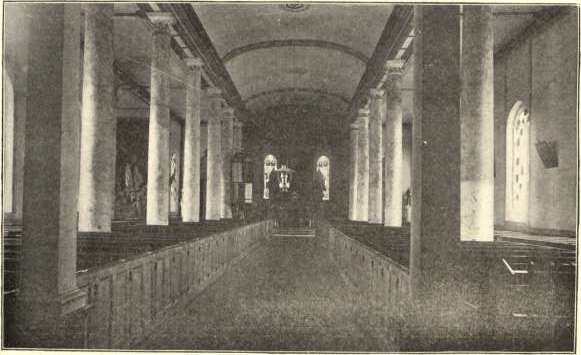

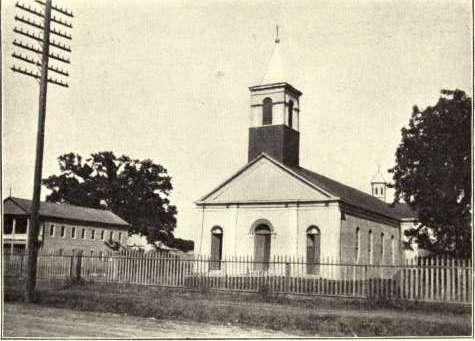

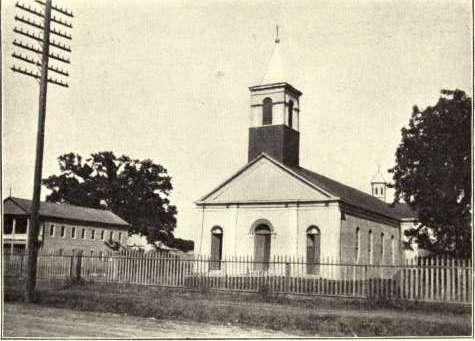

Catholic Church, St. Martinsville, La.

Catholic Church, St. Martinsville, La.

“Thus it was, petiots, that we settled in Maryland after leaving

Acadia.

“Three years passed away peacefully and happily, and during the

whole

of that time, the Smith and Brent families remained our steadfast

friends. Our party had prospered, and plenty smiled once more in

our homes. We lived as happy as exiles could live away from the

fatherland, ignorant of the fate of those who had been torn from

us

so ruthlessly. In vain we had endeavored to ascertain the lot of

our friends and relatives, and what had become of them; we could

learn nothing. Many parents wept for their lost children; many a

disconsolate wife pined away in sorrow and hopeless grief for a

lost husband; but, petiots, the saddest of all was the fate of

poor Emmeline Labiche.”

Emmeline Labiche? Who was Emmeline Labiche? We had never heard

her

name mentioned before, and our curiosity was excited to the

highest

pitch.

Chapter Eight

The True Story

of

Evangeline

mmeline Labiche, petiots, was an orphan

whose parents had died when

she was quite a child. I had taken her to my home, and had raised

her

as my own daughter. How sweet-tempered, how loving she was! She

had

grown to womanhood with all the attractions of her sex, and,

although

not a beauty in the sense usually given to that word, she was

looked

upon as the handsomest girl of St. Gabriel. Her soft, transparent

hazel eyes mirrored her pure thoughts; her dark brown hair waved

in

graceful undulations on her intelligent forehead, and fell in

ringlets

on her shoulders, her bewitching smile, her

slender, symmetrical

shape, all contributed to make her a most attractive picture of

maiden

loveliness.

mmeline Labiche, petiots, was an orphan

whose parents had died when

she was quite a child. I had taken her to my home, and had raised

her

as my own daughter. How sweet-tempered, how loving she was! She

had

grown to womanhood with all the attractions of her sex, and,

although

not a beauty in the sense usually given to that word, she was

looked

upon as the handsomest girl of St. Gabriel. Her soft, transparent

hazel eyes mirrored her pure thoughts; her dark brown hair waved

in

graceful undulations on her intelligent forehead, and fell in

ringlets

on her shoulders, her bewitching smile, her

slender, symmetrical

shape, all contributed to make her a most attractive picture of

maiden

loveliness.

Evangeline

By Edwin Douglas

“Emmeline, who had just completed her sixteenth year, was on the

eve

of marrying a most deserving, laborious and well-to-do young man

of

St. Gabriel, Louis Arceneaux. Their mutual love dated from their

earliest years, and all agreed that Providence willed their union

as

man and wife, she the fairest young maiden, he the most deserving

youth of St. Gabriel.

“Their bans had been published in the village church, the nuptial

day

was fixed, and their long love-dream was about to be realized,

when

the barbarous scattering of our colony took place.

“Our oppressors had driven us to the seashore, where their ships

rode

at anchor, when Louis, resisting, was brutally wounded by them.

Emmeline had witnessed the whole scene. Her lover was carried on

board

of one of the ships, the anchor was weighed, and a stiff

breeze soon

drove the vessel out of sight. Emmeline, tearless and speechless,

stood fixed to the spot, motionless as a statue, and when the

white

sail vanished in the distance, she uttered a wild, piercing

shriek,

and fell fainting to the ground.

“When she came to, she clasped me in her arms, and in an agony of

grief, she sobbed piteously. ‘Mother, mother,’ she said, in broken

words, ‘he is gone; they have killed him; what will become of me?’

“I soothed her grief with endearing words until she wept freely.

Gradually its violence subsided, but the sadness of her

countenance

betokened the sorrow that preyed on her heart, never to be

contaminated by her love for another one.

“Thus she lived in our midst, always sweet tempered, but with

such

sadness depicted in her countenance, and with smiles so sorrowful,

that we had come to look upon her as not of this earth, but rather

as

our guardian angel, and this is why we called her no longer

Emmeline,

but Evangeline, or God’s little angel.

“The sequel of her story is not gay, petiots, and my poor old

heart

breaks, whenever I recall the misery of her fate,” and while our

grandmother spoke thus, her whole figure was tremulous with

emotion.

“Grandmother,” we said, “we feel so interested in Evangeline,

God’s

little angel, do tell us what befell her afterwards.”

“Petiots, how can I refuse to comply with your request? I will

now

tell you what became of poor Emmeline,” and after remaining a

while in

thoughtful revery, she resumed her narrative.

“Emmeline, petiots, had been exiled to Maryland with me. She was,

as I

have told you, my adopted child. She dwelt with me, and she

followed

me in my long pilgrimage from Maryland to Louisiana. I shall not

relate to you now the many dangers that

beset us on our journey, and

the many obstacles we had to overcome to reach Louisiana; this

would

be anticipating what remains for me to tell you. When we reached

the

Teche country, at the Poste des Attakapas, we found there the

whole

population congregated to welcome us. As we went ashore, Emmeline

walked by my side, but seemed not to admire the beautiful

landscape

that unfolded itself to our gaze. Alas! it was of no moment to her

whether she strolled on the poetical banks of the Teche, or

rambled in

the picturesque sites of Maryland. She lived in the past, and her

soul was absorbed in the mournful regret of that past. For her,

the

universe had lost the prestige of its beauties, of its freshness,

of

its splendors. The radiance of her dreams was dimmed, and she

breathed

in an atmosphere of darkness and of desolation.

“She walked beside me with a measured step. All at once, she

grasped

my hand, and, as if fascinated by some vision, she stood

rooted to

the spot. Her very heart’s blood suffused her cheeks, and with the

silvery tones of a voice vibrating with joy: ‘Mother! Mother!’ she

cried out, ‘it is he! It is Louis!’ pointing to the tall figure of

a

man reclining under a large oak tree.

“That man was Louis Arceneaux.

“With the rapidity of lightning, she flew to his side, and in an

ecstacy of joy: ‘Louis, Louis,’ said she, ‘I am your Emmeline,

your

long lost Emmeline! Have you forgotten me?’

“Louis turned ashy pale and hung down his head, without uttering

a

word.

“‘Louis,’ said she, painfully impressed by her lover’s silence

and

coldness, ‘why do you turn away from me? I am still your Emmeline,

your betrothed, and I have kept pure and unsullied my plighted

faith

to you. Not a word of welcome, Louis?’ she said, as the tears

started

to her eyes. ‘Tell me, do tell me that you love me still, and that

the

joy of meeting me has overcome you, and stifled your utterance.’

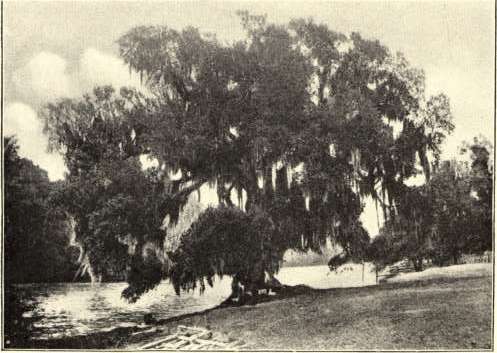

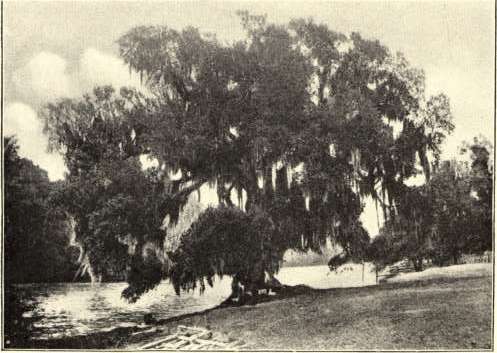

The Evangeline Oak

Near the “Poste des Attakapas”

“Louis Arceneaux, with quivering lips and tremulous voice,

answered:

‘Emmeline, speak not so kindly to me, for I am unworthy of you. I

can

love you no longer; I have pledged my faith to another. Tear from

your

heart the remembrance of the past, and forgive me,’ and with quick

step, he walked away, and was soon lost to view in the forest.

“Poor Emmeline stood trembling like an aspen leaf. I took her

hand; it

was icy cold. A deathly pallor had overspread her countenance, and

her

eye had a vacant stare.

“‘Emmeline, my dear girl, come,’ said I, and she followed me like

a

child. I clasped her in my arms. ‘Emmeline, my dear child, be

comforted; there may yet be happiness in store for you.’

“‘Emmeline, Emmeline,’ she muttered in an undertone, as if to

recall

that name, ‘who is Emmeline?’ Then looking in my face with fearful

shining eyes that made me shudder, she said in a strange, unnatural

voice:

‘Who are you?’ and turned away from me. Her mind was unhinged;

this last shock had been too much for her broken heart; she was

hopelessly insane.

“How strange it is, petiots, that beings, pure and celestial like

Emmeline, should be the sport of fate, and be thus exposed to the

shafts of adversity. Is it true, then, that the beloved of God are

always visited by sore trials? Was it that Emmeline was too

ethereal a

being for this world, and that God would have her in his sweet

paradise? It does not belong to us, petiots, to solve this mystery

and

to scrutinize the decrees of Providence; we have only to bow

submissive to his will.

“Emmeline never recovered her reason, and a deep melancholy

settled

upon her. Her beautiful countenance was fitfully lightened by a

sad

smile which made her all the fairer. She never recognized any one

but

me, and nestling in my arms like a spoiled child, she would give

me

the most endearing names. As sweet and as amiable as

ever, every one

pitied and loved her.

“When poor, crazed Emmeline strolled upon the banks of the Teche,

plucking the wild flowers that strewed her pathway, and singing in

soft tones some Acadian song, those that met her wondered why so

fair

and gentle a being should have been visited with God’s wrath.

“She spoke of Acadia and of Louis in such loving words, that no

one

could listen to her without shedding tears. She fancied herself

still

the girl of sixteen years, on the eve of marrying the chosen one

of

her heart, whom she loved with such constancy and devotion, and

imagining that her marriage bells tolled from the village church

tower, her countenance would brighten, and her frame trembled with

ecstatic joy. And then, in a sudden transition from joy to

despair,

her countenance would change and, trembling convulsively, gasping,

struggling for utterance, and pointing her finger at some invisible

object,

in shrill and piercing accents, she would cry out: ‘Mother,

mother, he is gone; they have killed him; what will become of me?’

And

uttering a wild, unnatural shriek, she would fall senseless in my

arms.

“Sinking at last under the ravages of her mental disease, she

expired

in my arms without a struggle, and with an angelic smile on her

lips.

“She now sleeps in her quiet grave, shadowed by the tall oak tree

near

the little church at the Poste des Attakapas, and her grave has

been

kept green and flower-strewn as long as your grandmother has been

able

to visit it. Ah! petiots, how sad was the fate of poor Emmeline,

Evangeline, God’s little angel.”

And burying her face in her hands, grandmother wept and sobbed

bitterly. Our hearts swelled also with emotion, and sympathetic

tears

rolled down our cheeks. We withdrew softly and left dear

grandmother

alone, to think of and weep for her Evangeline, God’s little

angel.

Chapter Nine

The Acadian leave Maryland

to go to Louisiana

Their perilous and weary journey overland—Death of

Rene Leblanc—They arrive safely in Louisiana

and settle in the Attakapas region on the

Teche and Vermillion Bayous

s I have already told you, petiots,

during three years, we had lived

contented and happy in Maryland, when we received tidings that a

number of Acadians, exiles like us, had settled in Louisiana,

where

they were prospering and retrieving their lost fortunes under the

fostering care of the French government.

s I have already told you, petiots,

during three years, we had lived

contented and happy in Maryland, when we received tidings that a

number of Acadians, exiles like us, had settled in Louisiana,

where

they were prospering and retrieving their lost fortunes under the

fostering care of the French government.

“This news which threw us in a flutter, engrossed our minds so

completely, that we spoke of nothing else. It gave rise to the

most

extravagant conjectures, and the hope of seeing, once more, the

dear

ones torn so cruelly from us, was revived in our hearts.

This news

was deficient, however, in one respect: it left us ignorant of the

fate of those who, like us, had been exiled from St. Gabriel.

“That uncertainty cast a gloom over our hopes which marred our

joy and

happiness, and increased our anxiety.

“Our suspense became unbearable, and we finally discussed

seriously

the expediency of emigrating to Louisiana. The more timid among us

represented the temerity and folly of such an undertaking, but the

desire to seek our brother exiles grew keener every day, and

became so

deeply rooted in our minds, that we concluded to leave for

Louisiana,

where the banner of France waved over true French hearts.

“We announced our determination to our benefactors, the Brent and

Smith families, and, undismayed by the perils that awaited us, and

the

obstacles we had to overcome, we prepared for our pilgrimage from

Maryland to Louisiana.

“Our friends used all their eloquence to dissuade us from our

resolve,

but we resisted all their entreaties, although we were deeply

touched

by this new proof of their friendship. We disposed of the articles

that we could not carry along with us, and kept our wagons and

horses

to transport the women and children, and the baggage. In all, we

numbered two hundred persons, and of these, fifty were well armed,

and

ready to face any danger.

“We journeyed slowly; the wagons moved in the centre, while

twenty men

in advance, and as many in the rear marched four abreast. Ten of

the

bravest and most active of our young men took the lead a short

distance ahead of the column, and formed our advance guard. Our

forces

were distributed in this wise, petiots, for our safety, as the

road

lay through mountain defiles, and in a wild and dreary country

inhabited by Indians.

“We secured, as scouts and guides, two Indians well known to the

Brent

family, and in whom, we were told, we could place the

most implicit

confidence. We had occasion, more than once, to find how fortunate

we

had been to secure their services. We set out on our journey with

sorrow. We were parting with friends kind and generous; friends

who

had relieved us in our needs, and who had proved true as steel,

and

loving as brothers. We were parting from them, lured with hopes

which

might prove illusory, and when we grasped their hands in a last

farewell, words failed us, and our tears and sobs told them of our

gratitude for the benefits they had, so generously, showered upon

us.

They, too, wept, touched to the heart by the eloquent, though

mute,

expression of our gratitude. Their last words, were words of love,

glowing with a fervent wish that our cherished hopes might be

realized.

“We set out in a westerly direction, and we had soon lost sight

of the

hospitable roofs of the Brent and Smith families. We again felt

that

we were, once more, poor wandering exiles roaming

through the world

in search of a home.

“Our journey, petiots, was slow and tedious, for a thousand

obstacles

impeded our progress. We encountered deep and rapid streams that

we

could not cross for want of boats; we traveled through mountain

defiles, where the pathway was narrow and dangerous, winding over

hill

and dale and over craggy steeps, where one false step might hurl

us

down into the yawning chasm below. We suffered from storms and

pelting

rains, and at night when we halted to rest our weary limbs, we had

only the light canvass of our tents to shelter us from the

inclemency

of the weather.

“Ah! petiots, we were undergoing sore trials! But we were lulled

by

the hope that far, far away in Louisiana, our dreamland, we would

find

our kith and kin. That radiant hope illumined our pathway; it

shone as

a beacon light on which we kept our eyes riveted, and it steeled

our

hearts against sufferings and privations almost too

great to be borne

otherwise.

“Thus we advanced fearlessly, aye, almost cheerfully, and at

night,

when we pitched our tents in some solitary spot, our Acadian songs

broke the silence and loneliness of the solitude, and, as the

gentle

wind wafted them over the hills, the light couplets were re-echoed

back to us so clearly and so distinctly, that it seemed the voice

of

some friend repeating them in the distance.

“As long as we journeyed in Virginia, barring the obstacles

presented

by the roads of a country diversified by hill and dale, our

progress,

though slow, was satisfactory. The people were generous, and

supplied

us with an abundance of provisions. But when the white population

grew

sparser and sparser, and when we reached the wild and mountainous

country which, we were told, bore the name of Carolina, then,

petiots,

it required a stout heart and firm resolve, indeed, not to abandon

the

attempt to reach Louisiana by the overland

route we were following.

“During days and weeks, we had to march slowly and tediously

through

endless forests, cutting our way across undergrowth so thick, as

to be

almost impervious to light, brushwood where a cruel enemy might

lay

concealed in ambush to murder us, for we were now in the very

heart

of the Indian country, and the savages followed us, stealthily,

day

and night. We could see them with their tattooed faces and hideous

headgear of feathers, frightful in appearance, lurking around in

the

forest, and watching our movements. We were always on the alert,

expecting an attack at any moment, for we could distinctly hear

their

whoops and fierce yells.

“Ah! Petiots, it was then that our mental and bodily anguish

became

extreme, and that the stoutest heart grew faint under the pressure

of

such accumulated woes. Our nights were sleepless, and, careworn

and on

the verge of starvation, we moved steadily

onward, the very picture

of dejection and of despair. Thus we toiled on day after day, and

night after night, during two long weary months on our seemingly

endless journey, until, disspirited and disheartened, our courage

failed us.

“It was a dark hour, full of alarming forebodings, and we

witnessed

the depression of our brother exiles with sorrow and apprehension.

“But a kind Providence watched over us. God tempereth the wind to

the

shorn lamb. The hope of finding our lost kindred stimulated our

drooping spirits. We had been told that Louisiana was a land of

enchantment, where a perpetual spring reigned. A land where the

soil

was extremely fertile; where the climate was so genial and

temperate,

and the sky so serene and azure, as to justly deserve the name of

Eden

of America. It smiled to us in the distance like the promised

land,

and toward that land we bent our weary steps, longing for the day

when

we would tread its soil, and breathe once more the

pure air in which

floated the banner of France.

“At last we reached the Tennessee river, where it curves

gracefully

around the base of a mountain looming up hundreds of feet. Its

banks

were rocky and precipitous, falling straight down at least fifty

feet, and we could see, in the chasm below, its waters that flowed

majestically on in their course toward the grand old Meschacebe.

It

was out of the question to cross the river there, and we followed

the

roadway on its banks around the mountain, advancing cautiously to

avoid the danger that threatened us at every step.

“That night, we slept in a large natural cave on the very brink

of the

precipice by the river. At dawn of day we resumed our march, and

as we

advanced, the country became more and more level, and after four

days

of toil and fatigue, we halted and camped on a hill by the

riverside,

where a small creek runs into the river. We met

there a party of

Canadian hunters and trappers who gave us a friendly welcome, and

replenished our store of provisions with game and venison. They

informed us that the easiest and least wearisome way to reach

Louisiana was to float down the Tennessee and Meschacebe rivers.

The

plan suggested by them was adopted, and the men of our party,

aided by

our Canadian friends, felled trees to build a suitable boat.

“There, petiots, a great misfortune befell us. We experienced a

great loss in the death of Rene Leblanc, who had been our leader

and

adviser in the hours of our sore trials. Old age had shattered his

constitution, and unequal to the fatigues of our long pilgrimage,

he

pined away, and sank into his grave without a word of complaint.

He

died the death of a hero and of a Christian, consoling us as we

wept

beside him, and cheering us in our troubles. His death afflicted

us

sorely, and the night during which he lay exposed, preparatory

to his

burial, the silence was unbroken, in our camp, save by our

whispered

words, as if we feared to disturb the slumbers of the great and

good

man that slept the eternal sleep. We buried him at the foot of the

hill, in a grove of walnut trees. We carved his name with a cross

over

it on the bark of the tree sheltering his grave, and after having

said

the prayers for the dead, we closed his grave, wet with the tears

of

those he had loved so well.

“My narrative has not been gay, petiots, but the gloom that

darkened

it will now be dispelled by the radiant sunshine of joy and of

happiness.

“Our boat was unwieldy, but it served our purpose well. We stored

in

it our baggage and supplies; we sold our horses and wagons to our

Canadian friends, and taking leave of our Indian guides, we cut

loose

the moorings of the boat. We floated down stream, our young men

rowing, and singing Acadian songs.

“Nothing of importance happened to us after our

embarkment, petiots.

During the day, we traveled, and at night, we moored our boat

safely,

and encamped on the banks of the river. At last we launched on the

turbulent waters of the Mississippi and floated down that noble

stream

as far as Bayou Plaquemines, in Louisiana, where we landed. Once

more

we were treading French soil, and we were freed from English

dominion.

“As the tidings of our arrival spread abroad, a great number of

Acadian exiles flocked to our camp to greet and welcome us. Ah!

petiots, how can I describe our joy and rapture, when we

recognized