/

Louisiana Anthology

John Smith Kendall.

“History of New Orleans.”

Notes to next group

Continue linking the footnotes.

1. Create links under the Author's notes

2. Copy first one, then just change to the corresponding number for footnote

3. Then copy the first link, find each it in the text above, change the N & F along with the link word, then continue by changing the number correspondents and link word.

Chapter IV

Establishment of the Municipal Government

Within less than one hundred years Louisiana had passed through six changes of government. Originally governed directly by the crown, Louis XIV had put it, in 1712, in the hands of Antoine Crozat. In 1717 it had been transferred from Crozat to the Compagnie de l'Occident. The Company ceded it in 1731 back to the Government of France. Spain acquired the country in 1762. In 1801 the king of Spain had relinquished the province to France and now France had sold all of its rights in this vast and fertile domain to the United States.

At the time of the cession, New Orleans had been for thirty-four years under Spanish control. During the early part of this long period, its interests had been neglected, and its progress had been slow. Onzaga, for instance, admitted that, during the first four years, the population had not increased. The increment by birth had been offset by the loss through emigration. But better times followed. The governmental policies underwent certain relaxations; commerce revived, and by 1785 an official census revealed within the walls of New Orleans 4,980 persons, while by 1788 this number grew to 5,338. There was an increase in the first sixteen years of Spanish control of 56 percent , or, in the nineteen years, of 57 percent . Immigration was not encouraged. The growth of the population was due to natural causes. With the exception of some agriculturalists from Malaga, the Canaries, and Nova Scotia; and the American immigration which Spain at first impeded and then fostered, there were very few imported additions to the total number of inhabitants. In 1778, when Galvez required all the English-speaking residents to take an oath of fidelity to Spain, there were but 170 persons affected by his order. The British traders whom O'Reilly had expelled in 1769 gradually returned to the city, or were replaced by others. The trade concessions of 1782 brought to the city some French merchants; their number was augmented a few years later when the French Revolution compelled the Royalists to seek refuge in foreign lands; a respectable contingent sought the shores of the Mississippi. Some Germans and some Italians established themselves, as they naturally would do, in a seaport. The slave-revolt in Santo Domingo in 1791 drove many refugees into New Orleans, amongst whom were the members of the first theatrical troupe that ever played in Louisiana. Nevertheless, the population remained essentially Creole. Outside of official circles there were few Spaniards, and a number of them were identified with the dominant element through marriage.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century New Orleans was reckoned one of the most important of North American seaports. In 1802, 158 American, 104 Spanish, and 3 French vessels — a total of 265 — with an aggregate tonnage of 31,241, sailed from the harbor. In the following year the import tonnage showed an increase of from 35 to 37 percent . Already, along the river-bank just above the city, "within ten steps of Tchoupitoulas Street," the fleets of flatboats and barges from the upper part of the Mississippi Valley were finding a convenient mooring place. In front of the town, near the Place d'Armes, lay the shipping, often twenty or more vessels at a time, made fast to the bank, where "they received and discharged with the same ease as from a wharf." The small tonnage of the individual vessels, and the depth of water made this possible. Below the Place d'Armes was the anchorage of war vessels, visits from which were not frequent.

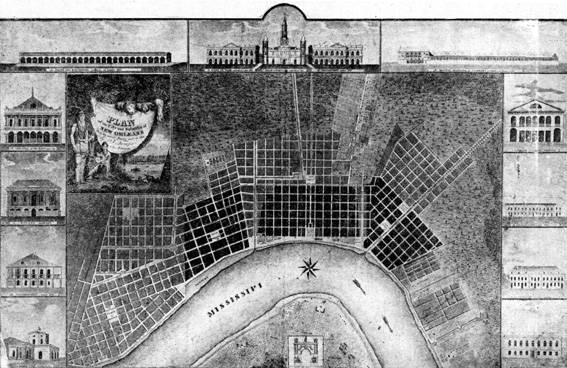

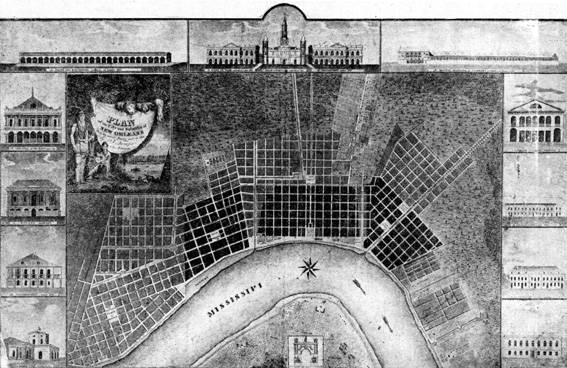

The town had already outgrown its original boundaries. It is estimated that there were from 1,200 to 1,400 separate premises, or about 4,000 roofs of one sort and another. Some of the larger buildings were substantially constructed of brick and roofed with slate. Those on the three or four streets nearest the river were sometimes two or even two and a half stories in height. Those farther back were usually one story high, of wood, roofed with shingles, and often elevated on wooden pillars from eight to fifteen feet above the ground. The homes of the poor were scattered in all parts of the city, but especially on the rear streets. Even among the most prosperous classes there were many whose domiciles were small and rude. In the center of the river-front rose the unfinished cathedral, flanked on the upper side by the arcaded front of the Principal, where the Cabildo had held its stately convocations; and on the lower side by a widespreading wooden building occupied by the priests attached to the cathedral. On either side of the Place d'Armes ran two long rows of one-story buildings, containing the principal retail stores of the town. The Government House, the Barracks, the hospital, the home of the Ursuline nuns, and a few other buildings survived here and there from the first French regime. The streets were straight and tolerably wide, but none of them were paved. In bad weather they were often impassable to vehicles. There were few sidewalks; such as existed were made of wooden planks pegged down to the earth, except in the heart of the town, where there were some narrow brick "banquettes." The streets were not lighted. At night it was a difficult operation to find one's way about. All the refuse of the city found its way into the gutters, which were filthy and emitted an unspeakable stench. Business was concentrated largely on Toulouse, St. Peter, Conti, St. Louis, Royal and Chartres streets along the levee. The French were for the most part content to invest their savings in real estate. They were the proprietors of the retail establishments. They lent money — often at one or two percent per month. The Spanish, who, except for those in Government employ, were mainly Catalans, kept the lesser shops and the cheap drinking places which infested all parts of the town. The wholesale business, in fact, almost all the larger commercial establishments of every description, were in the hands of Americans, English and Irish. In society and politics, however, the conditions were reversed. There the Creole was dominant. Creoles held many important governmental employments; they sought commissions in the military forces; they influenced very largely the government of the city.

Around the "Old Square" — the Vieux Carré — as the original city was called — stretched a line of marshy, grass-covered mounds and fosses — all that remained of the fortifications erected by old Spanish governors, and long since fallen to ruin. Just beyond the tiny Fort St. Ferdinand, which was still maintained in tolerable repair, lay the Carondelet basin, with the canal of that name stretching away through the tropical greenery towards Bayou St. John. Both basin and canal had been neglected for years, and were now so shoal that only small craft could use them. Larger vessels coming in with cattle and farm produce from East and West Florida, as they were then called, could approach the city no nearer than the suburban town of St. Johnsburg, on the bayou. The number of vessels arriving at these points in 1802 was 500. They were mainly of small size, the largest of 50 tons, the majority well under that

figure.

The moral condition was not good. An intelligent French traveler who visited New Orleans at this time has left a lurid picture of the idle, luxurious, dissipated life which he found in the city. Gambling was the almost universal vice of the men. At the numerous games of chance ship agents, ship-masters, planters, travelers, and the leisured classes generally wagered their entire available funds, and, losing, fell into the hands of a hoard of money lenders who infested the city. The presence in the community of a large class of quadroon women was another undesirable feature. The balls at which these attractive, unprincipled persons figured were already notorious. The respectable white women, on the other hand, had few opportunities for social and mental development. Their lives were passed in a monotonous round of household duties, which left them little material for conversation. There was, moreover in all classes, a singular indifference to law and order. The clergy had little influence over their parishioners insofar as the regulation of their daily conduct was concerned. Education was neglected. Aside from the benefits of travel in Europe, which were reserved for the wealthier classes, the opportunities for improvement were few and not much valued. Smuggling was so generally practiced as to be regarded almost as a

profession.

Such, then, in a few of its most striking aspects, was the community which now passed under the control of the United States.

The sentimental regret with which the Creoles had seen the tri-color lowered at the Place d'Armes on the 30th of November, was soon intensified by a variety of circumstances, due to differences of language, usages and habits, as well as to the insolence of some of the American patrols towards the inhabitants. The discretion and firmness of the new governor easily repressed the outward manifestations of this irritation, but he could not immediately change the thoughts and feelings which prompted them. These antagonisms were artfully stimulated by intriguing French and Spanish officials, who lingered in the city for several months, after the cession had put an end to their employments. A captious, irritable spirit resulted, which vented itself in incessant complaints against the individuals who composed the Governor's official family, and especially against the Governor. The starting point of this opposition was probably a fear that annexation to the United States meant the suppression of the slave trade. That trade was "all important to the very existence of the country," as a protesting delegation represented to Congress. It was secretly but persistently carried on through Lakes Borgne, Maurepas and Pontchartrain, and through scores of inlets in the labyrinthine coastline of the gulf, where the channels were indistinguishable from the marshes, and where enterprising but unscrupulous smugglers and buccaneers, like the Lafittes, might easily elude pursuit. Nor were the people pleased to see some of the old Spanish grants nullified, and all titles subjected to official re-inspection.

W. C. C. Claiborne,

First American Governor of Louisiana

From a painting

in the Louisiana State Museum

In part the situation had been prepared in advance of the arrival of the American commissioners by the quarrels that had arisen between Laussat and the Spanish governor Salcedo, and between Laussat and Casa Calvo. As has already been said, these disputes had marshalled the populace into two camps. The long delay which preceded the surrender of the city into Laussat's hands had helped also to irritate the public mind. Now Claiborne was appointed governor of Louisiana with all the powers possessed by both the governor and the Intendant of former times. In other words, he was made the absolute ruler of the land, uniting in himself all executive, judicial and legislative authority — a range and variety of power probably never before or since confided to a single American citizen. His tenure of this despotic power was brief, but, even so, it would have been better had it been still further curtailed. Probably Claiborne's task would have been greatly simplified had Congress immediately created some sort of temporary legislative and judicial authority, some council, or chamber, composed of the best informed men in the city and delegated a part of the governor's too extensive powers to it. Certainly this course would have tended to conciliate the Creoles. Claiborne would himself have made some such arrangement, had he possessed the power.

Laussat, like all revolutionary spirits, was more eager to destroy than to create. With the exception of the new "municipality," he failed to organize new tribunals to replace the Spanish judicial institutions which he suppressed. Yet such were imperatively necessary if the ordinary business of life was to be carried on. Claiborne was compelled to supply the need. He could not reinstitute the courts abolished by Laussat. To do so would have been instantly construed as siding with Casa Calvo and the Spanish faction. At that moment it was not clear that Spain would not dispute the cession of Louisiana to the United States. The Spanish king had registered a protest against the action of the first consul; his minister in Washington had notified the American Government that there existed certain defects in the instrument of alienation which impaired its validity — the chief of which was a solemn promise by France that the territory should never be parted with. It was therefore clearly impossible for Claiborne to allow himself for a moment to be confounded with the intriguing Spanish clique. Unfortunately, however, Claiborne had no specific instructions from the Washington Government as to the procedure to follow in the premises. In taking the course he finally adopted he was guided wholly by his own discretion. He found himself virtually the only person in the community invested with judicial power. The principal, provisional and ordinary alcaldes were all involved in Laussat's suppression of the Cabildo, and disappeared with that institution. Only the "alcaldes de barrio" remained and their usefulness was so limited as to be practically nil. Under the Spanish, the principal jurisdiction in law suits, had, as we have seen, been enjoyed by two "alcaldes," who were annually elected by the Cabildo and who, on election, became members of that body. The Cabildo itself possessed appellate jurisdiction in certain civil suits. The re-establishment of the Spanish tribunals would have necessitated the revival of the Cabildo and the suppression of the new municipality, which was out of the question.

There were other weighty considerations which had to be regarded also. Louisiana was destined to be admitted into the union of American States. Its government had to be assimilated to that of the other American commonwealths as rapidly as circumstances permitted. Claiborne realized that similarity of legal institutions constituted a strong bond of union throughout the United States as it already existed. The differences which had, in fact, existed between the legal customs of France and those of her colonial possessions during the time when Louisiana was under her control, had been deplored by the ablest French jurists and philosophers. It was recognized that these differences constituted a serious weakness in the organization of the colonial governments. If then, these anomalies had proven detrimental under amonarchical form of government, how much more so would they be in a federated community like that of the United States?

But, as a matter of fact, no defense is needed to justify Claiborne in setting up his Court of Pleas. This court was established on December 30, 1803. It consisted of seven justices. Their civil jurisdiction was limited to cases not exceeding $3,000 in value, with the right of appeal to the Governor when the amount in litigation rose above $500. Their criminal jurisdiction extended to all cases where the punishment did not exceed a fine of $200 or imprisonment of more than sixty days. Each individual justice was vested with summary jurisdiction over all cases involving $100 or less, but the parties at interest possessed the right to appeal in all cases to the court itself — that is to say, to the seven justices sitting en banc. This arrangement reserved to the governor original jurisdiction in all civil and criminal matters save as specifically conceded and also appellate jurisdiction over the new tribunal. It had, however, the very great merit of furnishing a method by which the government of the city could be carried on. Without it, the municipality, as constituted by Laussat and temporarily retained in office by Claiborne, was futile.

The Spanish laws were, on the whole, admirable, but the system of executing them was effete and corrupt. Their most objectionable feature was that the judge might hear, examine and decide in secret. Claiborne's new court brought all these operations out into the light; trial by jury was introduced and the judge was amenable to public opinion. But no act of his whole administration caused more dissension in New Orleans, brought upon the author more criticism, than the establishment of this court. No attention was paid to the fact that Claiborne only very reluctantly retained any judicial functions for himself. It was passionately asserted that justice could not be administered by a man who, like himself, had no knowledge of the two popular tongues — French and Spanish. As a matter of fact, Claiborne had at hand competent interpreters; and to the charge that these men did not always possess a thorough knowledge of the law, it may be answered that most of the cases which came before Claiborne were commercial, that the law on such matters is generally the same in all parts of the world, and that it was perfectly possible for him to decide equably without any special study, from his own general knowledge of the principles involved.

Casa Calvo, down to the date of his departure, early in 1806, worked persistently to estrange the people from the governor. Nor can we blame him altogether for this; since, if he really anticipated an effort by his Government to prevent the permanent acquisition of the Province by the United States, such was his duty, looking towards the possible military exigencies of the case. Every effort was made to discredit the Americans; the fact that Claiborne was constantly surrounded by his own countrymen was exploited to the utmost. It was alleged that he thrust as many of these into office as he could, ignoring the Creole population, though this, as we have seen, outnumbered the foreign element in the proportion of 12 to 1. This was an unjust criticism. Claiborne, if anything, favored the "antient population," as "Laelius" called it. Lewis Kerr, who was a citizen of the Mississippi Territory, was made sheriff on account of his special legal and general qualifications; but the clerk of the new court was Pierre Derbigny. Of four newly-appointed notaries only two were Americans. Offices of honor not involving profit were generally assigned to Creoles. All "civil commandants" but two or three, all of the officers of the militia, a majority of the municipal council, most of the judges of the Court of Pleas, and the larger number of the members of the Board of Health which Claiborne felt obliged to create — these were all "antient" Louisianans. Still another sore spot was the use of English in official business. This, said the critics, menaced "old Louisiana" with political annihilation. English was used exclusively in the custom house; the governor's official letters were written in that language, and it was used in his own court. But in the Court of Pleas French as well as English was officially recognized; in the proceedings of the municipality, French alone was used; and French was the medium in which the correspondence of most of the Louisiana magistrates with the new government was conducted. In reorganizing the militia, Claiborne retained the services of the Americans who had been enlisted by Laussat, but he distributed them through the four companies which he created and gave the command of the battalion to Major Dorci re, a Creole, whose language was French. Still another ground of criticism was the surreptitious immigration into Louisiana of undesirable persons, especially negroes from the French West Indies. Claiborne, as a matter of fact, did all in his power to prevent these unwelcome additions to the population. He ordered that all ships should be inspected at the Balize by the officer in command there; they were next detained at Fort Plaquemines [below New Orleans] till the commandant there was satisfied as to the propriety of permitting the resumption of the voyage; and finally, on arriving at New Orleans, no one was suffered to land until the vessel had been inspected by a committee of the Board of Health. In spite of these precautions, however, there was a steady infiltration of undesirable persons.

It is not to be denied that, on the other hand, something was done to justify the fear and distrust with which the Creoles regarded the new government. A writer in the "Gazette" in November, 1804, while on the whole defending Claiborne refers to the "indiscretion of all parties, their impudent writings and discourses, the contests about country dances. [. . .] An essay written merely to gratify the author's humor has been imputed to the governor of the province as a predetermined insult towards its inhabitants; a private quarrel between two gentlemen, one of them English and one of them French, has almost occasioned a riot." At night insurrectionary placards posted around the streets attracted crowds who resisted efforts to remove the incendiary publications. Duels were frequent; Governor Claiborne's own private secretary and brother-in-law was killed in one, in an attempt to refute a slander. In June and July three public meetings were held, at which prominent citizens joined in preparing a memorial to Congress asking to be speedily admitted to the Union, partly because of the commercial advantages which that would entail, but also because it seemed to offer a route by which the objectionable governor might be eliminated. In one instance the attempt of the sheriff and his posse to arrest a Spanish officer was prevented by the violent opposition of 200 men. Swords were drawn and it was not until a detachment of United States troops appeared that resistance ceased. "This city," wrote Claiborne," requires a strict police; the inhabitants are of various descriptions — many highly respectable and some of them very degenerate." It is a remarkable fact that the amiable and patient governor lived down all these multitudinous causes of complaint; and when he died in 1816 he was surrounded by the respect and affection of his people. The details here set forth have interest as shedding light upon the character of the community, but, most of all, because they explain the origins of that prejudice against Americans and things American, which is the great motive in the history of New Orleans down to the Civil war, a prejudice so deep and all-pervading that the Creole population could come to look on the yellow fever with complacency, nay, almost with affection, since, as Gayarr has said, it attacked the stranger almost exclusively and was, as it were, a weapon against those who threatened the "antient" Louisiana, its language and its supremacy.

Etienne de Bor

First Mayor of New Orleans

Immediately upon taking over the government, Claiborne arranged for the government of the city. He issued a proclamation on December 20th retaining in office provisionally all of the functionaries appointed under the French administration. These included the members of Laussat's Municipality, all except Johns and Sauv, who, being opposed to the new governor on general principles, handed him their resignations. The others, "thus re-elected and confirmed," took their seats anew that afternoon.10 Bor was continued as mayor and the post of "adjoint," or deputy-mayor, made vacant by the resignation of Sauv, was filled by the appointment of Cavalier Petit. Claiborne, in a letter to President Madison, commenting upon these arrangements congratulated himself upon having been able to secure a man of the social prominence of Bor to head the administration. As a matter of fact, Bor was one of the most active leaders of the party opposed to Claiborne. He, Bellechasse and Johns were soon conspicuous in the meetings held by the citizens to protest against the "kind of government which had been forced upon them." They were supported by Daniel Clark, now by the new order of things relieved of his consulate. Claiborne does not seem to have been ruffled in the least by Bor's criticism. On the other hand, Bor's views as to the American Government do not seem to have prevented him from discharging his duties as mayor with assiduity and success.

The members of the municipality renewed their oaths before Claiborne on November 24th. On this occasion the governor made a short address outlining their duties, which were, in effect, to continue the same as under Laussat's administration. The council met for the first time under the new conditions on December 28th and held thereafter sessions once every two weeks. It immediately addressed itself to the matter of the condition of the streets, the regulation of the police force, and the reduction in the number of the "taverns," which was inordinately large. On January 9th we find under consideration regulations for the guidance of persons using the river-front for business purposes. At the next meeting regulations were adopted for the government of public balls. On February 8th the council supplemented its previous action with regard to the bakeries by adopting a whole series of regulations. The bakers were important persons in New Orleans at that time. According to Robin, their business was one of the most profitable in the community. "Many of them make considerable fortunes in a few years," he writes, "and that is not at all astonishing. Kentucky and the other parts of the United States which communicate with the Mississippi send their flour to New Orleans. This flour is of varying quality and consequently at different prices, selling at from $3 to $10 or $12 per barrel of about 190 pounds weight. Sometimes the supply is so great in the city that the price declines below that at the point from which it has been brought. Bakers who are farsighted can lay in a stock at these times, and they make a further profit by mixing flours of inferior grade with the superior." Under the Spanish there was a tax of a picayon per pound on bread. The municipality did not continue the tax, but made rules to regulate the price, thus establishing a precedent which was followed for many years. It now also interfered in regard to other articles of food and passed a resolution fixing the price of beef at one "picayon" a pound, mutton one shilling a pound, and veal and pork eight cents per pound. Other ordinances passed at this time provided for the government of the police, and placing a tax on vehicles. This was all useful and important work. The Council was, however, constantly embarrassed by the fact that it was a temporary organization. It was, moreover, eclipsed by the authority of the governor. His approval was required in practically all cases when important legislation was proposed. It is remarkable, then, that on the whole the municipal government worked with as little friction as it did and still more so, that its achievements were so substantial.

Bor resigned on May 26, 1804, on the ground that his private affairs required his entire attention. He was succeeded by Cavalier Petit as acting mayor. The council saw Bor's retirement with regret and adopted resolutions expressing this feeling and also the hope that the vacancy would be filled by a man equally as able and patriotic. At the same time it endorsed James Pitot as a suitable person for the position. On June 6 Claiborne appointed Pitot to the office. Pitot was descended from a distinguished French family, the founder of which was Ti-Pitot, who commanded a squadron of cavalry in the Seventh Crusade. Antoine Pitot d'Aramon, in order to avoid the religious quarrels then in progress in certain parts of France, removed to Languedoc at the beginning of the sixteenth century and thereafter the family was identified with that province. The father of the new mayor was born in Languedoc in 1695 and died in 1771. He was inspector to the army of the famous Marshal de Saxe, distinguished himself as an engineer and scientist, and became a member of the French Academy. The mayor was born in Rouen in 1761a and was educated at one of the best schools in Paris. At the outbreak of the French Revolution he was taken to Santo Domingo. Thence he moved to Philadelphia and then to Norfolk, Va. In early manhood he settled in New Orleans, where he went into business in partnership with Daniel Clark. Pitot built one of the first cotton presses in New Orleans. It stood at the corner of Toulouse and Burgundy streets. Gayarr speaks of him as "a gentleman of respectability and talent." His career as mayor lasted till July 19, 1805, and was signalized by the incorporation of the city, and the taking of the first steps towards the substitution of an elective magistracy for the appointive one.

Pitot exerted himself to introduce economy into the various branches of the administration, and took an especial interest in the police. In the preceding chapter we have seen that among the first acts of the Laussat Municipality was the enactment of a comprehensive ordinance defining what acts constituted offenses against public order. To enforce this ordinance a small police force was subsequently created, with Pierre Achille Rivery at its head, under the title of "Commissioner General of Police in the City and Suburbs of New Orleans." The wretched pay which the members, officers and men received attracted only the riff-raff of the city into the service. A few ex-Spanish soldiers were enlisted but the council soon found it necessary to authorize the employment of mulattoes to fill the ranks. It was, however, stipulated that the officers should always be white men.

The utter inefficiency of this organization occasioned general complaint and in 1804 it was supplemented by a patrol of citizens, drawn from the militia, and under the command of Colonel Bellechasse. This subsidiary force of volunteers was divided into four squads of fifteen men each, each squad serving eight days, and then being relieved by another. The militia patrol did duty chiefly in the outlying districts. It received no part. In 1805, Pitot made a further reform in the police organization by reconstituting the gendarmerie as a mounted corps, with three officers, three non-commissioned officers and thirty-two men. This was subsequently changed so as to give a force of twenty-two mounted men and ten infantrymen. The mayor was made chief of this corps. In spite of some disputes over matters of authority, particularly as involving the right to appoint the members of this force — a right which the mayor claimed was assigned to him by the city charter — the new system worked fairly well. The militia patrol, which was continued, however, fell steadily in popular favor, partly because of its composition, but chiefly because it made considerable demands upon the leisure of the citizens, and they were not prepared to render indefinitely the services required.

On March 25, 1804, Congress divided the Province of Louisiana into two parts — the upper part being annexed to the Indiana Territory,b and the lower part, which corresponds in boundaries approximately to what is now the State of Louisiana, was erected into the Territory of Orleans. Its government was entrusted to a governor, jointly with a council of thirteen freeholders, to be selected by him; and the judicial powers were to be exercised by a superior court and such inferior courts as this council might establish, the judges of the former, however, to be appointed by the President of the United States. New Orleans was made a port of entry and delivery, and "the town of Bayou St. John" was made a port of entry. On October 1 the new government went into operation. Claiborne was retained as governor. He had been formally inaugurated at the Principal at noon, on October 5. He took the oath before Mayor Pitot, and then delivered an oration in English which was translated into flowery French by Pierre Derbigny. The people were displeased at having the legislative council appointed, instead of elected by them; but the national government, through Claiborne, exercised a wise discretion in the matter of introducing the forms of democratic government, and it was some years yet before the heterogeneous population of New Orleans could be regarded as fit to exercise all the functions of American citizenship. However, a long step forward was made in February, 1805, when the Territorial Council furnished the city with a charter. This charter went into effect early in March. With its adoption the real history of New Orleans, as distinguished from the remainder of the Province or Territory, may be said to begin.

The charter consists of some nineteen sections. It begins by precisely determining the area of the municipality. It was bounded "on the north by Lake Pontchartrain, from the mouth of Chef Menteur to the Bayou Petit Gouyou, which is about three leagues to the west of Fort St. John; on the west by Bayou Petit Gouyou to the place where the upper line of the grant or concession formerly called St. Baine, and now called Mazage passes; from thence along the line of the plantation of Foreel to the River Mississippi and across the same to the canal of Mr. Harang; and along the said canal to the Bayou Bois Piquant; from thence by a line drawn through the middle of the last mentioned Bayou to Lake Cataoucha and across the same to the Bayou Poupard, which falls into the Lake Barataria; on the south by the Lake of Barataria, from the Bayou of Poupard to the Bayou Villars; from thence ascending the Bayou Barataria to the place where it joins the canal of Fazande, and continuing in the direction of the last mentioned canal to the Mississippi, and finally on the east by ascending the Mississippi to the plantation of Rivi re and then along the canal of his present saw mill to the Bayou Depres, which leads to Lake Borgne, and from the point where the last mentioned bayou falls into the said Lake Borgne by a line along the middle of that lake to the mouth of Chef Menteur, and from thence to the Lake Pontchartrain." "All the free white inhabitants" of this extensive tract of land, water, and marsh were declared "to be a body corporate, by the name of the mayor, aldermen and inhabitants of the City of New Orleans."

The officers of this corporation were to be a mayor, a recorder, fourteen aldermen, a treasurer and "as many subordinate officers not herein mentioned for preserving the peace and well-order United States the affairs of the said city, as the city council shall direct." It was made the duty of the governor within ten days after the passage of the act to appoint the mayor and the recorder "out of the inhabitants who shall have resided at least two years therein." The mayor and the recorder were to hold office for at least two years, or until their successors were appointed, and then they were to be appointed annually thereafter. The aldermen, however, were to be elected by the people of the city "on the first Monday of next March." In each ward of the city they were to select by ballot "two discrete inhabitants" to be "aldermen, and represent said ward in the city council." The mayor and the municipality were charged to appoint two inspectors and one clerk in each ward to have charge of this election. The clerk was to record in a book the name of each voter; the inspectors were to receive his ballot and, "without inspecting it, deposit it in a box of which one of them shall keep the key." The election was to last from 9:00 A.M. to 5:00 P.M., and then the inspectors were to count the ballots "in the presence of such voters as care to remain." The returns were to be made by certificate signed by the inspectors and attested by the clerk, to the mayor, who thereupon should publish them and notify the clerk of the city council of the results.

The aldermen thus chosen were to compose the city council. The recorder for the time being was constituted president of this body, but with no vote save in case of a tie; in case of his disability a president pro-tempore might be elected. The aldermen were to take their seats in the City Hall (Principal) on the second Monday in March, 1805, and one-half of the members should serve thereafter till the same date in 1806, and the remainder till the same date in 1807; "so that in every ward there shall be an annual election for one out of the two aldermen." The majority of the council would be deemed a quorum. The council would be judge of the election of its own members. It was empowered to select its own clerk, doorkeeper, and other officers. It was required to meet at least once a month. On the third Monday in March, a "fit and discrete" person was to be elected treasurer thereof, who, under bond of $20,000, with the assistance of two secretaries, was to hold office for one year. The council was invested with the power to make and pass laws and by-laws, and these ordinances, after receiving the signature of the mayor, were to have the force of laws. If the mayor should not approve of these ordinances, he was required to return them within five days, with his objection stated in writing. If two-thirds of the council then present were to vote in favor of the law in spite of the mayor's disapproval, then it was to become a law notwithstanding the veto. If the mayor did not return the law within five days it was to be deemed approved; but under no circumstances could an ordinance of the council have force which contravened any provision of the charter, the laws of the Territory, or those of the United States.

To the mayor and council thus acting together the charter gave the right to tax all real and personal property, with a view to raise funds "to supply any deficiency for lighting, cleaning, paving and watering said city; for supplying the city watch, the levee of the river, the prisons, workhouses, or other public buildings, and for such other purposes as the police and good government of said city may require." But it was provided that no tax for police, lighting, or watering might be put on property not within the parts of the city not laid off into streets. To the mayor and council, moreover, was committed the duty of regulating the price of bread, but not of other provisions, nor could they license drays or carts except in a manner specifically set forth in the charter.

The mayor when elected was to take the oath of office before the governor; the other officers were to taketheirs before the mayor. In case of the disability of the mayor the recorder was to act as mayor pro-tempore, and while so employed the council was to elect a president pro tempore who should preside at its meetings.

The ninth section of the charter dealt with the qualifications of voters, who were to be "free white males residing for one year" in the city, "owning real estate valued at $500 or renting a property of an annual value of $100, or, in case of doubt, to be examined under oath." The tenth section dealt with the duties of the treasurer, and the eleventh with those of the mayor. Among the duties of the mayor were: to appoint "measurers, weighers, gaugers, marshals, constables, scavengers, wharfingers and other officials, as directed by the city council; to license taverns and boarding houses; and to license carriages and coaches for hire." Importance was attached to this licensing matter, inasmuch as it was made an offense subject to a fine not to have the proper license, and one-half of such fines went to "the person who shall sue for same," — presumably, the informant. The mayor was entitled to collect $2.50 for every warrant he might issue, and to any other compensation that the council might decree.

The mayor and the recorder were declared by the charter to be ex-officio justices of the peace. The mayor was to superintend the police and make ordinances for the control of the watchmen and the city guard. He was "to be informed of the intent of every order from the council ordering the disposal of any money or public property." No member of the council could be appointed to any employment or office created by the council. Section XIII transferred to the new corporation any estates previously owned by the Cabildo. The following section provided that all ordinances established by the previously existing municipality were to continue in force insofar as they did not conflict with the present instrument. Section XV divided the city into seven wards. The sixteenth section conferred on mayor and council the right to build sewers, drains, canals, etc., in any part of the city; to open and grade streets; to enjoy certain powers of expropriation of property for these purposes; all expenses incurred for these purposes were to be met out of the city funds. The eighteenth section fixed the recorder's salary at $1,000 per annum. The closing section reserved to the legislature the right to amend and alter the charter at will.

Although brief, this document was fairly comprehensive. The verbiage is often quaint, but its terms are clear and definite. It is remarkable to observe that all of the subsequent city charters reproduce the ideas incorporated in this original instrument. In fact, one cannot but admire its homely wisdom. No less authority than the Supreme Court of Louisiana declared that this charter "like all the statutes passed at the commencement of the American government of Louisiana — to the honor of their authors be it said — is a model of legislative style and exhibits its intendment with a clearness and precision which render it impossible to be misunderstood. [. . .] The whole tenor of the act is a delegation of power for municipal purposes, guarded by limitations, and accompanied by such checks as experience had shown to be wise, expedient, and even necessary for the interests of those who were to be affected by it."

In accordance with the new law, an election for aldermen was called for Monday, March 4. The announcement was made in the columns of the Louisiana Gazette on March 1. Mayor Pitot was deeply impressed with the significance of this first step towards local self-government. In the call he referred earnestly to "the importance of the election," and expressed the hope that the citizens "would consider what degree of zeal and reflection is required in" their "first step towards the enjoyment of 'their' rights." It was also pointed out that "the new council would not be restrained, as may frequently have happened to the municipality, from uncertainty respecting the true extent of their powers and the confidence placed in them by the people." The polling places were established at the residences of Messrs. Lefauchew, Coquet, Romain, M'Laren, Macarty and Bienvenu, and "at the Ball Room." The election duly took place and the following aldermen were chosen: First Ward — Felix Arnaud, James Garrick; Second Ward — Colonel Bellechasse, Guy Dreux; Third Ward — LaBertonni re, Ant. Argotte; Fifth Wardomits the Fourth Ward'? T. L. Harman, P. Lavergne; Sixth Ward — J. B. Macarty, Monsieur Dorville; Seventh Ward — Pore, Guerin.

The installation of the new council was effected with some pomp at the Cabildo (as the Principal was now beginning to be called, ignoring the real significance of that name) on March 11. Claiborne appeared at midday in the council chamber, accompanied by various civil and military authorities, and many citizens. "The members of the municipal corps were found present and measures for the public order having been taken, Monsieur the Governor, proclaimed mayor of the new council James Pitot, who previously had filled the place, and when he had taken the oath in that capacity, the nomination of the governor of Jean Watkins to the post of recorder, or assessor, having been officially read, he took the oath at the hands of the mayor, who then received successively those of Messrs. Felix Arnaud, James Garrick, Joseph Faurie, Fran ois Duplantier, Guy Dreux, Pierre Bertonni re, Antoine Argotte, Thomas Harman, P. Lavergne, J. B. Macarty, F. K. Dorville, Thomas Pore and Fran ois Guerin, chosen by the citizens aldermen or members of the common council." Bellechasse was not present. At the close of this little ceremony Mayor Pitot made a short address in which he gave an account of his past administration, and in particular described what he had done with regard to the police, and the economy which he had introduced into the management of the government. He, Claiborne, and the public generally then withdrew. Watkins took the chair and called the council to order. The secretary, Bourgeois, being absent, Achille Rivery was appointed to act in his place. The only business done was the adoption of a resolution authorizing the mayor to put in force all the ordinances regarding the police already in existence. Thereafter the council regularly met under the presidency of Watkins, until July 27, when Bellechasse having been elected president, he took the place.

Pitot resigned his office in July, 1805. In his message of resignation, he said: "My affairs not allowing me to fulfil the functions of mayor, I have sent to the governor my resignation of that post. Appreciating all the marks of kindness and of confidence which I have received at your hands, I beg you to accept my acknowledgements. Give me your esteem and believe me deeply grateful." That was the ceremonious and graceful way in which things were done in those days. A little later, however, Pitot was able to accept another, though perhaps less onerous post, when Claiborne appointed him Judge of the First Probate Court of the Territory. He remained on the bench till his death, November 4, 1831. When this sad event occurred eulogies upon his life and character were pronounced by the leaders of the local bar, including Pierre Soul, Mazureau, and Bernard Marigny. Chief Justice Bermudez, speaking of Pitot's services as a judge, has said that "in the early days and more advanced life of this State, with Judge Martin and his associates, all of imperishable memory and luster, he proved of unappreciable assistance in expounding the new laws which followed the anterior legislation in giving good judicial proceedings a proper form and shape for the administration of justice, and in laying down a solid basis for the statutory jurisprudence with which the state is blessed."

The Author’s Notes

Figure.

Waring and Cable, Social Statistics of Cities, Report on New Orleans, 29-32.

Profession. Robin, Voyage dans l'intrieur de la Louisiane, II, 75 ff., quoted in Phelps, Louisiana, 207-214.

Times. Martin, History of Louisiana, Howe's edition, 295.

Citizen. Gayarr, History of Louisiana, IV, 1-3.

Powers."Laelius," in the Louisiana Gazette, November 9, 1804. This article was evidently written with the full knowledge and approval of Claiborne, of whose acts it is a convincing defense.

Territory. Martin, Louisiana, 294. Casa Irujo subsequently withdrew for his master all opposition to the cession, and denied that there had ever been any intention of resisting it.

Justices. Gayarr, History of Louisiana, IV, 3; Martin, Louisiana, 319; Dart, Sources of the Civil Law of Louisiana, 37-40.

Riot.Louisiana Gazette, November 9, 1804. See also the "Esquisse de la Louisiane," printed anonymously in 1804, referred to in Robertson, "Louisiana under the French and the American Regimes," II, 269.

Supremacy. Gayarr, Louisiana, IV, 636.

Disappeared.The official record of the installation of the municipality as preserved in the City Archives of New Orleans reads; "Proces-verbal of the Reinstallation of the Municipal Corps the Day of taking possession of the colony by the United States."Today, December 20, 1803, of the Christian era, the commissioners or agents of the United States, W. C. C. Claiborne and James Wilkinson, being present at the Hotel de Ville, in the meeting room of the municipality, with the citizen Pierre Clement Laussat, Colonial Prefect of the French government, in order to receive from him possession of the colony or Province of Louisiana, and this important act having been effected, His Excellency, W. C. C. Claiborne, named by the President of the United States Governor General and Intendant of said Province, has had read his proclamation, by which he orders maintained provisionally in their functions all of the public officers who existed under the French government, and also all municipal enactments issued to date; consequently Messrs. the Mayor and the members of the Municipal Council (except Johns and Sauv, who have resigned), thus re-elected and confirmed, have taken their seats anew, and the meeting has adjourned to Thursday, the 24th of the current month; in faith whereof the present proces-verbal has been signed by the recording secretary. "Signed: Bor, Tureaud, Faurie, Donaldson, Destrehan, Fortier, Livaudais; Derbigny, Secretary."

Superior. Quoted in Phelps, Louisiana, 211.

Corps.Resolution of May 6, 1805.

Required. See Rightor, Standard History of New Orleans, 110, 111.

United States. Phelps, Louisiana, 222, 223; Martin, Louisiana, 320, 321.

Section. Louisiana Gazette, February 22, 1805. This act was approved by Claiborne February 17, 1805.

Act. Louisiana State Bank vs. Orleans Navigation Co., 3rd annual repts., 305.

Pore,Guerin. Louisiana Gazette, March 5, 1805.

Council. Records of the City Council, in the New Orleans City Archives, Session of March 11, 1804.

Days. See the letters of the mayors in the City Archives of New Orleans, July 19, 1805.

Bernard Marigny. Pitot's son, Armand Pitot, born in New Orleans in 1803 and died in 1885, had a scarcely less distinguished career than his father. He was educated in France, and on returning to New Orleans was named Clerk of the Supreme Court, was admitted to the bar, named translator to the House of Representatives, and became a member of the City Council (1838) and, finally, was made secretary of the commission appointed to revise the Civil Code of Louisiana. For thirty years and more he was the legal advisor of some of the most prominent banks in the city, notably the Citizens' Bank.

Blessed. See King, "Old Families of New Orleans," Chap. XXXV.

Chapter V

The First Two Mayors

The appointment of John Watkins to be mayor, vice Pitot, resigned, was announced on June 27, 1805. In selecting Watkins for the vacancy, Claiborne was governed by the fact that he had served acceptably as recorder and was in line for promotion. He was a physician by profession and had previously been a member of the territorial council. The two years over which Watkins' administration extended were interesting and important. They witnessed, among other things, the incorporation of the College of Orleans, the visit of Aaron Burr, and the establishment of the first Protestant Church in New Orleans. He came into office at a time when people were disposed to complain of the small benefit resulting from the creation of the city government. He had to sustain a good deal of adverse criticism. Two matters of importance urged before the council were, the improvement of the market and the extension of the streets. The existing market had been erected by the Spanish Government in 1791. What was now needed was an extension to accommodate the vegetable venders. The finances of the city were not just then in a condition to permit this work to be done. Not until 1822 was it possible to meet this demand. The growth of the "fauxbourgs" was so rapid that the need for extensions of the streets of the "Vieux Carré" out into the new regions was obvious, but for some reason the council refused to accede to this reasonable demand, and even declined to order the removal of Davis' rope-walk, which blocked the egress from the "Old Square" for a considerable distance along Canal Street. We may suspect that in this opposition to the extension of the streets the prejudice of the Creole against the American figured to no inappreciable extent.

Watkins was more successful in regard to the police. There was a strong prejudice against the "gens d'armes," as they were called. These were composed to a considerable extent of soldiers who had served under the Spanish. A writer in the Louisiana Gazette referred to them as a "nuisance," and said that the corps was "unlawful and unnecessary." In deference to public opinion the council in 1806, created a city police force, known as the "garde de ville." This organization was intended to be a purely civic police. The military element was eliminated. It consisted of one chief, two sub-chiefs or assistants, and twenty men for the city proper; two sub-chiefs and eight men for the Faubourg Ste. Marie, now called the First Municipal District; a total of thirty-three men. The chief was provided with a horse and allowed a salary of $60 per month, from which he was supposed to provide feed for his mount. The sub-chiefs received $20 each, and the watchmen $20 each. The men were armed with the old-fashioned half-pike, and carried a saber suspended from a cross-belt of black leather adorned with a large brass-buckle, on which the words, "Garde de Ville" were conspicuously engraved. The headquarters were at the City Hall (Cabildo). Here two men and one sub-chief were always on duty as a sort of relief force or reserve. The guard was changed in summer at 7:00 A.M. and in winter at 9:00 A.M. This new force went on duty on March 14, 1806. It did not last long. Two years later it was suppressed by the city council as incompetent. There was good ground for this action. Within two months after its organization, it undertook to suppress a riotous demonstration in the city, but not only was unsuccessful, but the mob set upon the watch, deprived it of its weapons, and beat the men badly. For this exhibition of cowardice the council formally deprived the watch of its arms. The grand jury joined in the popular demonstration against the police for its failure to enforce order, and rendered a report in which it declared that "the city was at the mercy of brigands to loot and pillage at pleasure." The case specifically referred to by the grand jury was the murder of a man in the Faubourg Ste. Marie by footpads. The body was left lying in the streets three days, untended by the police, until at last some charitable persons removed and gave it burial.

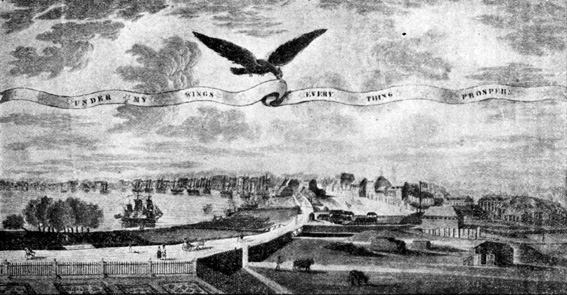

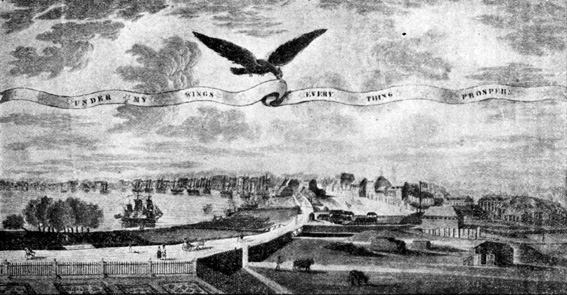

New Orleans in 1803a

Under Watkins' initiative the council also undertook to deal with the problem of fire prevention. This was a problem always urgent in the early history of the city. Although there was at this time a growing disposition to build solidly of brick, and consequently, there has been no repetition of the great conflagrations of 1788 and 1794 — the majority of the dwellings in the city were of inflammable construction and there was consequently constant peril of serious fires. In 1806 the council passed a number of wise regulations, one of which prohibited the use of shingle roofs, and another provided for the inspection of chimneys, and others still established rules for the police in case of fire to prevent looting and other depredations, of which there was much complaint at this time.

The territorial council passed the act creating the College of Orleans in April, 1805, and in July an organization was effected to put in operation, Ex-Mayor Pitot being chosen vice chancellor. The college was the first institution of learning projected in the Territory of Orleans. It was the outcome of an attempt on the part of the government to create a complete educational system, which would include preparatory schools and public libraries in all parts of the territory subject to its jurisdiction, but which would have the university as its head and crown. The territorial council made various ill-judged plans to finance the institution, including a lottery scheme, but at Claiborne's wise motion, finally determined to impose a tax for the purpose. The city contributed a site and buildings, which were located at the corner of Hospital and St. Claude streets, on the site now occupied by St. Augustine's Church. In spite of further assistance from private parties, the institution was not ready to open its doors till 1811. In the meantime the matter of public education was much neglected. Rev. Philander Chase, who was called by the Protestants of the city to take charge of the congregation of Christ Church, opened a school on his arrival in the city in 1806, which soon had a good attendance, and thrived until his departure in 1811. The Ursuline nuns conducted a successful school for girls, but otherwise there seems to have been no provision for the important matter of the instruction of youth.

New Orleans has always been a predominantly Catholic city, but with the establishment of the American government in Louisiana, there was gradually formed in the city a group of Protestants sufficiently large to make the need felt of a church in which they might worship. As early as 1803 there is record of a Rev. Lorenzo Dow who ministered to the scattered Protestants in the Attakapas. In 1805 the Rev. Elisha Bowman, who was regularly stationed in Opelousas, is said to have occasionally conducted services in New Orleans. In 1805 the Louisiana Gazette printed an appeal to the English speaking population of New Orleans to "show that it was not irreligious." Resolutions to establish a Protestant church in the city were adopted at a meeting held on May 29 at Francisque's ball-room. A second meeting was held on June 2 at the residence of Mme. Forager, on Bourbon Street, between Customhouse and Bienville streets. At another meeting on June 11 it was decided to call a Protestant clergyman to take charge of the proposed congregation, and the sum of $2,000 per annum was guaranteed by subscriptions from those present to pay his salary. On June 16 a vote was taken to see with what denomination the congregation should affiliate, with the following result: Episcopalians, 43; Presbyterians, 7;Methodist, 1. The act incorporating the congregation under the name of Christ Church, received the approval of Governor Claiborne on July 3, 1805. Under this act Protestant services were held, for the first time in the history of New Orleans (except, perhaps, for such occasional ministrations as the Rev. Mr. Bowman had supplied) on Sunday, July 15, 1805, at the residence of a Mr. Freeman. Doctor Chase, who was called to the rectorate, arrived in the city from New York, October 20, 1805. He held his first service at the City Hall (Cabildo) on November 17, 1805. Thereafter Protestant forms of worship were observed regularly every Sunday, though the congregation had no permanent domicile until nearly twenty years later, meeting sometimes at the Cabildo, sometimes at the courthouse, and more often at private residences.

The period of Watkins' administration was one of no small anxiety for Claiborne and the territorial government. The ownership of West Florida was arousing much ill feeling between the Spanish and the Americans, particularly among the hardy adventurers in the West whose insistence had influenced so largely the acquisition of the Province of Louisiana by the United States. Jefferson's desire to settle all such difficulties by diplomacy rather than by force did not appeal to the Kentuckians and Tennesseans, and there was a strong tendency to filibustering throughout the Mississippi Valley. Of this restive spirit both General James Wilkinson and Aaron Burr were eager to take advantage. Burr was then vice president of the United States, but on account of his duel with Hamilton, in which the latter had been killed, he was in ill repute in the North and East, and sought elsewhere fields of activity in which his distressing antecedents would not be remembered, or, at least, would not be held against him.

On the afternoon of July 25, 1805, in "an elegant Barge," with "sails, colors and oars," manned by "a sergeant and ten able, faithful hands," the ostracized vice president arrived in New Orleans. He was fresh from a visit to Wilkinson at Fort Massac, and brought with him now letters from that officer to Governor Claiborne, General John Adair and Daniel Clark. In his epistles to Adair and Clark, Wilkinson hinted darkly at some magnificent design which Burr entertained, and which he would unfold to them. To Adair he wrote: "He understands your merits and reckons on you. Prepare to visit me and I will tell you all. We must take a peep into the unknown world beyond me." He told Clark that "this great and honorable man would communicate to him many things improper to put in writing, and which he would not say to any other." It is supposed that Burr had ideas of separating the western part of the United States from the remainder and setting up there an independent government of some sort with himself at his head; failing which, he dreamed of an attempt against the Spanish in Mexico, with New Orleans as a basis of operations. There was at that time in New Orleans a strong sentiment in favor of independence for Mexico. A society, in which Mayor Watkins was a leading spirit, existed to promote this idea. Burr met Watkins, and through the latter's influence secured the endorsement of this organization. The visitor remained ten or twelve days in the city, during which time he received much social attention. Claiborne, who was not informed of his vague schemes of personal aggrandizement, entertained him at a banquet. Then he departed in the "elegant barge," for St. Louis, leaving behind no definite idea of what he proposed to do, save an impression that he meditated a great filibustering expedition against the Spaniards somewhere, sometime, somehow.

It is not necessary here to follow Burr's subsequent career; suffice it to say that the rumors of his shadowy enterprise were kept afloat in the country a twelvemonth, and served to agitate the public mind everywhere, but especially in New Orleans. Claiborne, partly on the basis of these reports, but also from what he knew of the state of partial mobilization in which the Spanish forces were kept on the frontiers of his territory, anticipated war between the United States and Spain at no distant date, and made what preparations he could for that event. He was surprised, therefore, when in the winter of 1805-6 Wilkinson removed from New Orleans a large part of the little garrison and sent it up into the Mississippi Territory. To supply the gap in his ranks he appealed to the loyalty of the Creoles, and at first met with a gratifying response. Later on, as the first flush of enthusiasm evaporated, he was compelled to find excuses for their delinquencies: "Society," he wrote, regretfully in January, "is now generally engaged in what seems to be a primary object, the acquisition of wealth," to the exclusion of all other objects.

Two incidents which tended to convince Claiborne that he had reason to fear Spanish designs on New Orleans now occurred. The first was the affair of P re Antoine de Sedella, the Spanish monk, who, as we have seen, tried to introduce the Inquisition in the times of Miro, and who, as we shall see later on, having been purged of many faults, ended by dying reverenced as a saint by the entire community. Sedella was apparently wholly under the influence of Casa Calvo, Morales, and the rest of the Spanish clique which for several years after the acquisition of the Province by the United States made its headquarters in New Orleans, and labored to create difficulties for the new government. "We have here a Spanish priest who is a very dangerous man," wrote Claiborne, in one of his letters to the Secretary of War in Washington; "he rebelled against the superiors of his church, and, I am persuaded, would even rebel against this government, whenever a fit occasion may serve." He accused him of "embracing every opportunity to render" the negro population "discontented with the American government." Sedella fell out with the vicar general, Walsh, with the result that in June, 1803, he was deprived of his "faculties," and forbidden to exercise any priestly offices. This action occasioned great turmoil in New Orleans. The people supported him almost to a man, and, as Miss King says, in her delightful account of this famous controversy, "elected" him parish priest in the face of the opposition of his clerical >superior. Watkins supported Sedella, and when he learned that Walsh was meditating the publication of a pamphlet in which the whole matter was to be set forth, interposed to prevent its >publication, on the ground that such a work would tend to cause a violation of the public peace. Walsh took the quarrel up to Claiborne. He alleged "the interruption of the public tranquility," in justifying his request for the support of the civil arm, "which has resulted from the ambition of a refractory monk supported in his apostacy by a misguided populace, and by the constitution of an individual (Casa Calvo?) whose interference is fairly to be attributed less to zeal for the religion he would be thought to serve, than to the indulgence of private passion and the promotion of views which are equally dangerous to religious and civil order." But Claiborne declined to interfere unless there were some actual violation of the peace, and advised "harmony and tolerance." Later on, in October, Claiborne, feeling that Sedella's influence was being used to undermine the position of the Americans in New Orleans, and to prepare the way for a Spanish descent upon the city, summoned the priest to the government house, and, in spite of his protestations of loyalty, required him to take the oath of allegiance, in the presence of Mayor Watkins and of Colonel Bellechasse.

The other incident was connected with Casa Calvo, himself. This wily intriguer went, in October, 1805, on a journey into the western part of the territory. There was this much occasion for his perturbation about New Orleans and the Spanish — in the bank of the little city lay a sum of money reckoned very large in those days — not less than $2,000,000. The bank had been organized in 1804 under the name of the Louisiana State Bank, and opened for business in January, 1805; but in addition, there was a branch of the United States Bank, of Philadelphia, which likewise had on hand a large amount of specie. Claiborne seems to have felt that one phase of the Spanish plot, which he suspected but could not precisely put his finger on, was to loot these institutions. He sent an American military officer to accompany Casa Calvo to Natchitoches, and report his actions; and they were sufficiently suspicious to convince the young governor that immediate action was necessary. On the return of the Spanish nobleman he received a courteous letter suggesting that he and Morales ought now to bring to an end their unnecessarily prolonged stay in Louisiana. They ignored the hint, and in February, 1806, Claiborne sent them their passports, politely wishing them a pleasant voyage to whatever part of the Spanish king's dominions they might wish to proceed. Casa Calvo was naturally very indignant at this procedure, but had no option save to depart. The incident had, of course, the effect of increasing the tension between the United States and Spain, and the young American governor was more than ever certain that he had now to look to hostilities between the nations.

Into this strained situation there was now injected another and troublesome element. When Burr left New Orleans, in July, 1805, it was with the understanding that he would return in the autumn. He never returned but he sent to the city certain emissaries, whose duty it was to keep alive the sentiment in his favor there. The most prominent of these were Samuel Swartwout, Dr. Eric Bollman and Peter V. Ogden. In October Swartwout, with a confidential letter from Burr, went to Natchitoches where Wilkinson had established his headquarters. He was received with much attention, remained eight days, and then returned to New Orleans. What happened after that is not clear. Wilkinson adopted a procedure which cannot well be explained, but which, at any rate was productive of the most singular consequences for New Orleans. He dispatched a letter to the President of the United States, exposing Burr's nefarious schemes, so far as he knew of them. Then he sent Major Porter to New Orleans with a force of artificers and a company of a hundred regulars, and a few days later he himself hastened down to the city. They arrived in New Orleans early in November. Then followed the hurried repairing, remounting and equipping of every piece of artillery in the town, the preparation of munitions of all descriptions, the overhauling of harnesses and the manning of the forts, the issue of contracts for palisades and instruments of defense, and other evidences of preparations for what was supposed to be an expected attack; and the city was plunged into a state of panic.

In the meantime Burr was on his way down the Mississippi with a force of men which rumor multiplied into a formidable little army, but which was actually a mere handful. Wilkinson had ordered it stopped at Natchez. Was he apprehensive that the arch-conspirator would elude his representatives at that point, and make his way down to the city? Or was he fearful that Clark, Watkins, and other known confidants of Burr in New Orleans would, on hearing of his approach, raise the city in his favor? At any rate, he contrived to create in the minds of the loyal citizens the impression that a grave military necessity existed. He demanded that Claiborne declare martial law. The discrete governor refused to take this extreme step, but consented to a meeting of the Chamber of Commerce, and called out the militia, one company of which remained under arms thereafter until the disturbances were at an end. Wilkinson furnished vague but lurid information to the Chamber of Commerce; a large sum of money was subscribed for purposes of defense, and a temporary embargo was recommended on the port for the purpose of facilitating the enrollment of sailors, whom Wilkinson declared he needed. Claiborne mistrusted Wilkinson's motives. He had been advised by Cowles Mead, acting governor of the Mississippi Territory, that Wilkinson was a "traitor [. . .] little better than Cataline." Wilkinson, on the other hand, declared that he "had been betrayed, and therefore 'would' abandon the idea of temporising or concealment the moment after I have secured two persons now in this city." These persons were Burr's confidential agents. On December 14th he arrested Bollman. Two days later Swartwout and Ogden were apprehended at Fort Adams and brought down to New Orleans on a bomb-ketch, which anchored in front of the city. A writ of habeas corpus was sued out, but the people, who evidently approved heartily of Wilkinson's measures, offered a passive resistance to its execution which was entirely effective; the court official who undertook to serve the writ found that he could not hire a boat to take him out to the ketch, and the following day, when he did succeed in getting a skiff, he reached the vessel only to find that Swartwout had in the meanwhile been spirited away. Ogden, however, was set free, but Wilkinson immediately had him re-arrested along with a man named Alexander, and held them both in defiance of writs of habeas corpus issued by judge Workman, an attachment against himself, and an appeal to the governor to sustain the authority of the court with force. Workman resigned by way of protest. Wilkinson was in supreme control of the city.

On January 14, 1807, General Adair arrived in New Orleans with the intelligence that Burr would reach the city within the next three days, but without an army — with, in fact, only a single attendant. One would think that discouraging piece of news would have disposed of any possibility of danger, if any ever threatened, of an uprising in New Orleans, as it did of any possibility of an attack on the city at Burr's hands. Burr, as a matter of fact, never passed Natchez. Wilkinson, however, for some reason, felt it necessary to take Adair into custody. A force of 120 regular soldiers surrounded the hotel at which he was staying, and he was arrested while seated at the dinner table, thrust into confinement, and a few days later removed from the city. That day the troops were all under arms; patrols marched up and down the streets of the terrified city, and every person of whom the commander seems to have felt any suspicion was put under arrest, including Judge Workman. At this inopportune moment a Spanish force of 400 men from Pensacola arrived at the mouth of Bayou St. John and sent a messenger in to the governor to request permission to cross American territory to the post at Baton Rouge. Needless to say, this privilege was refused. The circumstances seemed to justify Wilkinson's wildest apprehensions.

Suddenly the whole strange business came to an end. The community awoke from the bad dream which obsessed it. The Legislative Council on January 22d addressed to the governor a communication in which it disclaimed on behalf of the Creoles any sympathy with or participation in the treasonable designs of Burr. Then the members announced their intention to investigate Wilkinson's "extraordinary measures [. . .] and the motives which had induced them, and to present the same to the Congress of the United States." There is, however, some indication that Wilkinson was acting with Jefferson's approval.

On January 28th the news of Burr's arrest at Natchez was received in New Orleans, and on the 3d of March, that he had been re-arrested at Fort Stoddard, Alabama. About the middle of May, Wilkinson sailed from New Orleans for Virginia, to testify in the trial of Burr. With his departure the last trace of disorder disappered.

In the midst of this exciting episode Mayor Watkins was called on to deal with another danger much more real and terrible in character. This was a conspiracy among the negro slaves to burn the city and slaughter the inhabitants. "It seems that a white man, a fresh importation from Santo Domingo, where he had doubtless served an apprenticeship to the crimes which have plunged that unfortunate island into the depths of destruction, has been for some time employed as a workman in the shops of Mr. Duverne, a respectable citizen of the Faubourg Ste. Marie," wrote Watkins, in a long communication to the council, describing the occurrence, under date of September 28, 1805. "One day this wretch, who was named Grandjean, confided to a fellow employee, a mulatto man named Celestin, who was likewise employed by Duverne, a plan for a general insurrection of the slaves, the success of which would involve the destruction of the lives and fortunes of the whites." "Celestin," continued Watkins, "guided by natural sentiments of humanity, like a faithful slave, and without loss of time, communicated the information to Mr. Duverne, who, in turn, and conjointly with Celestin, apprised me thereof, accompanied for that purpose by Colonel Dorci re. Measures were immediately taken not only to frustrate the plot and apprehend its author, but to secure sufficient proof to convict him of the appalling crime which he was concerting against the peace of the territory. With this object in view we advised several free persons of color, both intelligent and of good character, to get themselves presented to Grandjean as individuals likely to second him in his enterprise, and who, under this disguise, were to obtain from him all the details of the conspiracy, in order to fit themselves to give testimony eventually before the courts. This plan proved successful, for Grandjean committed himself fully to them and explained his scheme, which was to be carried out in the following manner: He said that, although the real leader, he was to be known only to ten persons, who were to be the ostensible chieftains. These ten chiefs were then to communicate the secret to ten others, and so on indefinitely. Messengers were to be sent among the negroes at Natchez and to those at adjacent places. 'Commandeurs' or negro 'drivers' were to be especially won over, and at an appointed hour on a certain day the decisive blow was to be struck. The insurgents were to make themselves masters of the different streets of the city, get possession of the soldiers' barracks, and of the different public warehouses, surprise the state house, and other government buildings, massacre everyone who offered resistance, and finally set the city on fire, if it could not be subjugated in any other way."

As soon as the mayor had in hand all the threads of the conspiracy he called in consultation Colonel Bellechasse, Col. Dorci re and Mr. Duverne. A force of gendarmes was taken along. They surrounded the Duverne workshop. Bellechasse found a position where, without being himself seen, he was able to overhear Grandjean talking to his fellow operatives and obtained in this way a confirmation of the information that had already been laid before the mayor. The place was then raided and Grandjean was put under arrest. He was put in prison, brought to trial and received a life sentence at hard labor in the chain gang.

The mayor brought before the City Council the matter of an award for Celestin and the other colored people who had by their loyalty averted what could hardly have failed to prove a serious situation, even had the projected uprising failed of the terrible completeness which its originator hoped for it. The Council deputed two of its members, Messrs. Pedesclaux and Arnaud, to confer with Celestin's master, a Mr. Robelot, with reference to his manumission; and the price of $2,000 having been agreed upon, the corporation appropriated the money, and the mulatto became a "free man of color." The Council also adopted resolutions eulogizing the other negroes who had assisted in trapping Grandjean and made substantial grants of money in their favor.