Benjamnin F. Butler.

Butler’s Book: Autobiography and Personal Reminiscences

of Major-General Benjamin Butler.

Publishers’ Preface

Dedicatory

Preface

CHAPTER VI.

“CONTRABAND OF WAR” BIG BETHEL AND HATTERAS.

Captured Negroes declared to be “Contraband of War” — Story of the Origin of the Phrase — Possibly not good Law, but a Handy Expedient — Sensation Created — Some remarks concerning Mr. John Hay as a Historian — Difficulty in obtaining horses — Decides to dislodge Confederate Forces at Bethel — Order for detail of the Movement — Gross mismanagement of Plans — Union Troops fire upon each other — In Front of the Breastworks — Orders disobeyed and attack given up — Enemy’s condition investigated — Battle of Bull Run — General Wool sent to Fortress Monroe — Attack on the Forts at Hatteras — Their Surrender — Midnight Ride to Washington — Telling welcome news to the President — A Waltz en Dishabille — Goes home to Lowell — The Battle of Bull Run critically considered . . . 256

CHAPTER VII.

RECRUITING IN NEW ENGLAND.

Finds Recruiting at a standstill in New England — Reason: only Republicans made Officers — Interview with the President on the subject — Obtains authorization to raise troops — How Democratic-Colonels were obtained — A Connecticut regiment, Colonel Deming — A Vermont regiment, Colonel Thomas — A New Hampshire regiment, Colonel George, almost — Ex-President Pierce Plows with the Heifer — Lincoln’s Bon Mot — A Maine regiment. Colonel Shepley — A Massachusetts regiment. Colonel Jones — Establishes Camp Chase at Lowell — Governor Andrew flatly refuses to appoint Jonas French Colonel or Caleb Cusliing Brigadier — Trouble — Hastern and Western Bay State regiment recruited — “Connecticut over the Fince” — How riotous soldiery were disciplined — Seizure of Mason and Slidell — We should have fought England, and could have beaten Her — Interview with Lincoln — Believes in moving on the Enemy in Virginia — The President drops a hint — McClellan gets a “Yankee Elephant” out of the Way . . .294

CHAPTER VIII.

FROM HATTERAS TO NEW ORLEANS.

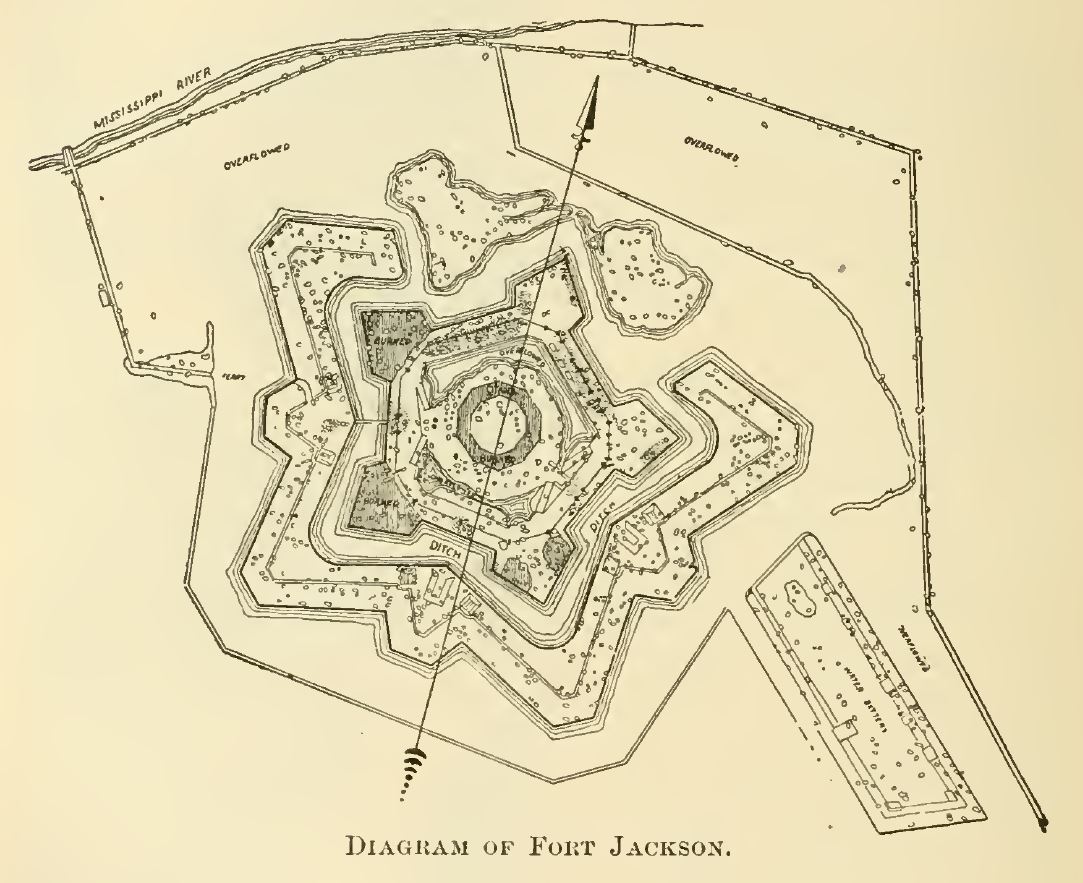

Sailing to the South — Ashore on the Shoals of Hatteras — A Narrow Escape — A Maine Chaplain’s Cowardice — Yankee Ingenuity stops a leak — Arrival at Ship Island — Making ready for the Attack on New Orleans — Hampered but not delayed — Below Forts Jackson and St. Philip — Porter’s Mortar-Boat Fiasco — Cutting the Chain Cable — How Farragut passed the Forts — Army goes down the River and up the Coast and moves against the Forts from the Rear — Circumstances of their Surrender to Porter — Testimony of the Confederates — Some remarks concerning Porter . . . 337

CHAPTER IX.

TAKING COMMAND OF A SOUTHERN CITY.

Entering New Orleans — The City untamed — Meeting the City authorities at the St. Charles Hotel — Howling mob surrounds the building — “Tell General Williams to clear the streets with Artillery” — Proclamation to the Citizens — Buying sugar to ballast vessels — Property burned at instigation of Confederate leaders — Alone responsible for conduct at New Orleans — Utterly destitute condition of people — Providing Provisions and Employment — Approach of Yellow Fever Season — Alarm of Troops — Disease investigated, with Theory as to Cause — How the City was cleaned and Kept clean — Just two cases of Fever that Summer — Further consideration of Yellow Fever subject — How It was fought at Norfolk and New Berne two years later — One thing West Point needs . . . 373

CHAPTER X.

THE WOMAN ORDER, MUMFORD’S EXECUTION, ETC.

Conduct of Women of New Orleans toward Northern Soldiers described — Some Examples — Butler’s personal Experience — Spitting in Officers’ Faces — “I’ll put a Stop to This” — General Order No. 28 comes out — It does put a Stop to it — How it affected the Wife-Whippers of England — “Honi Soit Qui Mal y Pense” — Reward offered for Butler’s Head — The Other Side: The Noble Women of New Orleans — Trouble with “Neutrals” and Whipper-Snapper Consuls — Assessing wealthy Confederates to support the Poor — Mumford tears down the Stars and Stripes — Is Arrested and Sentenced to Death — Butler threatened with Assassination — The Wife’s appeal — Mumford hanged — Eight Years later — Depredation harshly punished — Butler’s wonderful Spy system — A Spy in every Family — Negro servants tell all — Some amusing Instances — “I want that Confederate flag, Madam, for a Fourth of July Celebration in Lowell” . . 414

CHAPTER XI.

MILITARY OPERATIONS.

What was Ordered — Mobile of no Consequence — Baton Rouge seized — Farragut and Williams advance upon Vicksburg — Halleck asked for aid — He refuses — Some Strictures on his conduct — Digging the Canal at Vicksburg; — Fall in the River — French Vessel before New Orleans — An International Episode: France to recognize the Confederacy, liberate New Orleans, be given Texas and capture Mexico — Butler meets the Emergency — The Forts strengthened — Justification found for firing on a French Flat — The Loyal and Disloyal Citizens put on Record — All Arms ordered Given Up — Porter’s Bombardment of Vicksburg — Battle of Baton Rouge — Admiral Porter’s Brother — “Lying is a Family Vice” — General Phelps’ resignation — General Strong at Pontchatoula — Louis Napoleon again — Admiral Reynaud at New Orleans — Negro Regiments organized — Weitzel’s Expedition — His objection to Negro Soldiers answered — Twelfth Maine at Manchac Pass . . . 454

CHAPTER XII.

ADMINISTRATION OF FINANCES, POLITICS, AND JUSTICE. — RECALL.

Becomes his own “Secretary of the Treasury” — Debased condition of the Currency — Compelling the Banks to pay out Specie — Curbstone dealers in Confederate money — Their Course a reliable news Barometer — Street Disturbances — Case of Mrs. Larue — No money to pay the troops — Farragut’s Appeal for influence — Adams Express Company called on — An Army self-supported — Banks’ subsequent Troubles — “General Butler didn’t give Reasons for his Orders” — The Confiscation Acts enforced among the Planters — Congressional Election — Count Mejan, the French Consul — Major Bell administers Justice — Intimations of Recall — Napoleon’s demand and Seward&rsquop;s compliance — General Banks arrives — Butler in Washington, seeking Reasons — Interviews with Lincoln, Stanton and Seward — Double-dealing of the latter shown — Farewell Address — Davis proclaims Butler a felon and an outlaw — $10,000 Reward — Lincoln desires Butler’s services — Return to Lowell . . . 604

General Butler has said in his introduction that every point is to be proven. This has necessitated a large staff of workers to carefully search the records of the War Department, and the consequent proof corrections have occasioned a long delay in the publication of the work, and required the reprinting of many folios. The work has in consequence been increased in number of pages and illustrations not originally announced or contemplated, making, we trust, valuable and interesting additions.

The historical documents have been placed in an appendix with references at the bottom of each page, thus elucidating and proving all statements, and adding accordingly to the value of the work as an authentic autobiographical history. The object of placing these documents in an appendix was to retain the logical sequence of historical events and not to break the thread of the story. Among the vast amount of data it is very possible that some errata may appear in the first edition, but mistakes will be duly rectified in the subsequent editions.

An impression prevails that by waiting a short time after the publication of a popular book sold by subscription, it may be bought at reduced prices at bookstores, dry-goods stores, news stands or as premiums for periodicals. This impression owes its inception to the practice of some publishers, who, for reasons — probably of a financial nature — have found it to their advantage to reduce the price of subscription books, after the first popular sale is over, and place them in bookstores, expose them in public libraries, and even permit them to be advertised and given as cheap premiums for periodicals, newspapers, etc. Besides this, of late years there has been a constant effort by bookstores and dry-goods stores to sell standard subscription books below cost as an advertisement.

It is not surprising that the public sometimes looks with distrust upon the promises of subscription book publishers, or their agents, who, having pledged themselves that the original price shall be maintained, have in many cases deliberately broken faith.

In consequence we feel it incumbent upon us to offer the public something of more value than promises, which are the poorest possible collateral.

The following guarantee will, we trust, convince subscribers of our sincerity, and we feel confident that the plans we shall adopt will enable us to enforce it.

Butler’s Book is published as a subscription book and to be sold by us only as such through our agents, and at prices appearing in our prospectus or on our circulars.

Should we at any time offer or advertise this work for sale in book-stores, dry-goods stores, etc., at reduced price, or sell it to be sold, or given away as premiums for magazines, newspapers, etc., we agree to refund to each subscriber the difference between the regular retail price and such reduced price.

This guarantee, which appears in every copy, is, we believe, the first guarantee of a tangible, monetary value ever given to subscribers of subscription books, that the promises made by publishers or their agents are to be carried out.

To protect our subscribers and agents, we consulted the most eminent legal talent, and in answer received the following letter from General Butler, which will doubtless be received with more than ordinary interest, containing as it does the opinion of a lawyer second to none in the world: —

Boston, Oct. 5, 1891.

A. M. Thayer & Co., 6 Mt. Vernon St., Boston, Mass.

Gentlemen: — I have taken note of the performances now going on by publishers of important books, who, after they have made solemn engagements that their books shall be sold only by subscription, and put enormous prices on them upon that pledge, by which assurance the reading public have made purchases to the amount of some millions of dollars, have turned around, and, advertising that the exact copyright work will be given to anybody who will subscribe for a magazine or newspaper, as a chromo as it might be termed, has heretofore been used. Now, I don’t want my book used as a chromo, and I know you would not do it, and you have sent a guaranty to me that it shall not be done, and that, as far as I am concerned, is quite sufficient. I think you may well do so, because it is my belief as a lawyer that these publishers are liable to their subscribers for the difference between the chromo price and the subscription price of these works, and if I had not gone out of the law business, I should like to undertake the present job of collecting it in behalf of these subscribers to these several works.

Therefore, I will stand by you and aid you in every way to prevent any such occurrence as is now going on, to the utter destruction, I should suppose, of the business of selling valuable books by subscription, a method which is of great value to the public.

Truly yours,

(Signed) BENJ. F. BUTLER.

All agents for Butler’s Book enter into an agreement : —

“Not to sell or deliver directly or indirectly, a copy of this work to anyone who does not actually subscribe for it for his own private use, and not for resale, and not knowingly to supply a copy, directly or indirectly, to any bookstore, bookdealer, news agent, or public library, nor be accessory to the same being done in any manner, and not to sell or to supply copies to anyone beyond the limits of his own territory and that the ownership of the book remains in the hands of the publishers until actually delivered and paid for by the subscribers for whom it was intended and ordered.”

By virtue of this agreement this book remains our property until delivered to the bona-fide subscriber, who has purchased it under a contract for personal use and not for resale, as contained in our prospectus. Ownership in it reverts to us if used by subscriber for any other purpose; besides he becomes legally liable for any damages done us or our business by transfer.

If, therefore, any copy is sold or delivered by the agent to dealers or other persons for resale or exposure in public libraries or for purposes other than private use, he transfers property that does not belong to him, for which offence both agent, subscriber, bookseller, or receiver are liable.

In case any book is found in a bookstore, dry-goods store, public library or other place it will be easy to determine by Thayer and Col., publishers, Boston, Mass. reference to our records into whose hands the book was given and we will at once call the guilty parties to account. Each book contains a stamp of the Publishers & Booksellers’ Protective Association, registered and numbered consecutively, placed in plain sight onside of the cover and a corresponding stamp so placed and combined with the book that the mark cannot be erased or tampered with without destroying the book. We keep a record of these numbers and so will know to whom each individual book has been consigned.

In case any book is found in a bookstore, dry-goods store, public library or other place it will be easy to determine by Thayer and Col., publishers, Boston, Mass. reference to our records into whose hands the book was given and we will at once call the guilty parties to account. Each book contains a stamp of the Publishers & Booksellers’ Protective Association, registered and numbered consecutively, placed in plain sight onside of the cover and a corresponding stamp so placed and combined with the book that the mark cannot be erased or tampered with without destroying the book. We keep a record of these numbers and so will know to whom each individual book has been consigned.

We do not sell the book to the agent whom we employ to take subscriptions on our behalf. It is consigned and remains our property until it reaches the subscriber and is paid for by the subscriber. The agent not being the owner of the books consigned to him, cannot lawfully do anything, except deliver them to bona-fide subscribers within the territory assigned to him as specified in his certificate of agency contained in the prospect to the inspection of every subscriber. If he sells or delivers to dealers or to persons outside of specified territory, he transfers property that belongs to us and not to him.

We are able by means of the precautions here described to protect the rights of the author, agent, and subscribers. We request every person finding a copy of this book in any store or public library to immediately inform us, giving registered number of the book and address of place where found. Any expense incurred in this matter will be cheerfully refunded.

Unscrupulous persons may remove these pages so as to make the excuse that the above-mentioned facts were not duly brought to the notice of every party. This guarantee and notice being permanently attached to each book makes it a legal notice. Should any party remove the same from the book he will be liable for prosecution for the above-mentioned offence and also for the mutilation of a copyrighted work. In order to prevent this and to enable every purchaser to know that the book has been tampered with, we have placed a notice on a number of pages at the beginning of the work.

Trusting that all will co-operate with us to the utmost in securing the fullest possible protection, we are

Very truly yours,

A. M. THAYER & CO., Publishers,

Boston, Mass.

DEDICATORY.

To The Good And Brave Soldiers Of The Grand Army Of The Republic,

This book is dedicated by their comrade, a slight token of appreciation of the patriotic devotion to loyalty and heroism with which they endured the hardships and fought the battles of their country during the War of the Rebellion, erve its existence and perpetuity as a nation of freemen, the proudest exemplar of a people solely govern themselves, able to sustain that government as more powerful than any nation earth.

Upon our efforts and their success depended the future of free institutions as a governmental power, giving the boon of liberty to all the peoples.

Other republics have flourished for a season, been split in fragments, or merged in despotisms, and failure would have closed forever the experiment of a government by the people for the people.

THE Preface of is usually written after the book is finished, and is as usually left unread. It is not as a rule, therefore, either a convenience or a necessity. I venture to use it at the outset as a vehicle for conveying the purposes of writing this book at all.

Having lived through and taken part in a war, the greatest of the many centuries, and carried on by armies rivalling in numbers the hosts of Xerxes, and having been personally conversant with almost all, if not all, the distinguished personages having charge and direction of the battles fought, and with the political management which has established the American Republic in power, prosperity, glory, and stability unequalled of any nation of the earth, I have been very frequently called upon by those who are, in their relations to me, personal friends, and to whom I am endeared by life-long kindnesses, to give what knowledge I have of the course of conduct in the action of national politics and the causes which led up to so great results.

I have also had my attention called to consider whether it might not be well for me to give a somewhat connected narrative of matters of which I had personal cognizance, and of some of the more important of which I had personal conduct.

I have been asked to give memories and reminiscences of those matters which concern in part my private life which would interest them, and to set forth many facts and occurrences would throw light upon the history of the country, especially during the momentous period 1860-1880. The real influences by which many were governed have not, in several instances, been exhibited to the country, and the true bearing of these influences and these motives on the great struggle have not been made apparent. Finally I desire to correct much of wrong done to myself by a prejudiced representation of facts and circumstances as to my own acts in the service of the country, especially in connection with the conduct of its armies. Therefore, I have thought it but just to myself and posterity that the true facts as I know them should be brought out.

All these considerations have compelled me to undertake at this late day of my life the labor of preparing the material necessary to be expended in writing this book, and of putting it in proper form.

Perhaps it would be well in addition to show how the book is written: Wherever facts are set out I have intended that it should be done with literal and exact accuracy, so far as they depend upon my knowledge, and in as they are exact memoranda of events; but where any fact is detailed upon the testimony of others,

I have endeavored to verify it by consulting and making known the citations of the authority in the text or in the notes. I have thought it the better way, however, to make careful examination of the accounts stated in other publications, and to draw from them in my own manner, any point which may be subject to contradiction in regard to the accuracy of the fact stated. And where I know a fact exists I say so, and where I believe it to exist from information and belief, I have given the source from which I derived that belief, if I doubt as to its truth or challenge its correctness.

Wherever opinions are expressed upon men, their character and conduct, and the motives which influenced them, they are my own opinions and I hope not capable of denial as such. Whether those opinions are correct, well founded or proper in any respect, is open to the fullest criticism.

As to my personal acts, and doings, and omissions to do, “I have in naught extenuated,” but I have reserved to myself the privilege of explaining and exhibiting my motives and feelings. In regard to others I have “set down naught in malice,” reserving to myself, however, the privilege of saying in regard to any man personally what I think it is right to say of him, however harsh the criticism may be, and of giving a true definition ofter in whatever distinct terms that criticism calls for.

In speaking of events, I have, as far as possible, put them in juxta-position, and with such bearings upon each other that they shall consist, in so far as they may, of items of history, which may aid others to reach the truth, when the time has come in the far future for the truth of history to be exactly written.

I admit frankly that this book should have been written before, so as to reap the advantage of being able to apply to my compatriots in their lifetime, and to verify the facts, as far as necessary, herein described. But being still in active business in the ardent pursuit of my profession, which has always been the pleasantest occupation of my life, I could not find the time in which it could well be done. But the delay has one ad: I have outlived most of my compatriots having to do with the events treated of, and my mind is free from almost every possible prejudice, and in a position where the temptation is strong to obey the maxim, de mortuis nil nisi bonum, so that I trust nothing will be said save where it is necessary to the cause of truth. For truth may be told, without interfering with that maxim, just as well as the facts concerning the life of Julius Caesar may be written.

Finally, I am conscious of but one regret for this delay, and that is that in the course of nature it is not probable I shall live so long as to be able to hear all the criticisms, as I am certain many will be made, upon this book, so that I can reply to them, attempting to correct everything that is wrong or mistaken in such criticisms, in justice to those that may be affected by such mistakes, as well as to answer any misstatement after made against the matter of the book, or any attempted contradiction of any fact stated therein, or any new offshoot of calumny against the author.

I hope that my days may be prolonged for such a purpose.

CHAPTER VI.

“CONTRABAND OF WAR” BIG BETHEL AND HATTERAS.

THE

day after my arrival at the fort, May 23, three negroes were reported coming in a boat from Sewall’s Point, where the enemy was building a battery. Thinking that some information as to that work might be got from them, I had them before me. I learned that they were employed on the battery on the Point, which as yet was a trifling affair. There were only two guns there, though the work was laid out to be much. larger and to be heavily mounted with guns captured from the navy-yard. The negroes said they belonged to Colonel Mallory, who commanded the Virginia troops around Hampton, and that he was now making preparation to take all his negroes to Florida soon, and that not wanting to go away from home they had escaped to the fort. I directed that they should be fed and set at work.

THE

day after my arrival at the fort, May 23, three negroes were reported coming in a boat from Sewall’s Point, where the enemy was building a battery. Thinking that some information as to that work might be got from them, I had them before me. I learned that they were employed on the battery on the Point, which as yet was a trifling affair. There were only two guns there, though the work was laid out to be much. larger and to be heavily mounted with guns captured from the navy-yard. The negroes said they belonged to Colonel Mallory, who commanded the Virginia troops around Hampton, and that he was now making preparation to take all his negroes to Florida soon, and that not wanting to go away from home they had escaped to the fort. I directed that they should be fed and set at work.

On the next day I was notified by an officer in charge of the picket line next Hampton that an officer bearing a flag of truce desired to be admitted to the fort to see me. As I did not wish to allow officers of the enemy to come inside the fort just then and see us piling up sand bags to protect the weak points there, I directed the bearer of the flag to be informed that I would be at the picket line in the course of an hour. Accompanied by two gentlemen of my staff, Major Fay and Captain Haggerty, neither now living, I rode out to the picket line and met the flag of truce there. It was under charge of Major Carey, who introduced himself, at the same time pleasantly calling to mind that we last met at the Charleston convention. Major Carey opened the conversation by saying: I have sought to see you for the purpose of ascertaining upon what principles you intend to conduct the war in this neighborhood. I expressed my willingness to answer, and the major said: I ask first whether a passage through the blockading fleet will be allowed to families and citizens of Virginia who desire to go North to a place of safety.

The presence of the families of the belligerents, I replied, is always the best hostage for their good behavior. One of the objects of the blockade is to prevent the admission of supplies and provisions into Virginia while she is hostile to the government. Reducing the number of consumers would necessarily tend to defeat the object in view. Passing a vessel through the blockade would involve so much trouble and delay, by way of examination to prevent frauds and abuse of the privilege, that I feel myself under the necessity of refusing.

Will the passage of families desiring to go North be permitted? asked Major Carey.

With the exception of an interruption at Baltimore, which has now been disposed of, travel of peaceable citizens through to the North has not been hindered; and as to the internal line through Virginia, your friends have, for the present, entire control of it. The authorities at Washington will settle that question, and I must leave it to be disposed of by them.

I am informed, said Major Carey, that three negroes belonging to Colonel Mallory have escaped within your lines. I am Colonel Mallory’s agent and have charge of his property. What do you mean to do with those negroes?

I intend to hold them, said I.

Do you mean, then, to set aside your constitutional obligation to return them?

I mean to take Virginia at her word, as declared in the ordinance of secession passed yesterday. I am under no constitutional obligations to a foreign country, which Virginia now claims to be.

But you say we cannot secede, he answered, and so you cannot consistently detain the negroes.

But you say you have seceded, so you cannot consistently claim them. I shall hold these negroes as contraband of war, since they are engaged in the construction of your battery and are claimed as your property. The question is simply whether they shall be used for or against the Government of the United States. Yet, though I greatly need the labor which has providentially come to my hands, if Colonel Mallory will come into the fort and take the oath of allegiance to the United States, he shall have his negroes, and I will endeavor to hire them from him.

Colonel Mallory is absent, was Major Carey’s answer.

We courteously parted. On the way back, the correctness of my law was discussed by Major Haggerty, who was, for a young man, a very good lawyer. He said that he doubted somewhat upon the law, and asked me if I knew of that proposition having been laid down in any treatise on international law.

Not the precise proposition, said I; but the precise principle is familiar law. Property of whatever nature, used or capable of being used for warlike purposes, and especially when being so used, may be captured and held either on sea or on shore as property contraband of war. Whether there may be a property in human beings is a question upon which some of us might doubt, but the rebels cannot Contraband of War. Col. Mallory’s three negroes before Gen. Butler at Fortress Monroe. take the negative. At any rate, Haggerty, it is a good enough reason to stop the rebels’ mouths with, especially as I should have held these negroes anyway.

Col. Mallory’s Three Negroes before Gen. Butler at Fortress Monroe.

At headquarters and in the fort nothing was discussed but the negro question, and especially this phase of it. The negroes came pouring in day by day, and the third day from that I reported the fact that more than $60,000 worth of them had come in; that I had found work for them to do, had classified them and made a list of them so that their identity might be fully assured, and had appointed a commissioner of negro affairs to take this business off my hands, for it was becoming onerous.

I wrote the lieutenant-general that I awaited instructions but should pursue this course until I had received them. On the 30th I received word front the Secretary of War, to whom I had duplicated my letter to General Scott. His instructions gave me no directions to pursue any different course of action from that which I had reported to him, except that I was to keep an accurate account of the value of their work.

But the local effect of the position taken was of the slightest account compared with its effect upon the country at large. The question of the disposal of the slaves was one that perplexed very many of the most ardent lovers of the country and loyal prosecutors of the war. It afforded a groundwork for discussion which yielded many excuses for those who did not desire the war to be carried on. In a word, the slave question was a stumbling-block. Everybody saw that if the work of returning fugitive slaves to their masters in rebellion was imposed upon the Union troops, it would never be done; the men would simply be disgusted and finally decline the duty. Our troops could not act as a marshal’s posse in catching runaway negroes to return them to their masters who were fighting us at the same time. What ought to be done? Nobody made answer to that question. Fortuitously it was thrust upon me to decide what must be done then and there, and very fortunately a few moments’ thought caused to flash through my mind the plausible answer at least to the question: What will you do? I do not claim for the phrase contraband of war, used in this connection, the highest legal sanction, because it would not apply to property used or property for use in war, as would be a cargo of coal being carried to be burned on board an enemy’s ship of war. To hold that contraband, as well might be done, by no means included all the coal in the country. It was a poor phrase enough; Wendell Phillips said a bad one. My staff officer, Major Winthrop, insisted it was an epigram which freed the slaves. The truth is, as a lawyer I was never very proud of it, but as an executive officer I was very much comforted with it as a means of doing my duty.

The effect upon the public mind, however, was most wonderful. Everybody seemed to feel a relief on this great slavery question. Everybody thought a way had been found through it. Everybody praised its author by extolling its great use, but whether right or wrong it paved the way for the President’s proclamation of freedom to the slaves within eighteen months afterwards.

There has been, so far as I know, in the several histories, but one very belittling account of the origin of this method of disposing of captured slaves used in war, and that one is the emanation of malice and ignorance in Abraham Lincoln, a history, a book which was written by one man with two pens. Mr. John Hay says : —

Out of this incident seems to have grown one of the most sudden and important revolutions in popular thought which took place during the whole war. General Butler has had the credit of first pronouncing the opinion formulating the doctrine, that under the course of international law the negro slaves, whose enforced labor in battery building was at the time of superior military value to the rebels, are manifestly contraband of war, and as such confiscable by military right and usage. There is no word or hint of this theory in his letter which reports the Mallory incident, nor any other official emanation of it by him until two months afterwards, when he stated casually that he had adopted such a theory. Nevertheless it is very possible that the idea may have come from him, though not at first in any authentic or official form. It first occurs incidentally in a newspaper letter from Fortress Monroe of the same date of the Mallory incident: Again, the negro must now be reported as contraband, since every able-bodied negro not absolutely required on the plantation is impressed by the enemy into military service as a laborer on the various fortifications.

Whether the suggestion was struck out in General Butler’s interview with the flag bearer, or at general mess table in a confidential review of the day’s work; or whether it originated with some imaginative member of his staff, or was contributed as a handy expedient by the busy brain of a newspaper reporter, will, perhaps, ever remain a historical riddle.

This double-named historian has stepped out of his way to attempt to rob me of the authorship of this theory of disposing of such captured slaves. As he evidently did not understand the matter about which he was speaking, he has noted the fact that I did not ask, in my letter to General Scott the morning after I met Colonel Mallory’s agent, as to this theory or use the word contraband, and has produced it as evidence that the phrase was not used by me in the interview as to captured slaves. If he had read my letters to General Scott he would have seen that I was asking from him instructions how to deal with the whole question of negro slavery during the war.

As I have already said, I have never claimed and never believed that contraband alone would cover that. That was the popular belief, not mine. I was asking Scott for instructions as to what I should do with the slave men, women, and children, sick and well, who came to me. I did not need any instructions from Scott or Cameron, neither of whom were lawyers, as to the legal question of the law of nations concerning captured slaves when used by their masters in actual warfare.

The question put and argued in those letters was: What was I to do with the slave population of the whole country who came to me voluntarily, men, women, and children. I had $60,000 worth of them. That question included the slaves of loyal men. In this matter I wanted the sanction of the government.

I had adopted a theory on this question for myself in Maryland, and got rapped over the knuckles for it by Governor Andrew. I had learned what manner of man Scott was, and I was desirous to take instructions from him for my action but not for my law.

If Mr. Hay had stopped at the point where he was led to doubt my authorship of contraband because I had not mentioned it to Scott, and was so misled, no more would need to be said. The sin of ignorance God winks at, and I should follow that example.

But having been a newspaper man himself, and this being a great question of international law, which has never yet been settled, and which, as he argues, contributed largely to the freeing of the slaves, he goes on to suggest that probably it was written by a newspaper reporter, because he finds the whole theory stated in a newspaper letter written at night after my return to the fort.

The whole matter of the interview with the flag of truce officer was the common talk of all, and the reporter was writing the current news. Yet Mr. Hay suggests it might have come from an imaginative staff officer. Why a staff officer ? Mr. Hay, this was a matter of the laws of war. As the general was supposed to have some knowledge upon that subject, why didn’t you state in your History that you thought it probable the general arrived at such a conclusion of law rather than it should have originated with an imaginative staff officer or be contributed as a handy expedient by the busy brain of a newspaper reporter ?

If Mr. Hay had desired to write History and not simply to make a book suggesting historical riddles, he could easily have ascertained regarding the matter by writing a simple note either to Major Carey, who is an honored citizen of Richmond, Va., or to his associates bearing that flag, or to myself. If he had put the question to me I should have answered: A poor thing, sir, but mine own. If he had inquired of Major Carey, that gentleman would have answered that contraband was the ground upon which I refused to release Mallory’s slaves and that we then discussed the whole question together.

Mr. Hay, read this: —

Richmond, Va., March 9, 1891.

Gen. Benj. F. Butler, Washington, D. C.:

Dear Sir: — I have received, through a friend, your request to furnish a detailed statement of the facts in regard to the introduction of the term contraband, as applied to the slave population of the United States, about the beginning of our Civil War; and as my recollection is very distinct, I give it for whatever it may be worth to you as to the truth of history.

The term was employed by you at a conference held between us, on the Hampton side of Mill Creek Bridge, on the evening of May 24, 1861, the day after Virginia had voted on the ordinance of secession, but before the ratification (though anticipated) was definitely known. I was then in command, at Hampton, of four volunteer companies of about two hundred men (one of them artillery without guns), very poorly equipped, and almost entirely without ammunition, who had never been in camp, and who dispersed to their homes in the town and neighborhood every night; and you were in command of the United States troops (said to be about ten thousand) at Fortress Monroe. As there were no Virginia troops at that time between Hampton and Richmond (a distance of ninety-six miles), save three companies of infantry at Yorktown, and two companies, perhaps, organizing at Williamsburg, and as it was thus evidently important for us to preserve the peace, I had instructions from General Lee, then commander-in-chief of the Virginia troops, to avoid giving any provocation for the commencement of hostilities; to retire before your advance, if attempted; and to obstruct, as far as possible, your progress by burning bridges and felling trees across the public roads, until reinforcements could be sent to Yorktown. At night, after the election (May 23), Col. C. K. Mallory, of the One Hundred and Fifteenth Virginia Militia (with other citizens), called at my headquarters, and asked me to take some steps for the recovery of one of his slaves, who had escaped to Old Point, and had been held there by you, and put to work in the service of the government. I promised to do what I could, and accordingly sent to you, next morning, a communication under flag of truce (the first I believe of the war), deeming that course advisable in view of the critical condition of affairs, and asked for a conference with you, which was promptly granted, 3.30 the same day and Mill Creek Bridge being named as the time and place of meeting.

We met at the time and place appointed, and for several hours riding up Mill Creek to its head, and back again, via Buck Roe, by a slight detour to Fort Field Gate, we discussed many questions of great interest (to me at least), among them the return of fugitive slaves who had gone within your lines. I maintained the right of the master to reclaim them, as Virginia (so far as we knew) was a State of the Union; but you positively refused to surrender them (or any other property which might come into your possession), claiming that they were contraband of war; and that all such property would be turned over to your quartermaster, who would report to the government, to be dealt with as might be subsequently determined. Failing in the accomplishment of my mission, we parted when it was quite dark, and returned to our respective posts.

I have frequently mentioned these facts, with many other incidents of the conference (some serious and some amusing) to members of my family and friends; and as it was the first time I had ever heard the term contraband so used, I have always given you whatever credit might attach to its origin.

Respectfully, your obedient servant,

M. B. Carey.

If Mr. Hay had looked in the New York Tribune, of which he was once editor, he would have found a letter written that day at Fortress Monroe, after I had my interview with Major Carey, and in that letter he would have read the following: —

Three slaves, the property of Colonel Mallory, commander of the rebel forces near Hampton, were brought in by our picket guard yesterday. They reported that they were about to be sent South, and hence sought protection. Major Carey came in with a flag of truce and claimed their rendition under the fugitive slave law, and was informed by General Butler that under the peculiar circumstances he considered the fugitives contraband of war, and had set them to work inside the fortress.

Mr. Hay, you do not speak of anybody who ever said anything to the contrary of the “contraband” thought being mine: why not, if you ever heard anything to the contrary? Upon the whole do you not think this exhibition of facts which I have made as to the manner of your writing “History” shows that you wrote very carelessly and negligently your “History” of Abraham Lincoln? If it is all written like this specimen, — for I have not read it all because I know more about Abraham Lincoln than you ever did, — God help poor Lincoln’s memory thus to go down to posterity. You can’t weigh a load of hay with fish scales, you know.

Speaking of phrases, they will stick to the man they belong to. This one will stick to me in spite of all efforts to the contrary, and I know of another phrase which will stick to you in spite of all yours, because no Christian gentleman will ever claim it, and no man of good literary taste will ever permit it to be ascribed to him. The phrase I refer to is the only thing that ever made your poem “Little Breeches” famous, while making, perhaps, its author infamous: —

I made requisition on General Scott for horses, for artillery, for wagons, and for tents and camp equipage, as my command was largely unprovided for in that regard. At last I sent my brother to Washington to get authority to buy some. He got it, and went to Baltimore and bought one hundred and twenty-five very good horses. Meanwhile I had sent to my home for nine horses of my own, which were coming as soon as they could be got there. Orders were left that the horses obtained by my brother should be sent on after him to Fortress Monroe; but he was not an old campaigner, and did not know that there were as many horse thieves in the army as there were out of it. The next day, his horses not coming, he went to see what the matter was, and found that one hundred and odd had been taken to Washington, so it was very lucky that mine from home had not got there. This loss of horses for my artillery was of very serious consequence to me and a serious loss to the country. If I could have had a few horses so that I could have mounted my artillery and picked out a few of my best soldiers Marching contrabands to work at Fortress Monroe. From a drawing. for cavalry under an experienced cavalry officer, and thus have had the ground reconnoitred and some guns served to meet the enemy’s guns at the time of the attack on Big Bethel, that encounter would have resulted in an entirely different way and in perfectly certain victory for the United States troops.

There was a point nine miles from the fort and on the road leading from Hampton to Yorktown, which I learned the rebels intended to entrench and hold, because they expected a move towards Richmond to be made very soon. The insane cry of On to Richmond had been continually sounded by Mr. Greeley and his coadjutors. After carefully reconnoitring the position, I concluded upon an attack.

A creek crossed the road close by the church known as the Bethel. The bridge over this creek was attempted to be commanded by a slight fortification some half a cannon-shot distance beyond. Col. D. H. Hill, of North Carolina, held it with five hundred men. Our negro scouts reported them two thousand in number, and they really thought there were as many as that, for a negro scout had to be a veteran in the war before he learned that two hundred men were not a thousand, and that five hundred were not two thousand. So upon the point of numbers I was satisfied; and I was further convinced that there were no more than one thousand in Yorktown, that might possibly come to Bethel, as they afterwards did.

After the most careful and thorough preparation, and a personal reconnoissance of the lay of the country by Major Winthrop, I came to the conclusion to attempt to take this post, and I drew up with his aid the following order for the detail of the movement : —

A regiment or battalion to march from Newport News, and a regiment to march from Camp Hamilton, — Duryea’s. Each will be supported by sufficient reserves under arms in camp, and with advanced guards out on the road of march.

Duryea to push out two picket posts at 10 P. M.; one two and a half miles beyond Hampton, on the county road, but not so far as to alarm the enemy. This is important. Second picket half as far as the first. Both pickets to keep as much out of sight as possible. No one whatever to be allowed to pass out through their lines. Persons to be allowed to pass inward toward Hampton, unless it appears that they intend to go roundabout and dodge through to the front.

At 12, midnight, Colonel Duryea will march his regiment, with fifteen round cartridges, on the county road towards Little Bethel. Scows will be provided to ferry them across Hampton Creek. March to be rapid, but not hurried.

A howitzer with canister and shrapnel to go.

A wagon with planks and material to repair the Newmarket bridge.

Duryea to have the two hundred rifles. He will pick the men to whom to entrust them.

Rocket to be thrown up from Newport News. Notify Commodore Pendergrast of this to prevent general alarm.

Newport News movement to be made somewhat later, as the distance is less.

If we find the enemy and surprise them, men will fire one volley, if desirable, not reload, and go ahead with the bayonet.

As the attack is to be by night, or dusk of morning, and in two detachments, our people should have some token, say a white rag (or dirty white rag) on the left arm.

Perhaps the detachments who are to do the job should be smaller than a regiment, three hundred or five hundred, as the right and left of the attack would be more easily handled.

If we bag the Little Bethel men, push on to Big Bethel, and similarly bag them. Burn both the Bethels, or blow up if brick.

To protect our rear in case we take the field-pieces, and the enemy should march his main body (if he has any) to recover them, it would be well to have a squad of competent artillerists, regular or other, to handle the captured guns on the retirement of our main body. Also spikes to spike them if retaken.

George Scott to have a “shooting iron.”

Perhaps Duryea’s men would be awkward with a new arm in a night or early dawn attack, where there will be little marksman duty to perform. Most of the work will be done with the bayonet, and they are already handy with the old ones.

There was a small negro church called Little Bethel which stood in advance of Great Bethel a short distance. That was in no way fortified, and sheltered a few men.

I could not go with the command myself and it was not proper that I should; but I selected as commander my officer next in rank, General Pierce, of Massachusetts. I very much wished to devolve the command on Colonel Phelps as certainly the more competent officer, but there were unfortunately one or two colonels outranking him that were no more qualified than General Pierce, and I did not like to do these officers an apparent injustice. Besides I did not deem the enterprise at all difficult.

Newport News was nearer Bethel, and my proposition was that the regiment there should start later than the two regiments from Camp Hamilton, and that at a well-known junction of the road they should meet, advance as fast as possible, capture Little Bethel, which could easily be done, and then all make an assault at daylight upon the entrenchments at Great Bethel. To be sure of having the march properly timed, I ordered the signal to be given at Newport News. There were four very small howitzers which were to be drawn by the men, for want of horses to take up larger guns.

With six of our men to one of the enemy I could not conceive how there could be any possibility of not marching at once over the works; and if the troops had marched steadily forward the rebels would not have stayed a minute.

Everything was utterly mismanaged. When the troops got out four or five miles to the junction where the regiments were to meet, it being early dawn and the officers being very much scared, Colonel Bendix mistook the colonels and staff of the other regiment for a body of cavalry, and fired upon them. The fire was returned; and by that performance we not only lost more men than were lost in the battle, but also ended all chance for a surprise.

The two regiments marched forward, the main force remaining behind. Duryea took Little Bethel, which had been abandoned. With two hundred rifle-men supporting Greble and his cannon, Duryea went forward with his Zouaves to a piece of timber, and opened fire in answer to the enemy’s artillery. Greble advanced his guns within three hundred yards of the enemy’s battery. He was pretty soon left by the Zouaves, who took shelter in the woods. That was no harm, as nobody came out from the entrenchments to disturb him. He silenced one of the enemy’s guns, and substantially all of them, when by the last discharge of a gun by the enemy he was instantly killed.

From that time there did not seem to be a head more than a cabbage head to undertake to do anything, except it might be Winthrop. Greble held his position an hour and a half, while the main body of the troops stood about a half mile from his position waiting for the officers to form a plan of battle. They carefully disobeyed orders, which were, as has been seen, to go right ahead with fixed bayonets and fire but one shot, and they did not do even that. If they had only marched steadily forward, as I have said before, the enemy would have fled.

The plan that they at last agreed upon was well enough, only an exceedingly contrary one. They decided not to attack the rebel position in front, but to endeavor to go around it. Therefore it was agreed that Duryea should hold his place where it was, in apparent support of Greble’s battery; that Colonel Townsend should march obliquely to the left beyond the woods so that he might strike the Yorktown road and attack the enemy in his rear and cut him off from Yorktown; that at the same time Bendix should march by his flank obliquely to the right and then go across a little stream easily fordable, and form a junction with Townsend in the rear of the enemy’s entrenchments; and that would result either in the enemy taking flight or being captured.

But as Townsend moved up, a portion of his command got a little ahead of him on the other side of a stone wall. When he saw them, he took them for a body of the enemy trying to flank him, and at once concluded to retire. He did retire, leaving Winthrop near the fort in expectation of instant victory. Winthrop did not know that the order had been given for the retirement of Townsend’s troops. Winthrop sprang upon a log to take a view of the situation, and see how matters stood. He was supported by one private. All the rest of his support had retired under orders. As he stood up in full view, a rifle shot from the enemy killed him instantly. Meantime Duryea and Bendix were trying to pass to the left of the enemy’s entrenchments to be ready to spring upon them when Townsend had got to his position; and that was all that was done.

A council was called and all the colonels but Duryea voted to retire, and Pierce gave the order. The ground it was put upon was that the troops with long marching were hungry. They had actually marched eleven miles; and if Pierce had given the order for them to sit down and take lunch, the enemy would have run away (as is now known they did do), because they would have supposed we had come to stay. A few volunteers headed by Lieutenant-Colonel Warren remained on the field until they could pick up all the wounded. They brought off Greble’s gun, and then had to drag the wounded in wagons nine miles.

Upon the return to the fort the stories that were brought back were sufficient evidence of the great alarm. Pierce said that there were between four and five thousand of the enemy.

These statements will perhaps be better summed up in the way they finally got into the Northern press, through a communication addressed to me: —

Men cannot be required to stand in front of a rampart thirty feet high, before the muzzles of mounted guns, loaded with grape and canister and musket balls, doing nothing. When they are commanded to march through fire and reach the ditch, they must be provided with the means to cross it, or jump into it, and sticking their bayonets into the slope of the scarp, form with them ladders by means of which the more active can mount the parapet. But before men are sent into a position — recollecting that every ditch will be swept by a flank fire — they must not only be instructed in their duties, but supported by a steady fire upon the enemy.

As a specimen of the stories reported back, I have a vivid memory of an extraordinary one told me by one of the bravest young men I ever knew. He was then not even a private in the army, but he begged of me the privilege of going with the expedition and carrying a musket. His father was a warm friend of mine and I took his son in my charge when I first started, using him as a sort of private secretary to take care of my papers and copy some of them. I afterwards appointed. him a lieutenant when I raised my troops for the New Orleans expedition. He went down there with me, became a very efficient officer, distinguished for bravery and dash, and in two years was made a brigadier-general for his defence of one of the forts on the Mississippi River against a very superior force of the enemy. He was a very level-headed gentleman in every particular. I think I left him in the Department of the Gulf as a lieutenant-colonel. There his promotions were got under other commanders. Yet in the evening of that day at Great Bethel, after I had spent several hours hearing all sorts of stories, he came into my office and said: —

“General, do you want me to tell you anything of the fight up at Great Bethel?”

“Yes, I do,” said I; “I have heard nothing but the account of men who seem to have been frightened almost to death. I don’t believe you were.”

“But I was, General, yet I think I can tell you what I saw. I cannot tell you anything about the two regiments shooting at each other going up, because I was not there at that time; I was with Duryea’s regiment. Well, we took Little Bethel, and that was not anything to take; the rebels had run away. Then we marched up into the woods to support Greble’s battery, and we remained there a while. As we came up to the woods the enemy began to fire at us and the balls at first went over our heads into the trees. Well, we could have stood that, but, General, they fired ‘rotten balls.’”

“You mean shells, I suppose?”

“Well, yes; that is what they told me afterwards they were; but they would strike a tree and burst, and the pieces would drop around among us. I guess if they had been regular balls the men would have stood it, but they broke and scattered to the woods. It seemed as if they might as well scatter as anyway; because there was nobody came out of the fort at us.”

“Well,” said I, “I am glad to see a man who got near enough to see what the fort was.”

It was a very large fort, I should think some thirteen feet high, and they had mounted on it some fifteen or twenty guns. There was a ditch in the front, and if we had got up to it it would have been impossible for us to have climbed up so as to get in it.

“Do you know anybody that got nearer to it than you?”

“No; there were some as near. But Winthrop went clear up farther than any of us, and then he. went back to the main body of the troops.”

That was the least exaggerated report that I got of the fort. Some reported as many as thirty guns. As a matter of fact, there were three six-pounder field-pieces, and the fortification was so low that they had to dig an excavation to let the wheels down so as to bring the top of the parapet above the top of the gun carriages so as to protect them from our fire. Afterwards I rode my horse at full trot over those thirteen feet high parapets.

I sent quite early in the evening to have George Scott, who was to have a “shooting iron” and accompany Winthrop, and found him The contraband of War. meeting of Gen. Butler and Maj. Carey at Union picket lines next Hampton. mourning bitterly for his loss. I asked him if he was afraid to go up that night to Big Bethel and see who were there and how many there were. He said he would go up, and I gave him a light basket containing some restoratives and bandages if he should find any wounded. He started with alacrity. I told him to get back as soon as he could, and to have me called at whatever hour of night. Returning before daybreak he reported to me, and from the nature of the report, I had no doubt of its truth. He had gone on to the field, and had looked around in the woods to see if he could find any wounded or dead men, but found none. He crept up carefully near the works and listened to hear any noise of a sentinel or anybody. Not hearing anything, he cautiously advanced until he got up to the breastwork, and then, after carefully looking it over, he went into the work, and found not one soul there. The enemy had retired, and nobody to this day, as far as I can ascertain, knows whether the rebels went before our men did or afterwards.

Meeting of Gen Butler and Maj. Carey at Union Pickett Lines next Hampton.

It may be worthy of note that the same thing happened at the battle near Manassas Junction, known as the battle of Bull Run; after the fight both armies ran away, so that there was no armed force on the battle field, as I have been informed, and correctly, I believe.

It will be seen that the affair at Bethel was simply a skirmish, and not even a respectable one at that, either in the vigor of the attack or in the loss of men. We lost quite as many men by the fire of Colonel Bendix upon Colonel Townsend’s regiment of foot, mistaking it for cavalry, as we lost altogether at Bethel.

When the plan of the expedition became fully known and the condition of the place which was to be attacked was ascertained, nobody criticised the movement, as there were two regiments to go into the fight with a brigadier-general in command. I had but one brigadier-general, General Pierce, and I had to give him the command. Yet while no blame could seem to attach to me, a senseless cry went out against me, and it almost cost me my confirmation in the Senate. Of course every Democrat voted against me, and so did some of the Republicans, for various reasons. I suppose I should have failed of confirmation if Colonel Baker, then senator from Oregon, who had been detailed to do duty with me at Fortress Monroe, had not been in his seat and explained the senselessness of the clamor. But one senator from my own State voted for me, the other, the senior senator, voting against me because of my difference with Governor Andrew on the slave question.

In the meantime neither horses nor artillery came. I did, however, get a very valuable reinforcement of a California regiment and a half, at the head of which was Colonel Baker, who had had some experience in Mexico as an officer. We agreed to attempt, as soon as our horses and artillery should come, an expedition that would reflect credit on both of us, and we determined that neither should blame the other if it failed, because both would go together.

I asked, on the 23d of May, for a few artillery and cavalry horses with their equipments. These were not received from Washington until July 21, and then only after every possible exertion on my part even to the extent, as we have seen, of causing them to be bought by my own agent and having them brought on to Washington.

This was not negligence, as I at first supposed, but studied unjust treatment. I should not venture to say this did I not have it in a letter from a man in Washington who knew everything that was done about army headquarters, — a bold soldier, an officer, a general. As he is yet alive I do not give his name; but the letter has been published now more than a quarter of a century and no man has ever dared to question it. It is as follows: —

June 8th I received your letter and despatch, and, contrary to your orders, I read both to the President, under the seal of confidence, however. I have told him that ——— would never let you have any troops to make any great blow, and I read the despatch to show that I understood my man. He intended to treat you as he did ——— , and as he has always treated those whom he knew would be effective if he gave them the means, retaining everything in his own power and under his own immediate control, so as to monopolize all the reputation to be made.

I have been a little afraid lest you might attempt more than your means justified, under the impression that you would otherwise disappoint, the country. But I am pleased to see that you have not made this mistake. You must work on patiently till you feel yourself able to do the work you attempt, and not play into your enemies’ hands, or those of the miserable do-nothings here, by attempting more than in your cool judgment the force you have can effect. You will gradually get the means, and then you may make an effective blow. Unfortunately, indeed, the difficulties increase as your force increases, if not more rapidly. We have forty thousand men, I believe, and provisions and transportation enough to take them to Richmond any day, and yet our lines do not extend five miles into Virginia, where there are not, in my opinion, men enough to oppose the march of half the number to Richmond. Old ——— is at ——— with twenty thousand men, and is moving as cautiously towards the Potomac as if the banks were commanded by an army of Bonaparte’s best legions, instead of a mob, composed for the most part of men who will only wait for an opportunity to desert a flag they detest. This war will last forever if something does not happen to unseat old ———. ——— in the West, with sixty thousand men under canvas, has not made a movement except let a few regiments march up the Baltimore & Ohio railroad, at the urgent solicitations of the people. So we go. Congress will probably catch us without our having performed any service worthy of the great force we have under pay.

I grumble this way all the time, and to everybody, in the hope that I may contribute to push on the column. I am very much in hopes we shall be pushed into action by the indignation of the people, if not by our own sense of what is due to the cause we have taken in hand.

On the day that I received my horses and artillery and was preparing to start on our expedition, the battle of Bull Run was fought. I had ascertained before, from a private source, that I was not to have any aid before the battle of Bull Run, and that some of my troops were to be withdrawn. Immediately after that battle, which was predestined to disaster on our side, as I shall take leave to make plain hereafter, an order came on the 24th of July that all my effective forces should be removed to Baltimore together with Colonel Baker. They had become so frightened at Washington that they supposed the secessionists of Baltimore would rise, while there was no more danger of it than there was of an outbreak at Boston. In fact, there never was at any time during the war so much of an outbreak at Baltimore as there was at Boston when the draft riots occurred; and that Boston outbreak was put down by a young officer of mine, Lieutenant Carruth, with two pieces of artillery, served by men who had not yet been mustered into service.

Of course this move of Scott ended all hope or expectation that anything further would be allowed to be done at Fortress Monroe. To make it sure that nothing more would be done, as Scott thought, he soon afterward sent a man to relieve me from command that could not do anything but simply occupy the position of commander of that department, and leave me to do the work, and restrain me from doing anything.

General Wool’s condition and Scott’s knowledge of it will appear in the following correspondence: —

Fortress Monroe, August 8, 1861.

Col. Thomas A. Scott, Assistant Secretary of War:

Dear Sir: — May I ask if you have overlooked the order signed by the President for the raising of five thousand troops? I pray you get this thing through for me, and I will be obliged forever and ever. I am losing good daylight, now that the three months men are being disbanded. Can you not add this to the many kind courtesies of our friendship?

Truly yours,

Benj. F. Butler.

Headquarters of the Army, August 8, 1861.

Major-General Wool, U. S. A., Troy, N. Y.:

It is desirable that you repair to and assume command of the department of which Fortress Monroe is the place of headquarters. It is intended to reinforce that department (recently reduced) for aggressive purposes. Is your health equal to that command? If yes, you will be ordered thither at once. Reply immediately.

Winfield Scott.

Headquarters Department of Virginia,

Fortress Monroe, August 11, 1861.

Lieutenant-General Winfield Scott:

General: — I have the honor to report the safe return of an expedition under Lieutenant Crosby, of my command, upon the Eastern shore, for the purpose of interrupting the commerce between the rebels of Maryland and their brothers in Virginia. I also enclose herewith a copy of a report of a reconnoissance of the position of the enemy, made from a balloon. The enemy have retired a large part of their forces to Bethel, without making any attack upon Newport News. I have nothing further of interest to report except the reception this morning of an order that Brevet Major-General Wool is directed by the President to take command of the Department of Virginia.

I have the honor to be, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

Benj. F. Butler,

Major-General Commanding.

There had been great complaint in the New York Times that General Wool had not been given some place where his great experience would have a fair chance to benefit the country. It was argued by the Times in an editorial after the battle of Bull Run, that there should be a dictator who should take Lincoln’s place and carry on the war, and that George Law should be that dictator. As this was not done at once, there was a cry that the great State of New York should have another major-general in the army. It was urged that there was in New York a major-general of the regular army — General Wool — who had lived for a great many years in a state of retiracy, and that he should have a command in the army suited to his rank, and that it was the duty of the President to have him assigned to such command.

Now, the President well knew that General Wool could not do anything, simply because he was too old and infirm, a fact that he knew as well as anybody. It was evident, too, from Scott’s letter that he also knew it, because he wrote Wool telling him that if his health would allow it, it would be desirable that he should be sent to Fortress Monroe. Thereupon Wool came there; but there was no order to relieve me, and I was not at liberty to leave the department.

Wool got there on the 17th of August, and I turned over the command to him. There was nothing I could complain of. A very much older soldier, and a very efficient military officer when he was younger, was ordered to command in my department; and although he had been assigned only to the Department of South Eastern Virginia, yet I supposed that meant the whole Department of Virginia and North Carolina. At any rate, I did not choose to struggle on that point, and so I turned over the command to him, using these words: — “No personal feelings of regret intrudes itself at the change in the command of the department, by which our cause acquires the services in the field of the veteran general commanding, in whose abilities, experience, and devotion to the flag, the whole country places the most explicit reliance, and under whose guidance and command, all of us, and none more than your late commander, are proud to serve.”

Thereupon General Wool, who was lieutenant-general by brevet, immediately put me in command of all the troops in the department except the regulars.

Headquarters Department of Virginia,

Fortress Monroe, Va., August 21, 1861.

Special Order No. 9.

Major-General B. F. Butler is hereby placed in command of the volunteer forces in this department, exclusive of those at Fortress Monroe.

His present command at Camps Butler and Hamilton will include the First, Second, Seventh, Ninth, and Twentieth New York Regiments, the Battalion of Massachusetts Volunteers, and the Union Coast Guard, and the Mounted Rifles.

By command of Major-General Wool:

C. C. Churchill,

First Lieutenant, Third Artillery,

Actg. Asst. Adjt.-Gen.

To show what General Wool thought as to my not having done any more, I take leave to transcribe his first letter to General Scott, August 24, three days after he was put in command: —

Headquarters Department of Virginia,

Fortress Monroe Va, August 24.

Lieutenant-General Winfield Scott, General-in-chief:

General: — Allow me to ask your attention to the condition of the troops in this garrison. Of seven companies of artillery we have but six officers. It is reported to me that seven of the artillery officers have been appointed in the quartermaster’s and commissary departments. I have been compelled to take Captain Churchill for assistant adjutant-general. This leaves but five artillery officers. Notwithstanding, however, Captain Churchill, although his duties are exceedingly onerous, attends to the duties of his company. From this circumstance, not finding a volunteer officer fit for the duty, I have been compelled to take Captain Reynolds, of the Topographical Engineers, for aide-de-camp, which I request may be approved. I require two more, as the assistance of Captain Reynolds is indispensable in the office of the acting assistant adjutant-general.

The Tenth New York Regiment is attached to the garrison of Fortress Monroe, but is wholly unfit for the position. As soon as I can make the arrangements, I intend to exchange this regiment for another and a better one.

To operate on this coast with success (I mean between this and Florida) we want more troops. At any rate, I think we ought to have a much larger force in this department. If I had twenty or twenty-five thousand men, in conjunction with the navy, we could do much on this coast to bring back from Virginia the troops of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia; but the arrangements should be left to Commodore Stringham and myself. I do not think it can be done efficiently at Washington. We know better than anyone at Washington attached to the navy what we require for such expeditions.

I have the honor to be, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

John E. Wool,

Major-General.

My friends, a great many of them, were very much disturbed by this position of things. They said that this action of General Scott was intended to slight me; that I was made second in command, and that I ought to resign at once and go home, and the people would set it all right; that Scott had never blamed me for the reverse of even a platoon under my command except at Bethel, and that there the movement was well planned and failed only because it had to be carried out by somebody else than myself, so that at any rate I was not to blame.

I told all my friends that I did not feel aggrieved at all; that I would beat Scott at his own game, as indeed I was already prepared to do; that he had sent Wool down without any instructions; that Wool could not go anywhere or do anything; that Wool did not like Scott any better than Scott did me; that Wool wanted all the work done by some one else while he had a nice place in the camp, and I wanted to do all the work I could do and have somebody else take the responsibility.

I had been watching the building of Fort Hatteras and Fort Clark. I had had some loyal North Carolinians for many weeks in the forts at work, and I proposed, as soon as I could, to take the forts, for they were very important. But it would be of no more use for me to ask Scott for any troops with which to do it than it would be to attempt to fly. No, he would not even let me take the troops I had or any part of them.

Therefore, as soon as General Wool got fairly in his saddle, I explained to him these matters about the forts at Hatteras, and the great necessity of taking them. Now he was an officer in the regular army and I knew would never attempt such an expedition without a great many men with him; it must be a great expedition. Therefore I said nothing to him about how many men I thought it would need. I assured him, however, that there could be no danger of any attack either upon Newport News or Fortress Monroe, because I had sent up a balloon over a thousand feet so as to examine the whole country round about, and found that Magruder had retired to Bethel and Yorktown with his troops, and given up his expedition against Newport News. This, by the way, was the first balloon reconnoissance of the war.

I also told Wool that in his assignment Scott did not mean to let him do anything any more than he did me. I set out to him the exact condition of things in regard to Hatteras, and informed him that the navy was very anxious to make the attack, and if it were done while he was in command of that department, it would result in great glory to him as the first considerable success of the war. After my consultation with him, an order was drawn as follows, which he signed: —

Headquarters Department of Virginia,

Fortress Monroe, Va., August 25, 1861.

Special Order No. 13.

Major-General Butler will prepare eight hundred and sixty troops for an expedition to Hatteras Inlet, North Carolina, to go with Commodore Stringham, commanding Home Squadron, to capture several batteries in that neighborhood. The troops will be as follows: Two hundred men from Camp Butler and six hundred from Camp Hamilton, with a suitable number of commissioned officers, and one company (B) of the Second Artillery from Fortress Munroe. They will be provided with ten days rations and water, and one hundred and forty rounds of ammunition. General Butler will report, as soon as he has his troops prepared, to Flag-Officer Stringham, and he will be ready to embark at one o’clock to-morrow. As soon as the object of the expedition is attained the detachment will return to Fortress Monroe.

Captain Tallmadge, chief quartermaster, will provide a detachment of eight hundred and sixty men for the expedition to Hatteras Inlet, with a suitable quantity of water for ten days consumption, and the chief commissary of subsistence, Captain Taylor, will provide it with rations for the same length of time. These officers will report the execution of these orders by ten o’clock to-morrow if possible.

By command of Major-General Wool:

C. C. Churchill,

First Lieutenant, Third Artillery,

Act. Asst. Adjt.-Gen.

Armed with the order we left Fortress Monroe at one o’clock on Monday, August 26. The last ship of our fleet but the Cumberland arrived at Hatteras about 4 o’clock on Tuesday afternoon. We went to work landing troops that evening and put on shore all we could, 345, when all our boats became swamped in the surf. Our flat boat was stove, and also one of the boats from the steamer Pawnee. We therefore found it impracticable to land more troops. The landing was being covered by the guns of the Monticello and the Harriet Lane. I was on board the Harriet Lane directing the landing of the troops by means of signals, and was about landing with them, when the boats were stove. We were prevented from further attempts at landing by the rising of the wind and sea.

In the meantime the fleet had opened its fire upon the nearest fort, which was finally silenced and its flag struck. No firing was opened upon our troops from the other fort, and its flag was also struck. Supposing this to be a signal for surrender, Colonel Weber, who was in command on shore, advanced his troops up the beach. By my direction the Harriet Lane was trying to cross the bar so as to get in the smooth water of the inlet, when the other fort opened fire upon the Monticello, which had proceeded in advance of us.

Early the next morning the Harriet Lane ran in shore for the purpose of covering any attack upon the troops. At the same time a large steamer was observed coming down the sound. She was loaded with reinforcements of the enemy, but she was prevented from landing. At eight o’clock the fleet opened fire on the forts again, the flag-ship being anchored as near as the depth of water allowed and the other ships coming gallantly into action. Meanwhile I went with the Fanny over the bar into the inlet. As the Fanny rounded in over the bar, the rebel steamer Winslow went up the channel having on board a large number of rebel troops, which she had not been able to land. We threw a shot at her from the Fanny, but she proved to be out of range. I then sent Lieutenant Crosby on shore to demand the meaning of the white flag which had been hoisted. The boat soon returned, bringing the following communication from Samuel Barron, late captain in the United States Navy: —

Fort Hatteras, August 29, 1861.

Flag-Officer Samuel Barron, C. S. Navy, offers to surrender Fort Hatteras, with all the arms and munitions of war; the officers to be allowed to go out with side arms and the men without arms to retire.

S. Barron,