I am now going to take this book to Lewis Squires and

ask him to write in it his account of the Buffalo hunt.

(The following is in Mr. Squires' handwriting:)

"By Mr. Audubon's desire I will relate the adventures

that befell me in my first Buffalo hunt, and I am in hopes

that among the rubbish a trifle, at least, may be obtained

which may be of use or interest to him. On the morning

of Friday, the 23d, before daylight, I was up, and in a

short time young McKenzie made his appearance. A

few minutes sufficed to saddle our horses, and be in readiness

for our contemplated hunt. We were accompanied

by Mr. Bonaventure the younger, one of the hunters of the

fort, and two carts to bring in whatever kind of meat

might be procured. We were ferried across the river in

a flatboat, and thence took our departure for the Buffalo

country. We passed through a wooded bottom for about

one mile, and then over a level prairie for about one mile

and a half, when we commenced the ascent of the bluffs

that bound the western side of the Missouri valley; our

course then lay over an undulating prairie, quite rough,

and steep hills with small ravines between, and over dry

beds of streams that are made by the spring and fall

freshets. Occasionally we were favored with a level prairie

never exceeding two miles in extent. When the carts overtook

us, we exchanged our horses for them, and sat on

Buffalo robes on the bottom, our horses following on

behind us. As we neared the place where the Buffaloes had

been killed on the previous hunt, Bonaventure rode alone

to the top of a hill to discover, if possible, their whereabouts;

but to our disappointment nothing living was to

be seen. We continued on our way watching closely,

ahead, right and left. Three o'clock came and as yet

nothing had been killed; as none of us had eaten anything

since the night before, our appetites admonished us that it

was time to pay attention to them. McKenzie and Bonaventure

began to look about for Antelopes; but before

any were 'comeatable,' I fell asleep, and was awakened

by the report of a gun. Before we, in the carts, arrived at

the spot from whence this report proceeded, the hunters

had killed, skinned, and nearly cleaned the game, which

was a fine male Antelope. I regretted exceedingly I was

not awake when it was killed, as I might have saved the

skin for Mr. Audubon, as well as the head, but I was too

late. It was now about five o'clock, and one may well

imagine I was somewhat hungry. Owen McKenzie commenced

eating the raw liver, and offered me a piece.

What others can eat, I felt assured I could at least taste.

I accordingly took it and ate quite a piece of it; to my

utter astonishment, I found it not only palatable but very

good; this experience goes far to convince me that our

prejudices make things appear more disgusting than fact

proves them to be. Our Antelope cut up and in the cart,

we proceeded on our 'winding way,' and scarcely had we

left the spot where the entrails of the animal remained,

before the Wolves and Ravens commenced coming from all

quarters, and from places where a minute before there was

not a sign of one. We had not proceeded three hundred

yards at the utmost, before eight Wolves were about the

spot, and others approaching. On our way, both going

and returning, we saw a cactus of a conical shape, having

a light straw-colored, double flower, differing materially

from the flower of the flat cactus, which is quite common;

had I had any means of bringing one in, I would

most gladly have done so, but I could not depend on

the carts, and as they are rather unpleasant companions,

I preferred awaiting another opportunity, which I hope

may come in a few days. We shot a young of Townsend's

Hare, about seven or eight steps from us, with

about a dozen shot; I took good care of it until I left

the cart on my return to the fort, but when the carts arrived

it had carelessly been lost. This I regretted very

much, as Mr. Audubon wanted it. It was nearly sunset

when Bonaventure discovered a Buffalo bull, so we

concluded to encamp for the night, and run the Buffaloes

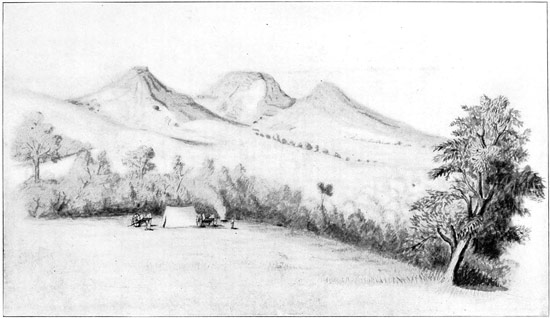

in the morning. We accordingly selected a spot near a

pond of water, which in spring and fall is quite a large

lake, and near which there was abundance of good pasture;

our horses were soon unsaddled and hoppled, a good fire

blazing, and some of the Antelope meat roasting on sticks

before it. As soon as a bit was done, we commenced

operations, and it was soon gone 'the way of all flesh.'

I never before ate meat without salt or pepper, and until

then never fully appreciated these two luxuries, as they

now seemed, nor can any one, until deprived of them, and

seated on a prairie as we were, or in some similar situation.

On the opposite side of the lake we saw a Grizzly Bear,

but he was unapproachable. After smoking our pipes we

rolled ourselves in our robes, with our saddles for pillows,

and were soon lost in a sound, sweet sleep. During the

night I was awakened by a crunching sound; the fire had

died down, and I sat up and looking about perceived a

Wolf quietly feeding on the remains of our supper. One

of the men awoke at the same time and fired at the Wolf,

but without effect, and the fellow fled; we neither saw nor

heard more of him during the night. By daylight we were

all up, and as our horses had not wandered far, it was the

work of a few minutes to catch and saddle them. We rode

three or four miles before we discovered anything, but at

last saw a group of three Buffaloes some miles from us.

We pushed on, and soon neared them; before arriving at

their feeding-ground, we saw, scattered about, immense

quantities of pumice-stone, in detached pieces of all sizes;

several of the hills appeared to be composed wholly of it.

As we approached within two hundred yards of the Buffaloes

they started, and away went the hunters after them.

My first intention of being merely a looker-on continued

up to this moment, but it was impossible to resist following;

almost unconsciously I commenced urging my horse

after them, and was soon rushing up hills and through

ravines; but my horse gave out, and disappointment and

anger followed, as McKenzie and Bonaventure succeeded

in killing two, and wounding a third, which escaped. As

soon as they had finished them, they commenced skinning

and cutting up one, which was soon in the cart, the

offal and useless meat being left on the ground. Again

the Wolves made their appearance as we were leaving;

they seemed shy, but Owen McKenzie succeeded in killing

one, which was old and useless. The other Buffalo was

soon skinned and in the cart. In the meantime McKenzie

and I started on horseback for water. The man who had

charge of the keg had let it all run out, and most fortunately

none of us had wanted water until now. We rode

to a pond, the water of which was very salt and warm, but

we had to drink this or none; we did so, filled our flasks

for the rest of the party, and a few minutes afterward

rejoined them. We started again for more meat to complete

our load. I observed, as we approached the Buffaloes,

that they stood gazing at us with their heads erect,

lashing their sides with their tails; as soon as they discovered

what we were at, with the quickness of thought

they wheeled, and with the most surprising speed, for an

animal apparently so clumsy and awkward, flew before us.

I could hardly imagine that these enormous animals could

move so quickly, or realize that their speed was as great

as it proved to be; and I doubt if in this country one

horse in ten can be found that will keep up with them.

We rode five or six miles before we discovered any more.

At last we saw a single bull, and while approaching him

we started two others; slowly we wended our way towards

them until within a hundred yards, when away they went.

I had now begun to enter into the spirit of the chase, and

off I started, full speed, down a rough hill in swift pursuit;

at the bottom of the hill was a ditch about eight feet wide;

the horse cleared this safely. I continued, leading the

others by some distance, and rapidly approaching the

Buffaloes. At this prospect of success my feelings can

better be imagined than described. I kept the lead of the

others till within thirty or forty yards of the Buffaloes,

when I began making preparations to fire as soon as I was

sufficiently near; imagine, if possible, my disappointment

when I discovered that now, when all my hopes of success

were raised to the highest pitch, I was fated to meet a

reverse as mortifying as success would have been gratifying.

My horse failed, and slackened his pace, despite

every effort of mine to urge him on; the other hunters

rushed by me at full speed, and my horse stopped altogether.

I saw the others fire; the animal swerved a little,

but still kept on. After breathing my horse a while, I

succeeded in starting him up again, followed after them,

and came up in time to fire one shot ere the animal was

brought down. I think that I never saw an eye so ferocious

in expression as that of the wounded Buffalo; rolling

wildly in its socket, inflamed as the eye was, it had the

most frightful appearance that can be imagined; and in

fact, the picture presented by the Buffalo as a whole is

quite beyond my powers of description. The fierce eyes,

blood streaming from his sides, mouth, and nostrils, he was

the wildest, most unearthly-looking thing it ever fell to my

lot to gaze upon. His sufferings were short; he was soon

cut up and placed in the cart, and we retraced our steps

homeward. Whilst proceeding towards our camping-ground

for the night, two Antelopes were killed, and placed

on our carts. Whenever we approached these animals

they were very curious to see what we were; they would

run, first to the right, and then to the left, then suddenly

run straight towards us until within gun-shot, or nearly

so. The horse attracted their attention more than the

rider, and if a slight elevation or bush was between us, they

were easily killed. As soon as their curiosity was gratified

they would turn and run, but it was not difficult to shoot

before this occurred. When they turned they would fly

over the prairie for about a mile, when they would again

stop and look at us. During the day we suffered very

much for want of water, and drank anything that had the

appearance of it, and most of the water, in fact all of it,

was either impregnated with salt, sulphur, or magnesia — most

disgusting stuff at any other time, but drinkable now.

The worst of all was some rain-water that we were obliged

to drink, first placing our handkerchiefs over the cup to

strain it, and keep the worms out of our mouths. I drank

it, and right glad was I to get even this. We rode about

five miles to where we encamped for the night, near a little

pond of water. In a few minutes we had a good fire of

Buffalo dung to drive away mosquitoes that were in clouds

about us. The water had taken away our appetites completely,

and we went to bed without eating any supper.

Our horses and beds were arranged as on the previous

evening. McKenzie and I intended starting for the fort

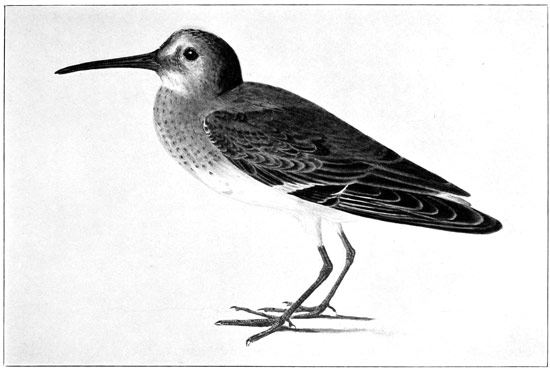

early in the morning. We saw a great many Magpies, Curlews,

Plovers, Doves, and numbers of Antelopes. About

daylight I awoke and roused McKenzie; a man had gone

for the horses, but after a search of two hours returned

without finding them; all the party now went off except

one man and myself, and all returned without success

except Bonaventure, who found an old horse that had been

lost since April last. He was despatched on this to the

fort to get other horses, as we had concluded that ours

were either lost or stolen. As soon as he had gone, one

of the men started again in search of the runaways, and in

a short time returned with them. McKenzie and I soon

rode off. We saw two Grizzly Bears at the lake again.

Our homeward road we made much shorter by cutting off

several turns; we overtook Bonaventure about four miles

from our encampment, and passed him. We rode forty

miles to the fort in a trifle over six hours. We had travelled

in all about one hundred and twenty miles. Bonaventure

arrived two hours after we did, and the carts came

in the evening."

July 8, Saturday. Mr. Culbertson told me this morning

that last spring early, during a snow-storm, he and

Mr. Larpenteur were out in an Indian lodge close by the

fort, when they heard the mares which had young colts

making much noise; and that on going out they saw a

single Wolf that had thrown down one of the colts, and

was about doing the same with another. They both made

towards the spot with their pistols; and, fearing that the

Wolf might kill both the colts, fired before reaching the

spot, when too far off to take aim. Master Wolf ran off,

but both colts bear evidence of his teeth to this day.

When I came down this morning early, I was delighted

to see the dirty and rascally Indians walking off to their

lodge on the other side of the hills, and before many

days they will be at their camp enjoying their merriment

(rough and senseless as it seems to me), yelling out their

scalp song, and dancing. Now this dance, to commemorate

the death of an enemy, is a mere bending and slackening

of the body, and patting of the ground with both

feet at once, in very tolerable time with their music.

Our squaws yesterday joined them in this exemplary ceremony;

one was blackened, and all the others painted with

vermilion. The art of painting in any color is to mix

the color desired with grease of one sort or another; and

when well done, it will stick on for a day or two, if not

longer. Indians are not equal to the whites in the art of

dyeing Porcupine quills; their ingredients are altogether

too simple and natural to equal the knowledge of chemicals.

Mr. Denig dyed a good quantity to-day for Mrs.

Culbertson; he boiled water in a tin kettle with the quills

put in when the water boiled, to remove the oil attached

naturally to them; next they were thoroughly washed, and

fresh water boiled, wherein he placed the color wanted,

and boiled the whole for a few minutes, when he looked

at them to judge of the color, and so continued until all

were dyed. Red, yellow, green, and black quills were

the result of his labors. A good deal of vegetable acid is

necessary for this purpose, as minerals, so they say here,

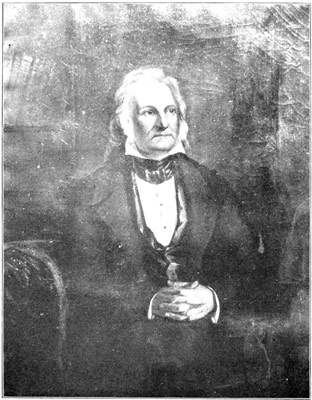

will not answer. I drew at Mr. Culbertson's portrait till

he was tired enough; his wife — a pure Indian — is much

interested in my work. Bell and Sprague, after some

long talk with Harris about geological matters, of which

valuable science he knows a good deal, went off to seek a

Wolf's hole that Sprague had seen some days before, but

of which, with his usual reticence, he had not spoken.

Sprague returned with a specimen of rattle-snake root,

which he has already drawn. Bell saw a Wolf munching

a bone, approached it and shot at it. The Wolf had been

wounded before and ran off slowly, and Bell after it.

Mr. Culbertson and I saw the race; Bell gained on the

Wolf until within thirty steps when he fired again; the

Wolf ran some distance further, and then fell; but Bell

was now exhausted by the heat, which was intense, and

left the animal where it lay without attempting to skin

it. Squires and Provost returned this afternoon about

three o'clock, but the first alone had killed a doe. It

was the first one he had ever shot, and he placed seven

buckshot in her body. Owen went off one way, and

Harris and Bell another, but brought in nothing. Provost

went off to the Opposition camp, and when he returned

told me that a Porcupine was there, and would be

kept until I saw it; so Harris drove me over, at the usual

breakneck pace, and I bought the animal. Mr. Collins is

yet poorly, their hunters have not returned, and they are

destitute of everything, not having even a medicine chest.

We told him to send a man back with us, which he did,

and we sent him some medicine, rice, and two bottles of

claret. The weather has been much cooler and pleasanter

than yesterday.

July 9, Sunday. I drew at a Wolf's head, and Sprague

worked at a view of the fort for Mr. Culbertson. I also

worked on Mr. Culbertson's portrait about an hour. I

then worked at the Porcupine, which is an animal such as

I never saw or Bell either. Its measurements are: from

nose to anterior canthus of the eye, 15⁄8 in., posterior ditto,

21⁄8; conch of ear, 31⁄2; distances from eyes posteriorly, 21⁄4;

fore feet stretched beyond nose, 31⁄2; length of head around,

41⁄8; nose to root of tail, 181⁄2; length of tail vertebr�, 63⁄8;

to end of hair, 73⁄4; hind claws when stretched equal to

end of tail; greatest breadth of palm, 11⁄4; of sole, 13⁄8;

outward width of tail at base, 35⁄8; depth of ditto, 31⁄8;

length of palm, 11⁄2; ditto of sole, 17⁄8; height at shoulder,

11; at rump, 101⁄4; longest hair on the back, 87⁄8; breadth

between ears, 21⁄4; from nostril to split of upper lip, 3⁄4;

upper incisors, 5⁄8; lower ditto, 3⁄4; tongue quite smooth;

weight 11 lbs. The habits of this animal are somewhat

different from those of the Canadian Porcupine. The one

of this country often goes in crevices or holes, and young

McKenzie caught one in a Wolf's den, along with the old

Wolf and seven young; they climb trees, however.

Provost tells me that Wolves are oftentimes destroyed

by wild horses, which he has seen run at the Wolves head

down, and when at a proper distance take them by the

middle of the back with their teeth, and throw them several

feet in the air, after which they stamp upon their

bodies with the fore feet until quite dead. I have a bad

blister on the heel of my right foot, and cannot walk

without considerable pain.

July 10, Monday. Squires, Owen, McKenzie, and Provost,

with a mule, a cart, and Peter the horse, went off at

seven this morning for Antelopes. Bell did not feel well

enough to go with them, and was unable to eat his usual

meal, but I made him some good gruel, and he is better

now. This afternoon Harris went off on horseback after

Rabbits, and he will, I hope, have success. The day has

been fine, and cool compared with others. I took a walk,

and made a drawing of the beautiful sugar-loaf cactus; it

does not open its blossoms until after the middle of the

day, and closes immediately on being placed in the shade.

July 11, Tuesday. Harris returned about ten o'clock last

night, but saw no Hares; how we are to procure any is more

than I can tell. Mr. Culbertson says that it was dangerous

for Harris to go so far as he did alone up the country,

and he must not try it again. The hunters returned this

afternoon, but brought only one buck, which is, however,

beautiful, and the horns in velvet so remarkable that I can

hardly wait for daylight to begin drawing it. I have taken

all the measurements of this perfect animal; it was shot by

old Provost. Mr. Culbertson — whose portrait is nearly

finished — his wife, and I took a ride to look at some grass

for hay, and found it beautiful and plentiful. We saw two

Wolves, a common one and a prairie one. Bell is better.

Sprague has drawn another cactus; Provost and I have

now skinned the buck, and it hangs in the ice-house; the

head, however, is untouched.

July 12, Wednesday. I rose before three, and began

at once to draw the buck's head. Bell assisted me to place

it in the position I wanted, and as he felt somewhat better,

while I drew, he finished the skin of the Porcupine; so that

is saved. Sprague continued his painting of the fort. Just

after dinner a Wolf was seen leisurely walking within one

hundred yards of the fort. Bell took the repeating rifle,

went on the ramparts, fired, and missed it. Mr. Culbertson

sent word to young Owen McKenzie to get a horse and

give it chase. All was ready in a few minutes, and off

went the young fellow after the beast. I left my drawing

long enough to see the pursuit, and was surprised to see

that the Wolf did not start off on a gallop till his pursuer

was within one hundred yards or so of him, and who then

gained rapidly. Suddenly the old sinner turned, and the

horse went past him some little distance. As soon as he

could be turned about McKenzie closed upon him, his gun

flashed twice; but now he was almost � bon touchant, the

gun went off — the Wolf was dead. I walked out to meet

Owen with the beast; it was very poor, very old, and good

for nothing as a specimen. Harris, who had shot at one

last night in the late twilight, had killed it, but was not

aware of it till I found the villain this morning. It had

evidently been dragged at by its brothers, who, however,

had not torn it. Provost went over to the other fort to find

out where the Buffaloes are most abundant, and did not

return till late, so did no hunting. A young dog of this

country's breed ate up all the berries collected by Mrs. Culbertson,

and her lord had it killed for our supper this evening.

The poor thing was stuck with a knife in the throat,

after which it was placed over a hot fire outside of the fort,

singed, and the hair scraped off, as I myself have treated

Raccoons and Opossums. Then the animal was boiled,

and I intend to taste one mouthful of it, for I cannot say

that just now I should relish an entire meal from such

peculiar fare. There are men, however, who much prefer

the flesh to Buffalo meat, or even venison. An ox was

broken to work this day, and worked far better than I

expected. I finished at last Mr. Culbertson's portrait, and

it now hangs in a frame. He and his wife are much pleased

with it, and I am heartily glad they are, for in conscience I

am not; however, it is all I could do, especially with a man

who is never in the same position for one whole minute; so

no more can be expected. The dog was duly cooked and

brought into Mr. Culbertson's room; he served it out to

Squires, Mr. Denig, and myself, and I was astonished when

I tasted it. With great care and some repugnance I put a

very small piece in my mouth; but no sooner had the taste

touched my palate than I changed my dislike to liking, and

found this victim of the canine order most excellent, and

made a good meal, finding it fully equal to any meat I ever

tasted. Old Provost had told me he preferred it to any

meat, and his subsequent actions proved the truth of his

words. We are having some music this evening, and Harris

alone is absent, being at his favorite evening occupation,

namely, shooting at Wolves from the ramparts.

|

|

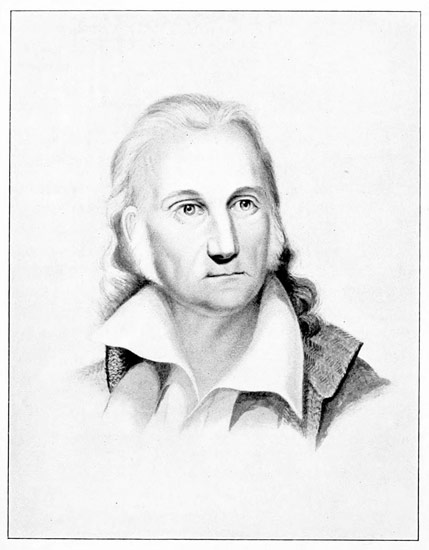

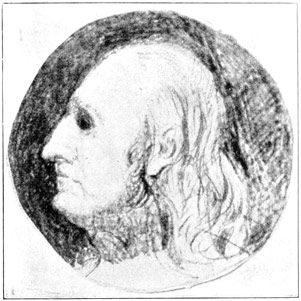

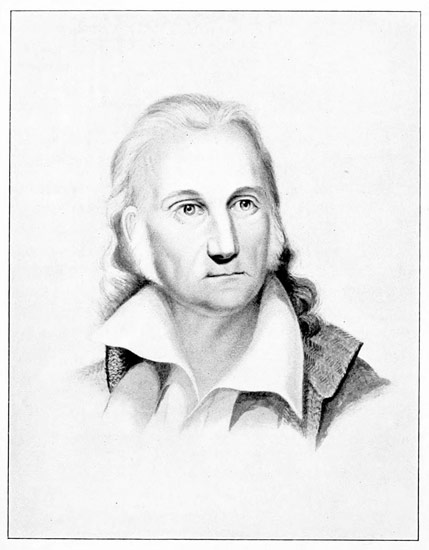

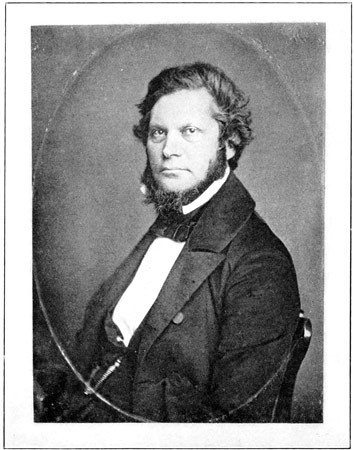

AUDUBON.

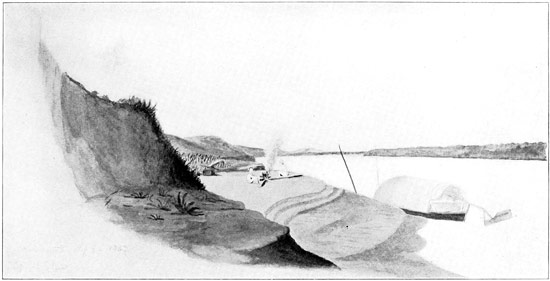

From the pencil sketch by Isaac Sprague, 1842.

In the possession of the Sprague family, Wellesley Hills, Mass.

|

July 13, Thursday. This has been a cloudy and a sultry

day. Sprague finished his drawing and I mine. After

dinner Mr. Culbertson, Squires, and myself went off nine

miles over the prairies to look at the "meadows," as they

are called, where Mr. Culbertson has heretofore cut his

winter crop of hay, but we found it indifferent compared

with that above the fort. We saw Sharp-tailed Grouse, and

what we thought a new species of Lark, which we shot at no

less than ten times before it was killed by Mr. Culbertson, but

not found. I caught one of its young, but it proved to be

only the Shore Lark. Before we reached the meadows we

saw a flock of fifteen or twenty Bob-o-link, Emberiza orizivora,

and on our return shot one of them (a male) on

the wing. It is the first seen since we left St. Louis.

We reached the meadows at last, and tied our nag to a

tree, with the privilege of feeding. Mr. Culbertson and

Squires went in the "meadows," and I walked round the

so-called patch. I shot seven Arkansas Flycatchers on

the wing. After an hour's walking, my companions returned,

but had seen nothing except the fresh tracks of a

Grizzly Bear. I shot at one of the White-rumped Hawks,

of which I have several times spoken, but although it

dropped its quarry and flew very wildly afterwards, it went

out of my sight. We found the beds of Elks and their

fresh dung, but saw none of these animals. I have forgotten

to say that immediately after breakfast this morning I

drove with Squires to Fort Mortimer, and asked Mr. Collins

to let me have his hunter, Boucherville, to go after

Mountain Rams for me, which he promised to do. In the

afternoon he sent a man over to ask for some flour, which

Mr. Culbertson sent him. They are there in the utmost

state of destitution, almost of starvation, awaiting the arrival

of the hunters like so many famished Wolves. Harris

and Bell went across the river and shot a Wolf under the

river bank, and afterwards a Duck, but saw nothing else.

But during their absence we have had a fine opportunity of

witnessing the agility and extreme strength of a year-old

Buffalo bull belonging to the fort. Our cook, who is an

old Spaniard, threw his lasso over the Buffalo's horns, and

all the men in the fort at the time, hauled and pulled the

beast about, trying to get him close to a post. He kicked,

pulled, leaped sideways, and up and down, snorting and

pawing until he broke loose, and ran, as if quite wild, about

the enclosure. He was tied again and again, without any

success, and at last got out of the fort, but was soon retaken,

the rope being thrown round his horns, and he was

brought to the main post of the Buffalo-robe press. There

he was brought to a standstill, at the risk of breaking his

neck, and the last remnant of his winter coat was removed

by main strength, which was the object for which the poor

animal had undergone all this trouble. After Harris

returned to the fort he saw six Sharp-tailed Grouse. At

this season this species have no particular spot where you

may rely upon finding them, and at times they fly through

the woods, and for a great distance, too, where they alight

on trees; when, unless you accidentally see them, you pass

by without their moving. After we passed Fort Mortimer

on our return we saw coming from the banks of the river

no less than eighteen Wolves, which altogether did not

cover a space of more than three or four yards, they

were so crowded. Among them were two Prairie Wolves.

Had we had a good running horse some could have been

shot; but old Peter is long past his running days. The

Wolves had evidently been feeding on some carcass along

the banks, and all moved very slowly. Mr. Culbertson

gave me a grand pair of leather breeches and a very

handsome knife-case, all manufactured by the Blackfeet

Indians.

July 14, Friday. Thermometer 70�-95�. Young

McKenzie went off after Antelopes across the river alone,

but saw only one, which he could not get near. After

breakfast Harris, Squires, and I started after birds of all

sorts, with the wagon, and proceeded about six miles on

the road we had travelled yesterday. We met the hunter

from Fort Mortimer going for Bighorns for me, and Mr.

Culbertson lent him a horse and a mule. We caught two

young of the Shore Lark, killed seven of Sprague's Lark,

but by bad management lost two, either from the wagon,

my hat, or Harris's pockets. The weather was exceedingly

hot. We hunted for Grouse in the wormwood

bushes, and after despairing of finding any, we started up

three from the plain, and they flew not many yards to the

river. We got out of the wagon and pushed for them;

one rose, and Harris shot it, though it flew some yards

before he picked it up. He started another, and just as

he was about to fire, his gunlock caught on his coat, and

off went Mr. Grouse, over and through the woods until out

of sight, and we returned slowly home. We saw ten

Wolves this morning. After dinner we had a curious sight.

Squires put on my Indian dress. McKenzie put on one of

Mr. Culbertson's, Mrs. Culbertson put on her own superb

dress, and the cook's wife put on the one Mrs. Culbertson

had given me. Squires and Owen were painted in an

awful manner by Mrs. Culbertson, the Ladies had their

hair loose, and flying in the breeze, and then all mounted

on horses with Indian saddles and trappings. Mrs. Culbertson

and her maid rode astride like men, and all rode

a furious race, under whip the whole way, for more than

one mile on the prairie; and how amazed would have been

any European lady, or some of our modern belles who

boast their equestrian skill, at seeing the magnificent riding

of this Indian princess — for that is Mrs. Culbertson's rank — and

her servant. Mr. Culbertson rode with them, the

horses running as if wild, with these extraordinary Indian

riders, Mrs. Culbertson's magnificent black hair floating like

a banner behind her. As to the men (for two others had

joined Squires and McKenzie), I cannot compare them to

anything in the whole creation. They ran like wild creatures

of unearthly compound. Hither and thither they

dashed, and when the whole party had crossed the ravine

below, they saw a fine Wolf and gave the whip to their

horses, and though the Wolf cut to right and left Owen

shot at him with an arrow and missed, but Mr. Culbertson

gave it chase, overtook it, his gun flashed, and the Wolf

lay dead. They then ascended the hills and away they

went, with our princess and her faithful attendant in the

van, and by and by the group returned to the camp, running

full speed till they entered the fort, and all this in

the intense heat of this July afternoon. Mrs. Culbertson,

herself a wonderful rider, possessed of both strength and

grace in a marked degree, assured me that Squires was

equal to any man in the country as a rider, and I saw for

myself that he managed his horse as well as any of the

party, and I was pleased to see him in his dress, ornaments,

etc., looking, however, I must confess, after Mrs.

Culbertson's painting his face, like a being from the

infernal regions. Mr. Culbertson presented Harris with a

superb dress of the Blackfoot Indians, and also with a

Buffalo bull's head, for which Harris had in turn presented

him with a gun-barrel of the short kind, and well fitted to

shoot Buffaloes. Harris shot a very young one of Townsend's

Hare, Mr. Denig gave Bell a Mouse, which, although

it resembles Mus leucopus greatly, is much larger, and has

a short, thick, round tail, somewhat blunted.

July 15, Saturday. We were all up pretty early, for

we propose going up the Yellowstone with a wagon,

and the skiff on a cart, should we wish to cross. After

breakfast all of us except Sprague, who did not wish to go,

were ready, and along with two extra men, the wagon, and

the cart, we crossed the Missouri at the fort, and at nine

were fairly under way — Harris, Bell, Mr. Culbertson, and

myself in the wagon, Squires, Provost, and Owen on horseback.

We travelled rather slowly, until we had crossed

the point, and headed the ponds on the prairie that run at

the foot of the hills opposite. We saw one Grouse, but it

could not be started, though Harris searched for it. We

ran the wagon into a rut, but got out unhurt; however, I

decided to walk for a while, and did so for about two

miles, to the turning point of the hills. The wheels of our

vehicle were very shackling, and had to be somewhat

repaired, and though I expected they would fall to pieces, in

some manner or other we proceeded on. We saw several

Antelopes, some on the prairie which we now travelled on,

and many more on the tops of the hills, bounding westward.

We stopped to water the horses at a saline spring,

where I saw that Buffaloes, Antelopes, and other animals

come to allay their thirst, and repose on the grassy margin.

The water was too hot for us to drink, and we awaited the

arrival of the cart, when we all took a good drink of the

river water we had brought with us. After waiting for

nearly an hour to allow the horses to bait and cool themselves,

for it was very warm, we proceeded on, until we

came to another watering-place, a river, in fact, which

during spring overflows its banks, but now has only pools

of water here and there. We soaked our wheels again,

and again drank ourselves. Squires, Provost, and Owen

had left sometime before us, but were not out of our sight,

when we started, and as we had been, and were yet, travelling

a good track, we soon caught up with them. We shot

a common Red-winged Starling, and heard the notes

of what was supposed to be a new bird by my companions,

but which to my ears was nothing more than the

Short-billed Marsh Wren of Nuttall. We reached our

camping-place, say perhaps twenty miles' distance, by four

o'clock, and all things were unloaded, the horses put to

grass, and two or three of the party went in "the point"

above, to shoot something for supper. I was hungry myself,

and taking the Red-wing and the fishing-line, I went to

the river close by, and had the good fortune to catch four fine

catfish, when, my bait giving out, I was obliged to desist,

as I found that these catfish will not take parts of their

own kind as food. Provost had taken a bath, and rowed

the skiff (which we had brought this whole distance on the

cart, dragged by a mule) along with two men, across the

river to seek for game on the point opposite our encampment.

They returned, however, without having shot anything,

and my four catfish were all the fresh provisions that

we had, and ten of us partook of them with biscuit, coffee,

and claret. Dusk coming on, the tent was pitched, and

preparations to rest made. Some chose one spot and

some another, and after a while we were settled. Mr.

Culbertson and I lay together on the outside of the tent,

and all the party were more or less drowsy. About this

time we saw a large black cloud rising in the west; it

was heavy and lowering, and about ten o'clock, when

most of us were pretty nearly sound asleep, the distant

thunder was heard, the wind rose to a gale, and the rain

began falling in torrents. All were on foot in a few

moments, and considerable confusion ensued. Our guns,

all loaded with balls, were hurriedly placed under the tent,

our beds also, and we all crawled in, in the space of a very

few minutes. The wind blew so hard that Harris was

obliged to hold the flappers of the tent with both hands,

and sat in the water a considerable time to do this. Old

Provost alone did not come in, he sat under the shelving

bank of the river, and kept dry. After the gale was over,

he calmly lay down in front of the tent on the saturated

ground, and was soon asleep. During the gale, our fire,

which we had built to keep off the myriads of mosquitoes,

blew in every direction, and we had to watch the embers

to keep them from burning the tent. After all was over,

we snugged ourselves the best way we could in our small

tent and under the wagon, and slept soundly till daylight.

Mr. Culbertson had fixed himself pretty well, but on arising

at daylight to smoke his pipe, Squires immediately

crept into his comfortable corner, and snored there till the

day was well begun. Mr. Culbertson had my knees for a

pillow, and also my hat, I believe, for in the morning,

although the first were not hurt, the latter was sadly out of

shape in all parts. We had nothing for our breakfast

except some vile coffee, and about three quarters of a sea-biscuit,

which was soon settled among us. The men, poor

fellows, had nothing at all. Provost had seen two Deer,

but had had no shot, so of course we were in a quandary,

but it is now —

July 16, Sunday. The weather pleasant with a fine

breeze from the westward, and all eyes were bent upon

the hills and prairie, which is here of great breadth, to spy

if possible some object that might be killed and eaten.

Presently a Wolf was seen, and Owen went after it, and it

was not until he had disappeared below the first low range

of hills, and Owen also, that the latter came within shot of

the rascal, which dodged in all sorts of manners; but Owen

would not give up, and after shooting more than once, he

killed the beast. A man had followed him to help bring

in the Wolf, and when near the river he saw a Buffalo,

about two miles off, grazing peaceably, as he perhaps

thought, safe in his own dominions; but, alas! white

hunters had fixed their eyes upon him, and from that

moment his doom was pronounced. Mr. Culbertson

threw down his hat, bound his head with a handkerchief,

his saddle was on his mare, he was mounted and off and

away at a swift gallop, more quickly than I can describe,

not towards the Buffalo, but towards the place where

Owen had killed the Wolf. The man brought the Wolf

on old Peter, and Owen, who was returning to the camp,

heard the signal gun fired by Mr. Culbertson, and at once

altered his course; his mare was evidently a little heated

and blown by the Wolf chase, but both hunters went after

the Buffalo, slowly at first, to rest Owen's steed, but soon,

when getting within running distance, they gave whip,

overhauled the Bison, and shot at it twice with balls; this

halted the animal; the hunters had no more balls, and

now loaded with pebbles, with which the poor beast was

finally killed. The wagon had been sent from the camp.

Harris, Bell, and Squires mounted on horseback, and travelled

to the scene of action. They met Mr. Culbertson

returning to camp, and he told Bell the Buffalo was a

superb one, and had better be skinned. A man was sent

to assist in the skinning who had been preparing the Wolf

which was now cooking, as we had expected to dine upon

its flesh; but when Mr. Culbertson returned, covered with

blood and looking like a wild Indian, it was decided to

throw it away; so I cut out the liver, and old Provost and

I went fishing and caught eighteen catfish. I hooked

two tortoises, but put them back in the river. I took a

good swim, which refreshed me much, and I came to

dinner with a fine appetite. This meal consisted wholly

of fish, and we were all fairly satisfied. Before long the

flesh of the Buffalo reached the camp, as well as the hide.

The animal was very fat, and we have meat for some days.

It was now decided that Squires, Provost, and Basil (one

of the men) should proceed down the river to the Charbonneau,

and there try their luck at Otters and Beavers, and

the rest of us, with the cart, would make our way back to

the fort. All was arranged, and at half-past three this

afternoon we were travelling towards Fort Union. But

hours previous to this, and before our scanty dinner, Owen

had seen another bull, and Harris and Bell joined us in

the hunt. The bull was shot at by McKenzie, who stopped

its career, but as friend Harris pursued it with two of the

hunters and finished it I was about to return, and thought

sport over for the day. However, at this stage of the proceedings

Owen discovered another bull making his way

slowly over the prairie towards us. I was the only one

who had balls, and would gladly have claimed the privilege

of running him, but fearing I might make out badly on my

slower steed, and so lose meat which we really needed, I

handed my gun and balls to Owen McKenzie, and Bell

and I went to an eminence to view the chase. Owen approached

the bull, which continued to advance, and was

now less than a quarter of a mile distant; either it did not

see, or did not heed him, and they came directly towards

each other, until they were about seventy or eighty yards

apart, when the Buffalo started at a good run, and Owen's

mare, which had already had two hard runs this morning,

had great difficulty in preserving her distance. Owen,

perceiving this, breathed her a minute, and then applying

the whip was soon within shooting distance, and fired a

shot which visibly checked the progress of the bull, and

enabled Owen to soon be alongside of him, when the contents

of the second barrel were discharged into the lungs,

passing through the shoulder blade. This brought him

to a stand. Bell and I now started at full speed, and as

soon as we were within speaking distance, called to Owen

not to shoot again. The bull did not appear to be much

exhausted, but he was so stiffened by the shot on the

shoulder that he could not turn quickly, and taking advantage

of this we approached him; as we came near he

worked himself slowly round to face us, and then made a

lunge at us; we then stopped on one side and commenced

discharging our pistols with little or no effect, except to

increase his fury with every shot. His appearance was

now one to inspire terror had we not felt satisfied of our

ability to avoid him. However, even so, I came very near

being overtaken by him. Through my own imprudence,

I placed myself directly in front of him, and as he advanced

I fired at his head, and then ran ahead of him, instead

of veering to one side, not supposing that he was

able to overtake me; but turning my head over my shoulder,

I saw to my horror, Mr. Bull within three feet of me,

prepared to give me a taste of his horns. The next instant

I turned sharply off, and the Buffalo being unable to

turn quickly enough to follow me, Bell took the gun from

Owen and shot him directly behind the shoulder blade.

He tottered for a moment, with an increased jet of blood

from the mouth and nostrils, fell forward on his horns,

then rolled over on his side, and was dead. He was a

very old animal, in poor case, and only part of him was

worth taking to the fort. Provost, Squires, and Basil

were left at the camp preparing for their departure after

Otter and Beaver as decided. We left them eight or nine

catfish and a quantity of meat, of which they took care to

secure the best, namely the boss or hump. On our homeward

way we saw several Antelopes, some quite in the

prairie, others far away on the hills, but all of them on

the alert. Owen tried unsuccessfully to approach several

of them at different times. At one place where two were

seen he dismounted, and went round a small hill (for these

animals when startled or suddenly alarmed always make

to these places), and we hoped would have had a shot; but

alas! no! One of the Antelopes ran off to the top of another

hill, and the other stood looking at him, and us perhaps,

till Owen (who had been re-mounted) galloped off

towards us. My surprise was great when I saw the other

Antelope following him at a good pace (but not by bounds

or leaps, as I had been told by a former traveller they

sometimes did), until it either smelt him, or found out he

was no friend, and turning round galloped speedily off to

join the one on the lookout. We saw seven or eight

Grouse, and Bell killed one on the ground. We saw a

Sand-hill Crane about two years old, looking quite majestic

in a grassy bottom, but it flew away before we were

near enough to get a shot. We passed a fine pond or

small lake, but no bird was there. We saw several parcels

of Ducks in sundry places, all of which no doubt had

young near. When we turned the corner of the great

prairie we found Owen's mare close by us. She had run

away while he was after Antelopes. We tied her to a log

to be ready for him when he should reach the spot. He

had to walk about three miles before he did this. However,

to one as young and alert as Owen, such things are

nothing. Once they were not to me. We saw more Antelope

at a distance, here called "Cabris," and after a

while we reached the wood near the river, and finding

abundance of service-berries, we all got out to break

branches of these plants, Mr. Culbertson alone remaining

in the wagon; he pushed on for the landing. We walked

after him munching our berries, which we found very good,

and reached the landing as the sun was going down behind

the hills. Young McKenzie was already there, having cut

across the point. We decided on crossing the river ourselves,

and leaving all behind us except our guns. We took

to the ferry-boat, cordelled it up the river for a while, then

took to the nearest sand-bar, and leaping into the mud

and water, hauled the heavy boat, Bell and Harris steering

and poling the while. I had pulled off my shoes and

socks, and when we reached the shore walked up to the

fort barefooted, and made my feet quite sore again; but

we have had a rest and a good supper, and I am writing

in Mr. Culbertson's room, thinking over all God's blessings

on this delightful day.

July 17, Monday. A beautiful day, with a west wind.

Sprague, who is very industrious at all times, drew some

flowers, and I have been busy both writing and drawing.

In the afternoon Bell went after Rabbits, but saw one

only, which he could not get, and Sprague walked to the

hills about two miles off, but could not see any portion

of the Yellowstone River, which Mr. Catlin has given in

his view, as if he had been in a balloon some thousands

of feet above the earth. Two men arrived last evening

by land from Fort Pierre, and brought a letter, but no

news of any importance; one is a cook as well as a hunter,

the other named Wolff, a German, and a tinsmith by

trade, though now a trapper.

July 18, Tuesday. When I went to bed last night the

mosquitoes were so numerous downstairs that I took my

bed under my arm and went to a room above, where I

slept well. On going down this morning, I found two

other persons from Fort Pierre, and Mr. Culbertson very

busy reading and writing letters. Immediately after

breakfast young McKenzie and another man were despatched

on mules, with a letter for Mr. Kipp, and Owen

expects to overtake the boat in three or four days. An

Indian arrived with a stolen squaw, both Assiniboins;

and I am told such things are of frequent occurrence

among these sons of nature. Mr. Culbertson proposed

that we should take a ride to see the mowers, and Harris

and I joined him. We found the men at work, among

them one called Bernard Adams, of Charleston, S.C.,

who knew the Bachmans quite well, and who had read

the whole of the "Biographies of Birds." Leaving the

men, we entered a ravine in search of plants, etc., and

having started an Owl, which I took for the barred one, I

left my horse and went in search of it, but could not

see it, and hearing a new note soon saw a bird not to be

mistaken, and killed it, when it proved, as I expected, to

be the Rock Wren; then I shot another sitting by the

mouth of a hole. The bird did not fly off; Mr. Culbertson

watched it closely, but when the hole was demolished

no bird was to be found. Harris saw a Shrike, but of

what species he could not tell, and he also found some

Rock Wrens in another ravine. We returned to the fort

and promised to visit the place this afternoon, which we

have done, and procured three more Wrens, and killed the

Owl, which proves to be precisely the resemblance of the

Northern specimen of the Great Horned Owl, which we

published under another name. The Rock Wren, which

might as well be called the Ground Wren, builds its nest

in holes, and now the young are well able to fly, and we

procured one in the act. In two instances we saw these

birds enter a hole here, and an investigation showed a

passage or communication, and on my pointing out a hole

to Bell where one had entered, he pushed his arm in and

touched the little fellow, but it escaped by running up

his arm and away it flew. Black clouds now arose in the

west, and we moved homewards. Harris and Bell went

to the mowers to get a drink of water, and we reached

home without getting wet, though it rained violently for

some time, and the weather is much cooler. Not a word

yet from Provost and Squires.

July 19, Wednesday. Squires and Provost returned

early this morning, and again I give the former my journal

that I may have the account of the hunt in his own

words. "As Mr. Audubon has said, he left Provost,

Basil, and myself making ready for our voyage down the

Yellowstone. The party for the fort were far in the

blue distance ere we bid adieu to our camping-ground.

We had wished the return party a pleasant ride and safe

arrival at the fort as they left us, looking forward to a

good supper, and what I now call a comfortable bed. We

seated ourselves around some boiled Buffalo hump, which,

as has been before said, we took good care to appropriate

to ourselves according to the established rule of this

country, which is, 'When you can, take the best,' and we

had done so in this case, more to our satisfaction than to

that of the hunters. Our meal finished, we packed everything

we had in the skiff, and were soon on our way

down the Yellowstone, happy as could be; Provost acting

pilot, Basil oarsman, and your humble servant seated

on a Buffalo robe, quietly smoking, and looking on the

things around. We found the general appearance of the

Yellowstone much like the Missouri, but with a stronger

current, and the water more muddy. After a voyage of

two hours Charbonneau River made its appearance, issuing

from a clump of willows; the mouth of this river we

found to be about ten feet wide, and so shallow that we

were obliged to push our boat over the slippery mud for

about forty feet. This passed, we entered a pond formed

by the contraction of the mouth and the collection of mud

and sticks thereabouts, the pond so formed being six or

eight feet deep, and about fifty feet wide, extending about

a mile up the river, which is very crooked indeed. For

about half a mile from the Yellowstone the shore is

lined with willows, beyond which is a level prairie, and

on the shores of the stream just beyond the willows are

a few scattered trees. About a quarter of a mile from the

mouth of the river, we discovered what we were in search

of, the Beaver lodge. To measure it was impossible, as

it was not perfect, in the first place, in the next it was so

muddy that we could not get ashore, but as well as I can

I will describe it. The lodge is what is called the summer

lodge; it was comprised wholly of brush, willow

chiefly, with a single hole for the entrance and exit of the

Beaver. The pile resembled, as much as anything to

which I can compare it, a brush heap about six feet high,

and about ten or fifteen feet base, and standing seven or

eight feet from the water. There were a few Beaver

tracks about, which gave us some encouragement. We

proceeded to our camping-ground on the edge of the

prairie; here we landed all our baggage; while Basil

made a fire, Provost and I started to set our traps — the

two extremes of hunters, the skilful old one, and the

ignorant pupil; but I was soon initiated in the art of

setting Beaver traps, and to the uninitiated let me say,

'First, find your game, then catch it,' if you can. The

first we did, the latter we tried to do. We proceeded to

the place where the greatest number of tracks were seen,

and commenced operations. At the place where the path

enters the water, and about four inches beneath the surface,

a level place is made in the mud, upon which the

trap is placed, the chain is then fastened to a stake which

is firmly driven in the ground under water. The end of

a willow twig is then chewed and dipped in the 'Medicine

Horn,' which contains the bait; this consists of

castoreum mixed with spices; a quantity is collected on

the chewed end of the twig, the stick is then placed or

stuck in the mud on the edge of the water, leaving the

part with the bait about two inches above the surface and

in front of the trap; on each side the bait and about six

inches from it, two dried twigs are placed in the ground;

this done, all's done, and we are ready for the visit of

Monsieur Castor. We set two traps, and returned to our

camp, where we had supper, then pitched our tent and

soon were sound asleep, but before we were asleep we

heard a Beaver dive, and slap his tail, which sounded like

the falling of a round stone in the water; here was encouragement

again. In the morning (Monday) we examined

our traps and found — nothing. We did not therefore

disturb the traps, but examined farther up the river, where

we discovered other tracks and resolved to set our traps

there, as Provost concluded that there was but one Beaver,

and that a male. We returned to camp and made a good

breakfast on Buffalo meat and coffee, sans salt, sans pepper,

sans sugar, sans anything else of any kind. After

breakfast Provost shot a doe. In the afternoon we removed

one trap, Basil and I gathered some wild-gooseberries

which I stewed for supper, and made a sauce,

which, though rather acid, was very good with our meat.

The next morning, after again examining our traps and

finding nothing, we decided to raise camp, which was

accordingly done; everything was packed in the skiff, and

we proceeded to the mouth of the river. The water had

fallen so much since we had entered, as to oblige us to

strip, jump in the mud, and haul the skiff over; rich and

rare was the job; the mud was about half thigh deep, and

a kind of greasy, sticky, black stuff, with a something

about it so very peculiar as to be rather unpleasant; however,

we did not mind much, and at last got into the Yellowstone,

scraped and washed the mud off, and encamped

on a prairie about one hundred yards below the Charbonneau.

It was near sunset; Provost commenced fishing;

we joined him, and in half an hour we caught sixteen catfish,

quite large ones. During the day Provost started to

the Mauvaises Terres to hunt Bighorns, but returned unsuccessful.

He baited his traps for the last time. During

his absence thunder clouds were observed rising all

around us; we stretched our tent, removed everything inside

it, ate our supper of meat and coffee, and then went

to bed. It rained some part of the night, but not enough

to wet through the tent. The next morning (Tuesday) at

daylight, Provost started to examine his traps, while we

at the camp put everything in the boat, and sat down to

await his return, when we proceeded on our voyage down

the Yellowstone to Fort Mortimer, and from thence by

land to Fort Union. Nothing of any interest occurred

except that we saw two does, one young and one buck of

the Bighorns; I fired at the buck which was on a high

cliff about a hundred and fifty yards from us; I fired

above it to allow for the falling of the ball, but the gun

shot so well as to carry where I aimed. The animal was

a very large buck; Provost says one of the largest he had

seen. As soon as I fired he started and ran along the

side of the hill which looked almost perpendicular, and I

was much astonished, not only at the feat, but at the surprising

quickness with which he moved along, with no

apparent foothold. We reached Fort Mortimer about

seven o'clock; I left Basil and Provost with the skiff, and

I started for Fort Union on foot to send a cart for them.

On my way I met Mr. Audubon about to pay a visit to

Fort Mortimer; I found all well, despatched the cart,

changed my clothes, and feel none the worse for my five

days' camping, and quite ready for a dance I hear we are

to have to-night."

This morning as I walked to Fort Mortimer, meeting

Squires as he has said, well and happy as a Lark, I was

surprised to see a good number of horses saddled, and

packed in different ways, and I hastened on to find what

might be the matter. When I entered the miserable

house in which Mr. Collins sleeps and spends his time

when not occupied out of doors, he told me thirteen men

and seven squaws were about to start for the lakes, thirty-five

miles off, to kill Buffaloes and dry their meat, as the

last his hunters brought in was already putrid. I saw

the cavalcade depart in an E.N.E. direction, remained a

while, and then walked back. Mr. Collins promised me

half a dozen balls from young animals. Provost was discomfited

and crestfallen at the failure of the Beaver hunt;

he brought half a doe and about a dozen fine catfish.

Mr. Culbertson and I are going to see the mowers, and

to-morrow we start on a grand Buffalo hunt, and hope for

Antelopes, Wolves, and Foxes.

July 20, Thursday. We were up early, and had our

breakfast shortly after four o'clock, and before eight had

left the landing of the fort, and were fairly under way for

the prairies. Our equipment was much the same as before,

except that we had two carts this time. Mr. C.

drove Harris, Bell, and myself, and the others rode on the

carts and led the hunting horses, or runners, as they are

called here. I observed a Rabbit running across the road,

and saw some flowers different from any I had ever seen.

After we had crossed a bottom prairie, we ascended between

the high and rough ravines until we were on the

rolling grounds of the plains. The fort showed well from

this point, and we also saw a good number of Antelopes,

and some young ones. These small things run even faster

than the old ones. As we neared the Fox River some one

espied four Buffaloes, and Mr. C., taking the telescope,

showed them to me, lying on the ground. Our heads and

carts were soon turned towards them, and we travelled

within half a mile of them, concealed by a ridge or hill

which separated them from us. The wind was favorable,

and we moved on slowly round the hill, the hunters being

now mounted. Harris and Bell had their hats on, but

Owen and Mr. Culbertson had their heads bound with

handkerchiefs. With the rest of the party I crawled on

the ridge, and saw the bulls running away, but in a direction

favorable for us to see the chase. On the word of

command the horses were let loose, and away went the

hunters, who soon were seen to gain on the game; two

bulls ran together and Mr. C. and Bell followed after

them, and presently one after another of the hunters followed

them. Mr. C. shot first, and his bull stopped at

the fire, walked towards where I was, and halted about

sixty yards from me. His nose was within a few inches

of the ground; the blood poured from his mouth, nose, and

side, his tail hung down, but his legs looked as firm as

ever, but in less than two minutes the poor beast fell on

his side, and lay quite dead. Bell and Mr. Culbertson

went after the second. Harris took the third, and Squires

the fourth. Bell's shot took effect in the buttock, and

Mr. Culbertson shot, placing his ball a few inches above

or below Bell's; after this Mr. Culbertson ran no more.

At this moment Squires's horse threw him over his

head, fully ten feet; he fell on his powder-horn and

was severely bruised; he cried to Harris to catch his

horse, and was on his legs at once, but felt sick for a few

minutes. Harris, who was as cool as a cucumber, neared

his bull, shot it through the lungs, and it fell dead on the

spot. Bell was now seen in full pursuit of his game, and

Harris joined Squires, and followed the fourth, which,

however, was soon out of my sight. I saw Bell shooting

two or three times, and I heard the firing of Squires and

perhaps Harris, but the weather was hot, and being afraid

of injuring their horses, they let the fourth bull make his

escape. Bell's bull fell on his knees, got up again, and

rushed on Bell, and was shot again. The animal stood a

minute with his tail partially elevated, and then fell dead;

through some mishap Bell had no knife with him, so did

not bring the tongue, as is customary. Mr. Culbertson

walked towards the first bull and I joined him. It was a

fine animal about seven years old; Harris's and Bell's

were younger. The first was fat, and was soon skinned

and cut up for meat. Mr. Culbertson insisted on calling

it my bull, so I cut off the brush of the tail and placed it

in my hat-band. We then walked towards Harris, who

was seated on his bull, and the same ceremony took place,

and while they were cutting the animal up for meat, Bell,

who said he thought his bull was about three quarters of

a mile distant, went off with me to see it; we walked at

least a mile and a half, and at last came to it. It was a

poor one, and the tongue and tail were all we took away,

and we rejoined the party, who had already started the

cart with Mr. Pike, who was told to fall to the rear, and

reach the fort before sundown; this he could do readily,

as we were not more than six miles distant. Mr. Culbertson

broke open the head of "my" bull, and ate part of

the brains raw, and yet warm, and so did many of the

others, even Squires. The very sight of this turned my

stomach, but I am told that were I to hunt Buffalo one

year, I should like it "even better than dog meat." Mr.

Pike did not reach the fort till the next morning about

ten, I will say en passant. We continued our route, passing

over the same road on which we had come, and about

midway between the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers.

We saw more Antelopes, but not one Wolf; these rascals

are never abundant where game is scarce, but where game

is, there too are the Wolves. When we had travelled

about ten miles further we saw seven Buffaloes grazing

on a hill, but as the sun was about one hour high, we

drove to one side of the road where there was a pond of

water, and there stopped for the night; while the hunters

were soon mounted, and with Squires they went off, leaving

the men to arrange the camp. I crossed the pond,

and having ascended the opposite bank, saw the bulls

grazing as leisurely as usual. The hunters near them,

they started down the hill, and the chase immediately began.

One broke from the rest and was followed by Mr.

C. who shot it, and then abandoned the hunt, his horse

being much fatigued. I now counted ten shots, but all

was out of my sight, and I seated myself near a Fox hole,

longing for him. The hunters returned in time; Bell

and Harris had killed one, but Squires had no luck,

owing to his being unable to continue the chase on account

of the injury he had received from his fall. We

had a good supper, having brought abundance of eatables

and drinkables. The tent was pitched; I put up my mosquito-bar

under the wagon, and there slept very soundly

till sunrise. Harris and Bell wedged together under another

bar, Mr. C. went into the tent, and Squires, who is

tough and likes to rough it with the hunters, slept on a

Buffalo hide somewhere with Moncr�vier, one of the most

skilful of the hunters. The horses were all hoppled and

turned to grass; they, however, went off too far, and had

to be sent after, but I heard nothing of all this. As

there is no wood on the prairies proper, our fire was made

of Buffalo dung, which is so abundant that one meets

these deposits at every few feet and in all directions.

July 21, Friday. We were up at sunrise, and had our

coffee, after which Lafleur a mulatto, Harris, and Bell

went off after Antelopes, for we cared no more about

bulls; where the cows are, we cannot tell. Cows run

faster than bulls, yearlings faster than cows, and calves

faster than any of these. Squires felt sore, and his side

was very black, so we took our guns and went after Black-breasted

Lark Buntings, of which we saw many, but could

not near them. I found a nest of them, however, with

five eggs. The nest is planted in the ground, deep enough

to sink the edges of it. It is formed of dried fine grasses

and roots, without any lining of hair or wool. By and by

we saw Harris sitting on a high hill about one mile off,

and joined him; he said the bulls they had killed last

evening were close by, and I offered to go and see the

bones, for I expected that the Wolves had devoured it

during the night. We travelled on, and Squires returned

to the camp. After about two miles of walking against a

delightful strong breeze, we reached the animals; Ravens

or Buzzards had worked at the eyes, but only one Wolf,

apparently, had been there. They were bloated, and

smelt quite unpleasant. We returned to the camp and

saw a Wolf cross our path, and an Antelope looking at

us. We determined to stop and try to bring him to us; I

lay on my back and threw my legs up, kicking first one

and then the other foot, and sure enough the Antelope

walked towards us, slowly and carefully, however. In

about twenty minutes he had come two or three hundred

yards; he was a superb male, and I looked at him for

some minutes; when about sixty yards off I could see his

eyes, and being loaded with buck-shot pulled the trigger

without rising from my awkward position. Off he went;

Harris fired, but he only ran the faster for some hundred

yards, when he turned, looked at us again, and was off.

When we reached camp we found Bell there; he had shot

three times at Antelopes without killing; Lafleur had

also returned, and had broken the foreleg of one, but an

Antelope can run fast enough with three legs, and he saw

no more of it. We now broke camp, arranged the horses

and turned our heads towards the Missouri, and in four

and three-quarter hours reached the landing. On entering

the wood we again broke branches of service-berries,

and carried a great quantity over the river. I much enjoyed

the trip; we had our supper, and soon to bed in our

hot room, where Sprague says the thermometer has been

at 99� most of the day. I noticed it was warm when walking.

I must not forget to notice some things which happened

on our return. First, as we came near Fox River,

we thought of the horns of our bulls, and Mr. Culbertson,

who knows the country like a book, drove us first to

Bell's, who knocked the horns off, then to Harris's, which

was served in the same manner; this bull had been eaten

entirely except the head, and a good portion of mine had

been devoured also; it lay immediately under "Audubon's

Bluff" (the name Mr. Culbertson gave the ridge on

which I stood to see the chase), and we could see it when

nearly a mile distant. Bell's horns were the handsomest

and largest, mine next best, and Harris's the smallest,

but we are all contented. Mr. Culbertson tells me that

Harris and Bell have done wonders, for persons who have

never shot at Buffaloes from on horseback. Harris had a

fall too, during his second chase, and was bruised in the

manner of Squires, but not so badly. I have but little

doubt that Squires killed his bull, as he says he shot it

three times, and Mr. Culbertson's must have died also.

What a terrible destruction of life, as it were for nothing,

or next to it, as the tongues only were brought in,

and the flesh of these fine animals was left to beasts and

birds of prey, or to rot on the spots where they fell. The

prairies are literally covered with the skulls of the victims,

and the roads the Buffalo make in crossing the

prairies have all the appearance of heavy wagon tracks.

We saw young Golden Eagles, Ravens, and Buzzards. I

found the Short-billed Marsh Wren quite abundant, and

in such localities as it is found eastward. The Black-breasted

Prairie-bunting flies much like a Lark, hovering

while singing, and sweeping round and round, over

and above its female while she sits on the eggs on the

prairie below. I saw only one Gadwall Duck; these

birds are found in abundance on the plains where

water and rushes are to be found. Alas! alas! eighteen

Assiniboins have reached the fort this evening in two

groups; they are better-looking than those previously

seen by us.

July 22, Saturday. Thermometer 99�-102�. This day

has been the hottest of the season, and we all felt the influence

of this densely oppressive atmosphere, not a breath

of air stirring. Immediately after breakfast Provost and

Lafleur went across the river in search of Antelopes, and

we remained looking at the Indians, all Assiniboins, and

very dirty. When and where Mr. Catlin saw these Indians

as he has represented them, dressed in magnificent

attire, with all sorts of extravagant accoutrements, is more

than I can divine, or Mr. Culbertson tell me. The evening

was so hot and sultry that Mr. C. and I went into

the river, which is now very low, and remained in the

water over an hour. A dozen catfish were caught in the

main channel, and we have had a good supper from part

of them. Finding the weather so warm I have had my

bed brought out on the gallery below, and so has Squires.

The Indians are, as usual, shut out of the fort, all the

horses, young Buffaloes, etc., shut in; and much refreshed

by my bath, I say God bless you, and good-night.

July 23, Sunday. Thermometer 84�. I had a very

pleasant night, and no mosquitoes, as the breeze rose a

little before I lay down; and I anticipated a heavy thunder

storm, but we had only a few drops of rain. About

one o'clock Harris was called to see one of the Indians,

who was bleeding at the nose profusely, and I too went

to see the poor devil. He had bled quite enough, and

Harris stopped his nostrils with cotton, put cold water on

his neck and head — God knows when they had felt it

before — and the bleeding stopped. These dirty fellows

had made a large fire between the walls of the fort, but

outside the inner gates, and it was a wonder that the

whole establishment was not destroyed by fire. Before

sunrise they were pounding at the gate to be allowed to

enter, but, of course, this was not permitted. When the

sun had fairly risen, some one came and told me the hill-tops

were covered with Indians, probably Blackfeet. I

walked to the back gate, and the number had dwindled,

or the account been greatly exaggerated, for there seemed

only fifty or sixty, and when, later, they were counted,

there were found to be exactly seventy. They remained

a long time on the hill, and sent a youth to ask for

whiskey. But whiskey there is none for them, and very

little for any one. By and by they came down the hill

leading four horses, and armed principally with bows and

arrows, spears, tomahawks, and a few guns. They have

proved to be a party of Crees from the British dominions

on the Saskatchewan River, and have been fifteen days in

travelling here. They had seen few Buffaloes, and were

hungry and thirsty enough. They assured Mr. Culbertson

that the Hudson's Bay Company supplied them all with

abundance of spirituous liquors, and as the white traders

on the Missouri had none for them, they would hereafter

travel with the English. Now ought not this subject to

be brought before the press in our country and forwarded

to England? If our Congress will not allow our traders

to sell whiskey or rum to the Indians, why should not the

British follow the same rule? Surely the British, who

are so anxious about the emancipation of the blacks,

might as well take care of the souls and bodies of the

redskins. After a long talk and smoking of pipes, tobacco,

flints, powder, gun-screws and vermilion were

placed before their great chief (who is tattooed and has

a most rascally look), who examined everything minutely,

counting over the packets of vermilion; more tobacco

was added, a file, and a piece of white cotton with which

to adorn his head; then he walked off, followed by his

son, and the whole posse left the fort. They passed by

the garden, pulled up a few squash vines and some turnips,

and tore down a few of the pickets on their way

elsewhere. We all turned to, and picked a quantity of

peas, which with a fine roast pig, made us a capital

dinner. After this, seeing the Assiniboins loitering

about the fort, we had some tobacco put up as a target,

and many arrows were sent to enter the prize, but I never

saw Indians — usually so skilful with their bows — shoot

worse in my life. Presently some one cried there were

Buffaloes on the hill, and going to see we found that four

bulls were on the highest ridge standing still. The

horses being got in the yard, the guns were gathered,

saddles placed, and the riders mounted, Mr. C., Harris,

and Bell; Squires declined going, not having recovered

from his fall, Mr. C. led his followers round the hills by

the ravines, and approached the bulls quite near, when

the affrighted cattle ran down the hills and over the

broken grounds, out of our sight, followed by the hunters.

When I see game chased by Mr. Culbertson, I feel confident

of its being killed, and in less than one hour he

had killed two bulls, Harris and Bell each one. Thus

these poor animals which two hours before were tranquilly

feeding are now dead; short work this. Harris and Bell

remained on the hills to watch the Wolves, and carts

being ordered, Mr. C. and I went off on horseback to the

second one he had killed. We found it entire, and I

began to operate upon it at once; after making what

measurements and investigations I desired, I saved the

head, the tail, and a large piece of the silky skin from

the rump. The meat of three of the bulls was brought

to the fort, the fourth was left to rot on the ground. Mr.

C. cut his finger severely, but paid no attention to that;

I, however, tore a strip off my shirt and bound it up for

him. It is so hot I am going to sleep on the gallery

again; the thermometer this evening is 89�.

July 24, Monday. I had a fine sleep last night, and

this morning early a slight sprinkling of rain somewhat