E. W. Andrews

Without the Wind.

© E. W. Andrews

Email:

ewandrewsnrg@gmail.com.

Used by permission.

All rights reserved.

Table of Contents

- Chapter 1: L’Homme

- Chapter 2: The Furnace

- Chapter 3: Le Reve

- Chapter 4: Shooters

- Chapter 5: The Birdhouse

- Chapter 6: Blades

- Chapter 7: Stakes

- Chapter 8: The Songs

- Chapter 9: Tables

- Chapter 10: The Dead

- Chapter 11: The River

Prologue

Over the course of four years, America ate itself alive in a brutal civil war. By the end of the conflict, the country had become stronger through its resolve but weaker from its wounds. Eight years after the war ended, the country was bogged down in debt and maimed by the high cost of victory, corruption, and the Reconstruction.

It was during this flailing recovery that the United States found itself on the verge of a new war with Spain. On Wednesday, November 5, 1873, the American merchant ship Virginius, carrying weapons and munitions, was seized in Cuban waters by the Spanish navy at war with Cuban separatists. The ship’s captain, John Fry, and four other Americans were executed the following day, sparking outrage in America and a call for retribution.

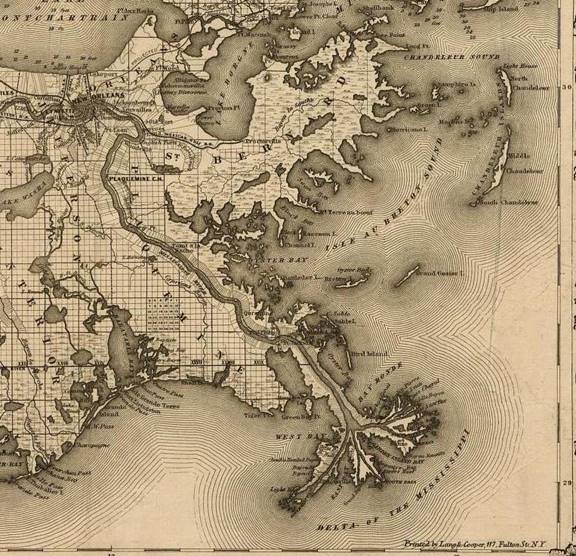

Originally a Confederate blockade runner, the Virginius had been confiscated by the United States in 1865. Five years later, she was purchased by John F. Patterson on behalf of Cubans seeking independence from Spain. Having scrapped its own ironclads following the Civil War, the US Navy now found itself helpless as one of two ironclad warships in the Western Hemisphere sat in New York harbor under a Spanish flag. Despite unofficially supporting the Cuban cause, Secretary of State Hamilton Fish opened diplomatic back channels, seeking to avoid an expensive and potentially embarrassing war with Spain. The other ironclad warship, the newly refurbished CSS Albemarle, rechristened Le Reve, steamed west from Biloxi to the port of New Orleans under control of Cuban sympathizer, salvage merchant, and gunrunner Captain Lucius Cephus. The ship was suspected of carrying the 6.4-inch howitzer Brooke rifle that had gone missing when it was originally sunk, raised, and then ultimately sold for scrap by the Union navy. To avoid being drawn into a war with Spain, Secretary Fish ordered the ship seized and the owner duly compensated to continue unofficial support for the Cuban cause.

This is the story of the pursuit of Le Reve.

Chapter 1: L’Homme

James Phobetor lay face down in the black bayou mud. He’d festered there for hours after he had fallen, rolled over the curb, and slid down past the sidewalk, coming to rest in the gutter. He was a bedraggled, snoring corpse. Overnight, the rain had pissed down on him as it had every night that week. His broad, brown hat was a ragged extension of the canvas slicker he lived in, dragged himself around in, had survived in — and that likely would survive him. All throughout the evening and late into the night, everyone in the town of Pointe à la Hache, on their way to the saloon or the restaurant up the street, had walked past him as he sucked at the mud and sputtered the water of the ditch.

With the red sun now percolating in the east, he remained so entrenched that not a single rivulet of rainwater trembled free of the small pools collecting on the outer surface of his waxed coat. The downpour had stopped an hour before sunrise, and the morning warmth had baked him into the sandy dirt. It was in this cocoon that finally some lucency stirred. He rolled over, and a lonely, beady blue eye opened to the upside-down world before him. He crawled to his knees painfully. Staggering, he dragged himself over to the planks of the sidewalk, and with the assistance of the light post, he reached forward and pulled himself up with a grunt. The front of his dark-gray suit was crusted with sand and mud that crumbled as he straightened up, gathered his feet beneath him, and shoved off. He lumbered up the street, wobbling as the wind changed and lifted the tails of his long coat.

Phobetor stopped to rest against the wall of the post office on the corner. The breeze charged up from behind him. Rising from the river in the west, it climbed the slope of the road up from the dock and rippled through the palm trees lining the street. He struggled to find the tobacco pouch in the pocket of his coat. Eventually locating it, he managed to gather the few remaining crumbled leaves into an impoverished cigarette. Pulling his hat down against the wind, he raised his arm, ducked his head, and ignited the twist of paper he held in his lips. With a sigh of achievement, he heaved a billowy cloud of smoke and stepped away from the post office. The archaic bayou town was quiet. The sandy street was empty. The windows in the plastered white façades of the shops and their corrugated-tin roofs angled a debilitating glare at him, creating tracers in the corners of his eyes as he searched the street. The gray horse was still hitched where he had left it — in front of the red-brick courthouse that dominated the square at the end of the street.

Nauseated, he stumbled down onto the sandy road, clutching his stomach as he made his way over to the courthouse steps, where he mounted the gray horse. Pulling on the reins to turn her head, he jabbed her into a trot as he slumped over the saddle horn, riding south. He never looked up.

Beyond the white, double-galleried hotel at the end of the block, the gray horse and crumpled rider descended the street briskly. As they reached the great, parading iron struts of the bridge, she shied and halted, looking down the brackish creek to the inlet where it emptied into the broad river in the distance. The cessation of motion waking him, Phobetor stroked her neck and whispered to her. Now again, although with a cautious address, she proceeded across the wide planks of the bridge in a series of rattling, muddy clomps that reverberated through the beams. Upon reaching the other side, she turned east without his instruction. They melted into the morass of cypress and hanging moss, retreating from the heat of the sun. Absorbed in the canopy, they disappeared, the gray horse hanging her head low and slowly picking out her steps in the muddy rut along the back side of the riverbank.

Chapter 2: The Furnace

Phobetor’s hand shook as he lifted the iron skillet off the potbellied stove. His grip was weak, his palms sweaty, his skin pale. His other beggarly hand scraped the eggs over with the sheepsfoot blade of his knife. He smelled like the whiskey he was drinking. The liquor sat in the warm, half-empty ceramic jug on the table beside him. It had been nearly six hours since he had broken free of his hole in the mud on the streets of La Hache. His hunger had finally driven him from his rope bed to cook enough eggs and bacon to hold down the vomit still boiling up inside of him.

He shoveled the crackling eggs out of the skillet onto the plate, where the bacon sat dripping in grease. His coat hung from a peg on the door behind him. As the meat glazed dry, he got up and looked at the jacket. As he shook it, sandy clay fell silently from its creases. He tried to look out through the window plaqued with green mold but could see nothing. He gave up and hung his head. Dark stubble had sprouted up over his lean complexion, but his eyes were starting to clear. He pushed back his dirty brown hair, and a fine cloud of silt showered down before him. Sitting back down, he wolfed down the eggs and bacon using just the blade of the knife. At the end of it, he dry-retched and horsed into a swig, draining the jug. Wearily, he stood up and walked over to the open doorway.

The long-forgotten pear trees sparked fresh white blooms at the edge of the yard by the tack shed. His gray horse looked up at him from beside the front porch, where she stood untethered. He walked down the broken limestone steps and stood next her, fingering her mane. As he released the cinch, she sighed.

He became increasingly aware of the muffled approach of a horse on the sandy trail leading to up to the yard. The gray’s ears perked up as he ducked under her neck and continued working on the saddle. The sound of muddy hooves on the trail grew louder. He hoisted the saddle down, straining as he carried it around her and up to the top of the steps. With a final heave, he dropped it on the rail of the porch.

Just then, a soldier in an imperious blue uniform astride a buckskin mare appeared at the edge of the yard. A yellow braid coiled at his shoulder. As he tipped back his broad federal officer’s hat, he revealed a head of falling blond locks and a trim beard to match. The soldier looked over the house. An eminent ruin, it had a rusting corrugated roof that dangled over the wilted colombage walls of crumbling white plaster and decayed timbers. Broad-leaved finger vines wriggled in at every crack. Most of the windows were broken; the others were opaque with mold. The weathered gray shutters held fast. North of the dilapidated tack shed, a corroded, split-rail corral was slowly being consumed by the rising sawgrass. On the opposite side of the yard, a three-sided smithy and limestone forge stood in abysmal condition. The tongs and hammer hung orderly against the cypress walls, and the anvil sat bolted to a scarred, three-foot water-hickory stump, but weeds sprouted in the floor and the furnace sat cold, filled with a mound of wet slag.

“It’s not Versailles, James.”

“Yep. Ain’t no bourbon in it.”

The officer smiled.

“That’s the truth, James.”

The officer prodded his horse forward through the yard. His mirrored black riding boots shimmered against the side of the buckskin.

“Well, have you been working much?”

“Not since I last saw you a couple days ago, Fletcher. You still mad about that last hand?” Phobetor wiped the sweat off his face with his sleeve.

“I’m not upset, James. That was five weeks ago. It’s Easter this Sunday.”

“Like I said, it’s been a while.”

Phobetor stood leaning against the railing of the porch next to the saddle as his plethoric face beaded with sweat.

“Magnolia not enough for you? Or you come to dig up some new interests this side of the river?”

“Not really. Magnolia is fine. Our nation sees to that.”

“Nation of ours, is it?”

Phobetor’s LeMat revolver hung from a leather thong wrapped around the saddle horn. Fletcher stood up slightly in the stirrups and eyed him closely.

“You know, if you come around to resurrect a war, then you should have showed up a little earlier when I was a little more peckish…but I guess, if you want, I can still oblige you.” Phobetor’s fingers quivered.

Fletcher opened the holster to his revolver as Phobetor slid his hand in his pocket and then slowly dangled out the tobacco pouch from his fingers. The gray horse swished her tail as the two men glared holes into each other.

“You gonna fight with me, or you gonna fight with me? I didn’t come down here just for the aggravation of it, James. I want to talk about playing some cards tomorrow night.”

Phobetor listened as he fumbled the tobacco trimmings into a cigarette.

“There’s a regiment coming down the river, but it’s mainly a few officers from around Lewisburg and Baltimore. I thought we could have a little gentlemen’s game at Magnolia to welcome them in.”

“Sounds good. Shouldn’t be a problem.”

Fletcher’s hand hovered over his pistol. Phobetor lit the cigarette as he kept looking upward, eyeing Fletcher’s palm, which had come to rest on the heel of the gun.

“The problem, James, is that you’re a cheat.”

“Bullshit. How am I a cheat?”

“I’m not sure, but no one wins like you do.”

“Well, then, it’s not the same. Winning ain’t a crime. Surely you can understand that, Colonel. Show me someone who plays to lose.”

“Well, that’s the point, James. I don’t. If you turn up, I want half of what you win.” With that, Fletcher pulled a nickel quart flask from his saddlebag.

“How do ya know I’ll win?”

“I don’t. But if you’re gonna come over, plan on leaving with half. Otherwise there will be a resurrection.”

The cigarette smoke fanned up over Phobetor’s face as Fletcher took a yawning, breathless gulp from the flask. Phobetor wiped his forehead again. He walked down the stairs across the yard and stood next to the mare. He crushed out the cigarette in the sand and extended his arm, and Fletcher passed him down the flask. Phobetor nursed the whiskey like an infant. Gurgling, he reached to hand back the flask, but Fletcher picked up his reins and waved him off.

“Keep it, Sergeant. Take it out of the winnings, but remember to wear this tomorrow night.” Fletcher handed down a large paper package he’d taken from the back of his saddle.

“Actually, Colonel Davis, it’s still Colonel James Phobetor if you’re talking to me.”

“Actually, James, it’s not. Not in this army. Not tomorrow. Not ever. See you at seven.”

Phobetor dropped his head and took another drink from the flask. Fletcher Davis turned the buckskin and nudged her with his boot. Phobetor watched as Davis plodded off down the trail.

Phobetor went and sat down on the poteaux steps next to the gray horse. Pulling another robust swig from the flask, he set it down and picked up the package Davis had given him. He trembled as he bungled the twine on the package, but he eventually got it open, tearing through brown paper. The blue uniform inside was pressed neatly. There was an officer’s coat and trousers, and a crimson sash. He pulled out the double-breasted coat and stood holding it against his chest, extending the sleeve. The two rows of brass buttons down the front scintillated as they reflected the sunlight. He went back into the house.

Taking the uniform to the enormous walnut wardrobe that stood against the back wall of the house, he swung open its heavy doors. His own gray uniform hung pristinely. He hung the blue jacket on the back of the door and stowed the rest of the gear on the shelf. From the bottom of the wardrobe, he dragged out a wooden trunk. Grappling with its iron handles, he lifted it onto the table and opened the lid. Five revolvers sat in the rack, including two New Model Remingtons, another LeMat, a pearled mini-Dragoon, and a hoary Colt Walker with the initials AM engraved at the base of the barrel. A brace of Union and Confederate cavalry sabers were mounted on the underside of the lid.

Leaving the box on the table, he took the wash pan from the kitchen and carried it to the rusty spigot outside by the shed. Kicking off his boots, he stripped while it filled, and then hoisting the pan, he dumped the spring water over himself. The icy deluge scoured every pore of his frame. The long red scars across his back ached with every elevation of the tub as he repeated the process three times before dropping it again to let it refill. In the sanguine light of sunset, he looked like a skeleton wrapped in pale, wet leather, shuddering in the cold. He doubled over and retched.

Wiping the vomit from his chin, he staggered naked across the yard with the basin, sloshing water all the way back and into the house. Setting the basin by the sink, he walked across the room over to the rope bed in the corner and yanked the bed away from the wall. He lifted out the exposed floorboards. A rifle and a carbine in oilskins lay on top of an ammunition crate within the hidden space beneath. Phobetor tore off the greasy rags. The four-foot Whitworth rifle with its trim brass scope had retained its finish. The revolving Colt carbine, though, once intrepid, had suffered. Its muzzle wore a heavy frost of rust, and mold had gnawed halfway through the stock.

From the drawer at the kitchen table, he grabbed a tin box containing a set of wire brushes and a jeweler’s tray of instruments and placed them next to Davis’s flask beside him. He took a long drink and set to work on the ordnance. Within the hour, he had disassembled the entire armory right down to the springs. The cylinders lay by the frames of the revolvers in a line across the table. The Whitworth was torn to the stock, with the breech skeletonized in front of him. In the last of the fading rays of sunset, he lit the oil lamp and kitchen stove, where the greasy skillet still sat. As the waxy lard deformed in the pan, Phobetor routed the cylinders with the wire brush, swabbed the pan with a rag, and then applied the grease to all the cylinders. The thinner oily runoff was then run through the action of each revolver as it was cycled. The lock on the Whitworth received the same treatment.

By this point, Phobetor was dripping with sweat, so he paused for a few minutes to take another few pulls at the flask before examining the action of the carbine. He took it across the kitchen and placed the muzzle in the pyre of the stove before retrieving his black gun belt, holster, and riding boots from the drawer of the wardrobe. Like the guns, they too were reanimated with a varnish of grease and black powder. Still stripped to the flesh, he walked over to the basin, washed his face and hands with a rag, and advanced on the carbine again. As it clattered on the stove, its muzzle glowing, Phobetor grabbed it and a long rasp file from the drawer and took them to the porch outside.

The gray horse looked on as he located a wide crack in the limestone step outside, into which he wedged the gun’s barrel. Wrapping one hand with the oilskin and gripping the file, he braced the carbine at the stock with the other. With the barrel locked into position in the limestone, he began sawing at it beyond the loading lever. For half an hour he continued, until the file finally tore the blisters from his hand. The wall of the barrel was two-thirds severed. He painfully lurched his entire weight against it, trying to wrench the final bridge of steel apart. The barrel flexed gently against his provocation but still would not submit.

Leaving the gun wedged in the step, he went inside and returned with a lead ball in his teeth, a powder horn in his hand, and the flask under his arm. Dropping the powder horn on the porch, he sucked the flask dry and then flung it into the yard. He picked up the file once again and twisted the stock, knifing the file into the barrel again. Phobetor leaned heavily into the stock, and after six quick strokes and a groaning torque of steel, the barrel broke free under his weight, pitching him into the horse. Phobetor held on tight to the carbine and spun around to face the animal. Staggering, he ascended the fractured steps. His equilibrium somewhat regained, he now stuffed the powder into the chamber and spat the ball into his hand. Wavering at the edge of the rail, he plugged the gnawed lead ball into the cylinder and then ratcheted the lever, sealing the ball. He cranked the hammer, and the cylinder rotated. Taking aim at the glimmering flask at the edge of the light, he squeezed the trigger.

The carbine roared, spitting a flame and breaking the stock as the flask disappeared into the night. Phobetor reeled in a circle from the recoil and went sprawling out into the air. Clearing the porch, he soared over the steps and landed in a heap of grease and unburned nitrate, the carbine folded beneath him. The gray walked over and gently rolled him onto his back with her muzzle. As he lay stretched out in the sandy yard, his agonal gasps continued throughout the night, allowing him to shift just enough sour bayou air to survive again until the ritual quagmire of dawn.

Chapter 3: Le Reve

The battleship’s iron hull was graceless as it plowed the whitecaps surging through the muddy river. Its rusty soul protruded through its peeling, black marine lacquer as it rode the channel of the far bank of the Mississippi’s heaving current. The muddy water poured over the main deck as the low-slung ram broached in the afternoon tide. One hundred and sixty-five feet of ironclad ram had been reoutfitted with two shovel engines. Iron I-beam cargo decks had been constructed to suspend a hemp web of rigging, oak barrels, and pine crates lashed into two towers that straddled the bridge and twin boiler stacks. The gunports were open and filled with the gaunt, malarial faces of the crew peering out to catch a glimpse of the city. Strung between the ports was a clothesline, from which fluttered two dozen tattered shirts and a line of moldy, rotting britches.

At the bargette’s helm, Lucius Cephus worked the wheel. A caribe block of a man, he studied the waves, briefly considered what the ship could negotiate, and then resolved to swing the heap around. In the back of the bridge, he squatted low, pulled his moldy railroader’s hat down over his bushy black eyebrows, and hiked his waxed collar high against his black beard. In the distance, smoke from the ovens of Orleans Parish twisted gray threads above the levee.

With a pneumatic scream, the ironclad’s giant motor halted in a cloud of smoke and steam. Cephus’s greasy, black-olive paw expertly shifted the wheel. Like a river monster rolling from some fathomless depth, the swell boiled to a crest above the bow as it plunged just below the murk, and the ship turned to come about in the main channel. The wave surfed into the port like an earthquake, lifting the moored freight vessels above ground level and then dropping them abruptly as the tide crashed into the dock. A wide smile grew on his face as his flotage surfaced, straightened, and then drifted into the current of the nearby side channel. He watched the heads peek above the levee on the horizon behind the dock, and gradually a picket fence of gagglers formed.

With the sun burning off the last of the afternoon clouds, twenty crewmen hustled down to the deck and began casting off the ropes. Silently the booms of two ancient wooden freight cranes began rising from the dock. Beneath their monstrous swinging arms, long shadows floated across the lilliputians swarming to the boat on the wharf, catching lines cast from the crew on the deck. The Reve, its twin engines silent, slid in parallel to the dock and drifted to the moorings with a gentle stop.

The men began stripping the rigging on the elevated decks as the booms stalled in their wide arcs above them. The massive cables played out the hooks, swinging them down to the deckhands. Carefully they tussled, looped the ropes around the hooks, and jumped clear. Like the two tarsi of a giant mantis, the cranes dangled nets packed with crates over the ship and glided them down to the ropes of their guides on the dock.

The ship rocked softly as Cephus descended the steps from the bridge and made his way to the side of the boat, where he looked back to the squat, redheaded engineer peering out from the bridge. He waved, and the engineer waved back. Cephus walked down the gangway to the dock, where two soldiers in a pair of horrendously disheveled navy uniforms were waiting with a wagon. The shorter, fatter driver sat with a gob of tobacco in his cheek and a headful of black curls falling out from beneath his sweaty cap. The taller soldier stood by the side of the wagon behind a bay horse so haggard and full of mange that if not for the tail, it could have been related to him. The man sported a wild, red dust-broom mustache, and he remained leaning against the wagon, tipping his cap as Cephus approached.

The captain stopped just short of the two men. At six feet five inches, he stood before them like a mountain in his green jacket and heavy leather boots. His salty gray eyes peered out at them from under his hat as an ephemeral lull in the afternoon sun dragged on between the three of them. The mustached soldier began to speak, but Cephus brushed past him, jumped up into the wagon, and sat down on the back bench.

Standing for a second with his mouth open, his auburn mustache trembling as it filtered his hot, rank breath, the soldier turned to the driver. The driver looked at Cephus, who was staring out at the river, and then looked back at his partner and shrugged. Wiping the sweat from his mustache, the soldier climbed in and signaled the driver to drive on. The reins snapped against the wet back of the bay, and the wagon lurched as the motionless front wheels grated ten yards across the dock, accompanied by a guttural snort from the bay. Jerking the reins back, the encumbered driver wiped the tobacco juice from his chin that he had spewed out onto the front of his uniform. His partner desperately clung to his hat, and Cephus silently leaned forward into the front bench. Weaving his pythonic arm around the driver, Cephus grabbed the hand brake to release it as the two shaken soldiers repositioned themselves. The taller soldier shot the driver a glance, and they both turned to stare at Cephus. Without breaking his gaze over the river, Cephus motioned them to drive on.

The driver shrugged at his companion. With another slap of wet leather, the bay tightened and launched the wagon forward. Its rusty wheels rumbled across the pier until the wagon turned onto the cobblestones, where it filed in with the other freight carts as they funneled their way down the street and ran through the gap in the levee into the warehouse district that led into the city.

Chapter 4: Shooters

It was late afternoon, and Lucius Cephus sat alone in the back of the wagon on Canal Street outside the imposing columns of the Customs House. The heat of the day was beginning to abate. The two disheveled soldiers now reemerged from the building, climbed aboard, and drove the wagon to the far side of the boulevard. They stopped outside a raised-basement bar whose swaged-oak sign proclaimed it the Rathskeller. A pair of gangly whores adorned with crudely caked rouge and pale-blue eye shadow lounged outside. Cephus and the soldiers passed them silently as they made their way to the door. Behind their misfit, clownish makeup, the ladies seethed as they tried to follow the men into the bar and were met with the door slamming shut against them.

In the back corner of the bar, two officers, both with long, dark beards, watched Cephus as he eclipsed the light from the window in the doorway. The soldiers escorting him waited at the entrance, and Cephus made his way over to the officers, who stood to greet him. The men shook hands and then sat down at the candlelit table. The shadows of the two officers swayed along the damp limestone wall as they addressed Cephus.

“I’m General Allen Rourke. This is Major Allice. It’s a pleasure to meet you, Captain.”

“Captain Lucius Cephus, of Le Reve.”

“Great. Have a drink. What is it, Captain?”

“Gin and tonic. A little lime.”

“It’s nice to meet you. Have a seat. Hopefully this will be straightforward.”

“Good. So, how many rifles do you have in total?”

“Five hundred fifty. Enfields and Lorenzos.”

“Tell me, General Rourke. These guns are de shootas or de rotten?”

“Shooters, Captain. Every one of them.”

Cephus took his drink from the waiter and looked at the goateed officers blankly as his wandering French baritone thundered into the corner.

“I was told eight hundred.”

“The difference wasn’t in condition to sell.”

“What you want me to tell my people, use de forks and knives? A real war needs real guns. Surely you know this, General.”

Rourke leaned back and lit his pipe. Allice sucked at his whiskey and stared up at Lucius.

“Listen, we can only sell what we’ve got. The rest is basically scrapped.”

“You know, Offica Allice, I’m in de scrap business. So since I’m here, why don’t you let me make an offer on de scraps?”

Rourke sat forward.

“Captain, we’re happy to sell you the difference, but they’re being reconditioned down river. If you want ’em, you can pick ’em up. But we don’t have ’em up here.”

Smoke curled through the general’s yellow teeth as Lucius nipped at his gin.

“Seems like extra work. I was told I could get eight hundred if I came to New Orleans. Now that gonna drop de price?”

“How much would you give, Lucius?”

“Seven a half regulars, four on de scraps.”

“Eight on the regulars.”

“No, but I will do four and a half for de scraps.”

Rourke finished his drink. “That’s a hell of a salvage vessel, Lucius. Any chance we could come aboard your ship and have a look at things?”

“Sure, General. You like malaria? Only half of de crew has got de shakes now.” Cephus swirled the ice in his glass.

“What about the other half?”

“They’re in the river, General.”

Rourke cleared his throat. “No chance that other Brooke rifle is still on board?”

“No chance. Probably back east where de tore her open. Listen, I’m in de salvage business, not de mercenary business. It’s an issue of recovery.”

“It seems, then, the salvage business mustn’t be what it used to be, Captain. You know the Big Fish was interested in your Reve.”

“Well, boss, de Big Fish could’ve bought her de same as me. Now, I gave you my offa on de guns. So, let’s stick to de business we’re in today, General. Otherwise maybe I’ll steam to Natchez. They have guns, too, no?”

“That’s right. They do.”

“So seven and a half and four and a half or nothing today, then, gentlemen.”

Allice paused. “Seven and half and four and a half will do.”

Rourke nodded. Allice stood and walked over to the soldiers at the door, and then the three men walked outside. Cephus stood, took a small leather bag from his coat, and dropped it on the table next to his empty glass.

“Have dem load it tonight.”

“It’ll be loaded by eleven. They’ll have the rest at La Hache. Pick them up tomorrow night. Colonel Davis will meet you.”

Cephus nodded and walked out. Allice was walking back across the street toward him from the Customs House. The two soldiers in the wagon sat waiting. The whores were gone. Cephus climbed into the wagon and pointed up the street.

“Fauborg Marigny.”

The haggard bay horse lurched into motion, and the wagon jostled down the street. Rourke emerged from the bar to meet Allice.

“Wire Fletcher and let him know, and have the regiment head out tonight. Give him the money to cover Cephus for the weapons and the boat when you take it. Tell Davis to follow his goddam orders, or he’ll be speaking Comanche this summer.”

“Not worried about that Marabou?”

“No. He’s big, but he is in the wrong business.”

“Why not just take the boat here?”

“If he has that Brooke on that ship, he could level half this city. We would have to level the other half trying to sink it. Cephus knows that. That’s why he wanted the deal here.”

“You want to hold back the rest of the rifles in La Hache?”

“The extra two fifty aren’t even in La Hache. They’re already on Patterson’s second boat heading to Cayo Romano. Consider it a test run, but don’t discuss it with Davis. We’ll have them ship Cephus’s guns when you bring them back, and then you’ll take your regiment up the Red River to Fort Griffin to help Atkins. The Spanish probably won’t put a light on Patterson, but even they can’t ignore something like the Reve.”

“That ironside makes a pretty ornery-looking transport in the Gulf.”

Rourke tapped his pipe against the doorframe.

“It will for little while, but the big wheels are too fired up. The Big Fish will stick that thing in the dark. There are no funds to go picking a fight. We’re not done paying for the last war down here. It’s a damn shame. It was hard enough to sink that boat once, but if Captain Cephus doesn’t cooperate, sink it again.”

Chapter 5: The Birdhouse

The rickety wagon banked and rolled up over the stone curb as the gaslights flickered on in the Fauborg Marigny. Their amber shafts floated down Frenchmen Street all the way up from Decatur to Founders Park, where the remaining veterans staggered into the lamplight for the evening.

Cephus jumped from the wagon, gave it a smack, and walked up to the swaggering blue-and-white iron hotel frontage on the corner of Chartre, where the brass notes of the automated calliope whistled out from the blind alley at the side. He barged through the door, past the red velveteen curtain hanging over the entrance, and then stopped. A thunderhead of smoke gathered at the end of the hall, where two burly Creole men sat, quietly passing a spindly stick pipe back and forth. As Cephus came toward them through the billowing cloud, one of the bouncers rose, took off his chamber-pot hat, and opened the door in the side of hall. A bellowing calfskin drumbeat rattled up the stairs and through the floorboards of the hallway. Cephus passed him a faded folded bill.

“Busy yet?”

“Always busy. We big on Reconstruction these days.”

“Aren’t we all? Losing de war was de best thing that happened to dis town. She around?”

“She down there.”

“Any blue shirts down there?”

“You bet, Lucius. At the Birdhouse we got a new policy — big blue shirts chase the little loose skirts. Nobody lose, nobody gets hurt.”

Cephus smiled. “Anyone gonna hurt me?”

“Not if they want to see New York again, Lucius. Besides our new policy, we also still pay respect to and abide by our first and most basic policy at the Birdhouse: don’t cock your own gun, ’cause if you do, it won’t be no fun.”

In the corner, the raucous laughter of the Creole bouncer sitting in the chair turned into a fit of coughing, and his blood-choked eyes began to bulge. The doorman took the pipe from him and handed it to Cephus, who scorched a long ember through the pink resin. Stuffing another bill into the doorman’s front pocket, he handed back the pipe.

Cephus dropped down the stairs to a street-level chute spanning the alley from the hotel to an entrance into the brick warehouse next door. Outside, the automated calliope wailed as it cranked out “Zouave Cakewalk,” and the notes fused with the pulse of the drumbeat pounding through the door in the side of the warehouse. Cephus felt for the handle, and as he opened the door, a thermal belch of blood and rum blasted out with a roar from the crowd of soldiers that packed the warehouse to its walls. A forty-yard square of blue-coated troops bayed around a brick pit littered with the corpses of dead and dying dogs. Within opposite fenced corners of the pit was a pack of chained, wretched canines — this was where the dog handlers sat.

Working his way around the crowd, Cephus could see a horsish, red-tailed black mongrel being released by his handler as a trio of stocky, lock-jowled brown bulldogs emerged from the far corner. Although it was flanked easily, the mongrel wasted no time mauling the slowest of the three bulldogs, snapping its limp frame ten feet into the air. The other two bulldogs had already latched onto the mongrel’s back legs by the time the corpse of the first bulldog crashed into the first row of soldiers on the ledge of the pit. The mongrel cleverly rolled, forcing one of the remaining two bulldogs on his hock to release him. Grappling the dog at the jaw, it tore its mandible from the socket and in the process flung the animal to the brick wall, where the beast collapsed. The last of the three assailants hung on in futility near the rump of the destroyer. The red tail swished frantically as the mongrel ripped the bloody hide from the last bulldog’s wrinkled face, gimping the animal to release and wander blindly to the opposite corner, where it was let in the fence by a handler, only to be clawed apart by the remaining dogs as the crowd broke into rapturous applause.

Cephus backed away to get a drink from one of the long bars mobbed with soldiers. Constructed from stacks of rum barrels and oak planks, these bars stood along the walls, where hundreds of pilfered mirrors hung against the crumbling, red-clay brick. Creole barmen whetted the horde. In each corner of the crude stadium hung enormous, oddly matched, rose-glass Murano chandeliers. Beneath them, whole tribes of motley whores stretched out on shabby sofa loungers arranged in a series of circles. Cephus recognized two of the women as the whores he had seen earlier in the day. They looked worse than ever. The gradual decay of their makeup did little, however, to deter the drunken soldiers sitting next to them.

High above the pit, a massive bottomless birdcage was suspended on chains. A sallow whore sat on the perch, naked except for a radiant sheen of sweat and a bata drum clenched between her legs. In perpetual revolution, her flashing palms unwound a primal rhythm as the red-tailed mongrel limped back to the corner. A pair of boys cleaned the ring and dragged off the dead animals. The barman handed Cephus a short glass of rum, and he pounded it down in a single swallow. His glass was refilled, and he leaned against the bar watching a feathered troupe of dancers as they made their way through a side entrance. The sea of blue uniforms parted, and the dancers made their way straight to the pit and descended the wooden stairs. Their peacock headdresses waved as they linked arms and formed a ring that undulated to the cadence of the drum. Accelerating into a rolling conga, the feathered dancers released arms and pirouetted away from one another. A rumbling crescendo began to build from high up in the birdcage and spiraled down to the crowd as the shouts from the hollering troops intensified. In the pit, the gyrating women obliged by raising their solitary feather boas high above their heads as they danced. A voracious howl went up from the crowd, and Cephus lit a cigar he produced from inside his jacket. Over the next fifteen minutes, the routine continued through a series of progressively more erotic locomotions as the crowd vacillated between hushed disbelief and waves of brutal expletives at the completion of each outlandish movement of the cycle.

Finishing his third glass of rum, Cephus crushed out his cigar on the ground. He eased over to one of the side doors, flashed another note to the bouncers, and slipped out of the warehouse into an alley. From there, he climbed a metal staircase to the balcony of the neighboring house, which looked down on the corner of Royal and Frenchmen Streets. At the end of the gallery, clad in a cyanic-green robe and smoking a cigar, a large Creole woman with wild gray hair sat in a rocking chair. Her blue eyes gazed down at the toxic veterans as they wandered through the shadows of the palm trees in the park, straggling, hovering in and out of the aura of the lamp on the corner.

“Am I late, Madame Maymel?”

“You never have been…and probably never will be. Late ain’t your problem, Lucius.”

He walked across the porch and sat down next to her on the floor, stretching out his long, heavy legs. “You have a full house tonight, Madame.”

“Always do these days. I give the people what they want.”

“Even if it is not so agreeable for the animals?”

“Sometimes, Lucius, we do not have to agree.”

“It is true. This is de way people want it. I suppose if dogs are bred to fight, then that is what they will do. A man is bred de same.”

“And a woman? What about her?”

Lucius smiled. “Even I know not predict a woman…it is safer for us dogs to be in de pit.”

She laughed and sent a raft of smoke plunging out over the balcony. Looking down on him, she reached behind his ear and scratched his neck. Lucius leaned forward and smiled, pretending to pant like a dog as she moved her hand down his back and rubbed his spine between his shoulder blades. She sighed, paused, and drew off another long wave of smoke before picking up from the floor a bowl covered with a red tartan rag. From under the rag, Maymel pulled out a green cricket and wrapped it in her long, wrinkled fingers. Plucking off its hind leg, she put it on the cloth and dropped the cricket into the coffee can on the floor beside her. From next to the can, she lifted a bottle of absinthe and passed it over to Cephus, also handing him a glass. He poured a short one, slouched against the wall, and looked up at the pale lavender wisteria blossoms hanging over the copper roof. The absinthe seared his tongue as it trickled into the corners of his mouth. The calliope down the street was silent, and the palms across the road became still. Maymel continued to amputate the rest of the crickets’ legs until she sat with a pile of them on the cloth in her lap. The half moon had risen and was cresting into the northern horizon of the violet sky.

Lucius finished the glass and refilled it to just over the brim, forcing him to suck down the top half to avoid spilling more. He looked up at Maymel, who smiled, took his free hand, and pricked one of the veins in his wrist. She held his hand steady until the dripping blood filled a small vial. She capped it and laid it in her lap before dumping the pile of cricket legs back into the bowl on the floor along with some withered tobacco from a pouch that hung around her neck. She knocked in an ember from the cigar. It smoldered briefly and then conjured a blue flame. Carefully, she poured the blood from the vial onto the flame, which hissed, disappeared, and then reemerged. Putting the vial down, she sat back in her chair with the bowl in her lap, letting the smoke from the bowl crawl up to her face.

Lucius took off his hat, rubbed his face, and then replaced the hat. With a steady hand, he worked his way down the absinthe in his glass. The image of the moon pulsed before him, and Maymel craned her head toward the sky. The contents of the bowl smoldered for half an hour as the crickets in the coffee can scratched around on their sides. Finally the flame dwindled. She put the bowl back on the floor and began to speak in a low, sorrowful drawl.

“Lucius, do you remember when I found you stuck in de bottom of dat boat in de bottom of de river?”

“I do. Le Bete.”

“That’s right. That is the one.”

“I had crawled into a pocket of air…it was my first time in America.”

“Well, if I can find you der, I can find you anywhere.”

“I hope dat’s true. Without you, I am lost. You are my guide, my cheval.”

Maymel took the glass from the floor and poured herself a drink. Taking a gulp, she sat back in the chair and looked out at the moon.

”Well, I wish I didn’t, but now I know for sure, Lucius. You will not be back. It’s what I have seen tonight.”

“Is the cheval always right? Is it I am sailing this way, or is it de wind blowing me?”

“Lucius, as long as I have ever known you, I have never seen a wind that could move you. But it is different. You have already made all your choices.”

“Is this just de crickets chirping?”

“Well, ’tis and it ain’t, Lucius. If you don’t believe me, why did you come?”

Lucius took off his hat and rubbed his face once more. His straight black hair fell over his face, and he pushed it back.

“And you, Maymel, what happen to you?”

“I’ll be around for a while. Someone has to give de people what dey want, and it’s not all rum and feathers.”

Lucius slid his cap back on and stood up.

“I know this. I also know that de ears are the most dependable part of a whore. You will find me somehow.”

“Yo no fool, Lucius Cephus. But yo just one man. You gonna need help. You may rule de waves, but you do not rule the world. Remember that. Lucius, do you have de gun on dat boat?”

“It is der, and ready. Dey inquired about it, but dey sound afraid. If dey try anything, it would be…suicide. The ship has no match in de water. Now, could you tell me, where is de rendezvous to drop de guns?”

“Casilda. South coast. Dey will meet you in a fortnight.”

Lucius put his hand on her shoulder and smiled. He looked down to the banquette in the distance, down Royal Street, where three men had stumbled as they were chased out of a bar; they were shouting at the proprietor.

“I will be der. Tell dem, when you see dem. I have my own cirque to oversee, Madame, and de clowns are out of the wagon.”

She stood and hugged him.

“They are other horses to guide you, Captain Cephus. You will have to folla dem for advice. I done all I can.”

“This is true, Maymel, but you are my only cheval. We will meet again. No matter what the crickets say.”

Lucius turned and walked to the end of the gallery and down the iron stairs, jumping over the rail to the street below. One block down Royal Street, three men stood opposite a man who was cursing and pointing at the shortest of the men, who had a headful of red curls. Cephus recognized the red-haired man as his engineer; he was standing alongside his two lanky Haitian deckhands. Lucius made his way to the far corner of Frenchmen and Royal, where he stopped and lit another small cigar. The barman finished his torrent of abuse and walked off the street back into the restaurant, slamming the door behind him.

The engineer went over to the curb and sat down on a fruit crate. The other two men stood in the street laughing. From a pack on his shoulder, the engineer produced a concertina and began winding into a bawdy rendition of “The Blackthorne Stick” while the two other men hopped to the jig. The tune accelerated, and the dancing picked up some semblance of rhythm as the men in the street worked furiously to keep their heels above the cobbles. Abruptly, the bar door burst open and the owner barged back out, crossed the street past the dancers to where the engineer sat on the crate, and stood above him, raging diminutions. The engineer sat quietly, holding the instrument and looking at the ground. When he was done shouting, the man stomped off back toward the bar. Just as his fingers reached the latch on the door, the concertina burst into another number.

Turning from the door, the barman sprinted across the street and kicked the crate out from under the engineer. Clinging to the instrument as he hit the ground, he rolled away from his assailant, all the while speeding up the tempo of the jig. The barman chased him in a ring around the street lamp, but the engineer’s stocky legs kept up a frantic pace, and he could not be collared. The dancers lay on the pavement, gasping in hysterics. After a few quick circles, the two foes stood panting opposite each other on the curb as the last few notes of the song trickled out into the night before the box went silent. At last, the barman turned again toward the door, only to hear the concertina crank up again as he went back inside the bar.

Meanwhile, the wagon had arrived at the corner. Lucius climbed aboard and sat on the front bench next to his intensely inebriated driver, who hiccuped profusely. His partner lay stretched out and moaning, his feet hanging out from the back of the wagon. Suddenly, down the street the barman reappeared, bursting through the door with a short-barreled shotgun. The two dancers stood frozen. With the gun at his side, the barman marched straight across Royal Street and proceeded to taunt the man with the concertina where he sat on the crate. Rising, the engineer set the concertina down and knelt on the bricks. The barman shouted as he lined up the shotgun to the man’s shoulders and kicked him to the ground. His friends remained motionless. Stepping back, the barman kept the barrels beaded on the engineer’s trembling red curls.

A short distance away, a silent red ember shot from where Lucius sat in the wagon at the far end of the street. Trailing a ribbon of smoke, the flame floated higher, climbing quickly and arcing just above the second story of the dormer houses, etching an iris-hued, blazing streak into the night sky. The flame grew as it descended and traveled down the empty street, where it exploded across from the restaurant. A shower of iridescent flames spread down across the pavement and leaped upon the man with the shotgun. He dropped the weapon, covered his face, and then ran screaming into the building while the other three men rolled in the filth of the street to extinguish their burning clothes. Scorched like burnt grass, the men peeled themselves up from the cobblestones.

The wagon rattled down the street toward them, and the weary bay hauling it skidded to a stop in front of the restaurant. Cephus rose before them in the wagon with the flare pistol resting on his shoulder.

“Bring de gun, and be careful with dat goddamn ting. It may kill us all.”

Their clothes still smoking, the men grabbed the gun and the concertina and then clambered into the wagon. In the weary light of dawn, the shaking driver whipped one more snort from the bay, and the wagon plowed forward. They clattered down Royal Street, made the last turn onto Esplanade, and then turned right onto Decatur, where Cephus again rose to his feet in the back of the rickety wagon. Against the gray morning breaking in the east, he could make out the plane of the river and the silhouette of Le Reve as it rocked softly in the harbor beneath the booms of the towering cranes.

Chapter 6: Blades

Thomas Sands’s withered fingers held the parchment of the deed up to his wire spectacles, which rested on the end of his hooked, white nose. Phobetor sat across the table from him in the mercantile store on the main street of La Hache.

“You serious about leavin’?”

“Serious as a butcher in a hog lot.”

“How’s your Comanche?”

“Ain’t so good. Definitely not as good as my Mexican, but it’s a damn sight better than your arithmetic. How do you figure on a hundred for my outfit?”

“Well, the wagon’s fifty. Impedimenta, another fifty. You want that animal in this deal too, James?”

“Nope. That’s all I got left. Man without a horse ain’t got much hope in this world.”

“Hope doesn’t figure into it, James. Cavalry is dead. You gotta move on. Repeating rifles killed it. Trains killed it.”

“She’s worth more than this store, Thomas. I don’t plan on requiring much to get started. Just a seat tonight will do. Can’t wait on a train, anyhow.”

“As bad up as you’ve been lately, I guess I still never thought I’d see Colonel Phobetor dolled up as a federal. Old Tom Green would turn over.”

“Probably so, God rest him. Well, if it helps, they demoted me to Sergeant.”

Sands studied the deed as Phobetor looked over the table and out the window of the dusty front room of the mercantile. Straight-handled shovels, hickory axes, and long cane knives oiled to the tang hung along the north plank wall behind the till.

“Four hundred.”

“Horseshit, Sands. It’s at least twelve hundred. The place backs up to Long Bayou. It’s got coastal access. You know this. Quit wasting my time.”

“Ideally, James, you might be right, but they’re cutting cards at nine. So I’ll give you six, but that’s it. Otherwise you’ll have to take your offer and see what you can get from those boys from Lewisburg.”

“Sands, you’re the reason we lost this war. Ransoming your own goddam people. Never mind the federals — at least you could tell who they was with.”

Sands sat took off the glasses. He placed them carefully on the table and then sat back in his chair.

“Well, that’s one way to look at it. Just because you looted that stockpile at Brashears doesn’t make you a hero. Where do you think those Yankees got all that gear? Vermont? More like Plaquemines Parish, and I haven’t seen a nickel handed over from any government since. It’s rich when you want to run your mouth. Colonel maybe, corsair definitely, worthless drunk, as sure as I am still alive and breathing. You’ll get six, and you’ll be glad of it. Maybe they won’t take it off you before they put a bullet in you tonight, but you ain’t going to win much, in case you didn’t know yet. Even if you’ve gotten a seat and a blue shirt somehow, they’re never gonna let you walk with more than your hide and that horse. I won’t give you more than six. I’m tired of donating to every fool who shows up with a gun and a license to make life worse for the rest of us. Can’t see how a man could stoop so low as to drag himself around country he cheated twice.”

“Maybe getting looted isn’t such sacrifice Tom. What you know about havin’ skin stripped off your back? Cause I can show you.”

“Just because you were in Pulaski don't make you immortal James. You switched sides soon as you could to save what was left of your hide.”

“Well sir I am alive to tell the tale. Most of them boys ain’t. I did a lot to get them fools along the Ogochee to pack it in instead of dying in a swamp for because some son of a bitch with land said they had to.”

“Everyone has a choice. You made yours. Anyway, your jaundice will not change today. I can see that here looking at you.

Sands shook his head and continued.

“You're probably right to carry on drinkin and fighting at this point. It doesn’t matter who you're shooting at these days James, someone else will come looking for you. Requital cuts deep as those blades. Everyone wants to think things end with surrender, but we are all still in this squabble. None of us started it. We are still just the flesh that hasn't been peeled.”

Phobetor sat across from Sands, shooting him a sour glare.

“You done cluckin’?”

“I am but this offer isn’t going to hang around all day waiting on a drunk, even if he does maintain a rank of some meager description.”

Phobetor stood and tapped forcefully on the table. Sands leafed through a pile of notes and slid over six moldy bills, which Phobetor stacked on the table and folded into his pocket. He walked over to the wall and took a cane splitter from where it hung on a rusty nail. Turning back toward Sands, he inspected the edge of the blade.

“If I can lead eight boys from Albuquerque between the Apache nation, across Texas, and through the bayou in a feed trough and whip the whole southern Yankee corps, then I can pretty well handle myself in a game of cards.”

Sands sighed and got up from his chair.

“I’m sure they have other interests on the east side of that river beyond you, and I doubt they asked you along for your charm. You can keep that blade. It’s on the house, but it ain’t enough to cut down a whole regiment.”

Phobetor put the knife in a canvas sheath that sat in a stack beside the till and then slid it inside his jacket. Taking out his tobacco, he rolled a cigarette on the counter. Sands put his glasses back on and walked over to the door. Lighting the cigarette, Phobetor stepped over to the shopkeeper, who stood looking out at the stream of federal troops filtering up the street. Sands turned back to Phobetor, who had extended his hand.

“It’s not gonna be all hearts for them tonight either, Tom.”

Sands shook his hand. Phobetor replaced his hat and ducked out of the shop. Down on the sandy street, the gray nervously eyed the parade of blue uniforms. Phobetor unhitched the harness to the wagon. Reaching into the back of the buckboard, he then took out the saddle from where it lay next to the hammer and tongs. The gray relaxed as he threw over the saddle, secured it, and climbed up. He turned the horse to file in with the column of soldiers.

“Has that horse got a name, James?” Sands stood in the doorway of the store, cleaning his spectacles.

“No.”

“Why not?”

“Didn’t give her one.”

“Do you think you’re really clever? Maybe I should cancel our contract.”

Phobetor kept his eyes on the column of soldiers and dragged a few clumps of dirt from the horse’s matted mane.

“Ain’t much on names. They’re bad luck.”

“How do you figure?”

“Every horse I named has died.”

“That’s hardly a surprise, considering your luck, James. How long do you reckon a horse should be expected to live, exactly?”

“Well, ain’t none of ’em died bald or toothless, and they wasn’t wrinkled, either. Fact is, of about the last dozen, I’ve had four shot from under me. Six lamed up, and I shot them myself. One drowned on me, and one got poisoned.”

“Poisoned from what?”

“Drankin’ at an alkali lake. Got the damn rigors on me, and I had to shoot him, too. So I guess, really, that’s seven lamed and shot.”

“So, you’ve shot seven of your own horses, and that’s why you won’t name them?”

“Well, I ain’t no preacher, and I wasn’t gonna hold a service. When they’re dead, I get off.”

Phobetor patted the gray’s neck. “This one’s got a tough chaw. I like that.”

Sands spat on the floorboards. “Are you an expert on tough, James?”

“I’m an expert in cards, ordnance, and horses. In that order. The first two I can fix. The third one is just knowing when you need a new one.”

Phobetor turned his horse toward the road.

“Can that Whitworth still sing, Colonel?”

Phobetor halted and turned to see Sands out on the raw plank sidewalk, pointing to the brass scope peeking out from the leather scabbard under Phobetor’s saddle.

“Sangs like a bird, Mr. Sands. If you listen for it, you can hear it a long way off.”

Phobetor turned the horse and gave it a dig, and they took off at a lope. They soon caught the column of soldiers and fell into step next to them as the troops marched to the dock to wait their turn for the slow tug ferry taking the men to the west bank, where the rest of the unit waited on the dock of the Magnolia estate.

Chapter 7: Stakes

The Creole lilies had sprouted early, and their white petals carved with fuchsia shafts dotted the two rows of yuccas that lined the red-brick path leading from the gravel circle of the drive to the titanic white columns at the front of the Magnolia house. Fletcher Davis sat smoking an orange maple pipe as he surveyed the estate from the wicker chair at the corner of the sun-washed veranda on the third-story balcony. The silty vermilion road to Magnolia stretched out straight as a shot on the chersonese as it rolled through the bright-green knee-high sprouts of the cane fields to the oscillating sawgrass riverbanks on the horizon. Like threads of twisting blue yarn spun out along the sandy delta road, the two columns of the Eighty-First Pennsylvania had been making their way from the dock along the road to the house since the better part of three in the afternoon as the ferries shuttled the unit from the east bank at La Hache. Davis had made out the diligent form of Allice from the time he’d appeared at the head of the regiment. His black walking horse flagged out as he led them along the road, stopping every fifty yards to let the column catch up, only to take off in another series of fluttering licks as he meandered up ahead to scout the ditch on each side of the road.

As the rider closed within a quarter mile of the house, Davis rose and took his pipe over to the rail. Allice arrived at the stone pillars at the head of the drive and stopped in the shade of the live oaks that guarded the final approach to the house. The troops shuffled their way onto the grounds and down the drive around the south end of the house as Allice stood along their flank in solemn inspection. Winding their way past the empty slave quarters, the head of the column halted at the far end of the field beyond the house opposite the well, the smokehouse, and a set of three white cane barns. The soldiers trickled in for an hour as the lemon sun sank behind the house and melted into the horizon as a crimson wave washed across the sky. The kerosene lamps were lit in the front rooms of the house, and the twelve-foot glass windows shed a rippling glow over the blue shutters. A dozen officers milled around the porch, laughing and smoking on the soft linen couches near the stems of the white molded laurels crowning the oak door at the front porch.

Allice came in from the gate, dismounted, and handed the reins to the attendant. He looked up to see the shadow of Davis’s silhouette, its arm extended and waving down over him in the failing light. Ignoring the brisk salutes of his officers, he marched across the porch through the doorway, where he was detained. In the foyer, servants crowded the Sylacauga hall laden with silver trays of hors d’oeuvres. Allice stepped wide of the chaos and trotted up the spiral staircase. On the second floor, another throng of waistcoated staff choked the parquet floor of the ballroom, which was littered with card tables. Steadying his saber at his hip, he scaled the last flight of stairs to the top of the atrium, where Davis stood swirling the vestiges of his cocktail in a lowball while leaning on the walnut rail post. Allice saluted him as he arrived. Davis raised his glass and then sloshed the contents.

“Major Allice?”

“Yes, Colonel. I think you received the correspondence from Rourke.”

“I did, Major, and I have some questions regarding his intentions. However, maybe we should get a few things clarified before we investigate the nature of your visit.”

“As you wish, Colonel.”

“Well, my first question is, how long have you been riding that four-legged ostrich that I saw jogging down the road?”

Allice sighed and then took off his gloves, folding them over into his belt.

“It was a gift. My brother-in-law found him after Chattanooga, saddled and wandering by the road. Looked like he hadn’t eaten in a week. He’s got a fine tilt gait, though, and it makes things easy.”

“Does he have any military inclinations, Major?”

“He’s got more stones than a powder mill, Colonel. That lick disappears when you dig in. He’ll go over a cliff if you want him to.”

Allice walked past Davis over to the white-clothed bar and dumped a handful of ice and a dark swirl of oak whiskey into a glass. After taking a sip, he went to the doorway of the balcony and looked out on the road to the dock.

“Don’t worry yourself too much about that horse. Since you’re semi-retired, why don’t you let me be the judge of any soldiering that needs to be done on this campaign? I would hate for you to have to freshen your own glass twice. Rourke wanted this to proceed as a buyout, not a personal annex.”

“He could’ve told me that himself. Did he send the funds?”

Davis walked out on the veranda and sat back down in his chair. Allice sat on the sofa across from him.

“He did. But this whole thing needs to stay off the map. He wants it that way, and the Big Fish does, too. Understand?”

“I understand just fine. But it’s not my fault Rourke and his patron have let things get sour. Their plan for the reacquisition of this boat is not the strategy we need tonight; I can assure you.”

“Well, Colonel, why don’t you let me delineate the general’s orders before you speculate a little too much further?”

“Proceed, then, by all means, Bill.”

“It’s simple, for a change. When Cephus arrives, we have him down to the house and explain that the government is going buy him out or he’ll be arrested for trafficking. He gets paid, but that’s it. It’s the government’s boat again. He surrenders the contraband, and we offer him passage back to New Orleans.”

“What if he resists?”

“Resistance would be ridiculous. He’s getting compensation that is more than generous, considering his crime. Anyway, putting up a fight against a whole regiment would be suicide. He can buy another salvage boat. It’s an offer than defies resistance.”

“What happens to the boat?”

“Rourke will send it up the coast. They want it back in dry dock. I think they might sell it to the South Americans. The weapons are to be sent west against the Comanche and Kiowa.”

“So, we are buying back our own weapons. And the two-hundred-foot gunboat — the one that took a dozen of our own ships to sink — will be decommissioned? You know, we might need that ship if the Spanish become more aggresive.”

“That’s true, sir, but there is no cane in the barn right now, as they might say down here at Magnolia, and that’s the word from Rourke. They don’t want Cephus instigating the Cubans. Anyway, orders are orders, and you have to follow them just the same as I do.”

Davis knocked back his drink, clattering the ice against his teeth. Having drained the whiskey, he set the glass on the table.

“That’s true, but maybe I can offer you an alternate solution, one that parallels our instructions but is perhaps a little more handsome for everyone involved.”

“I’ll listen, but we have our instructions.”

“What do you know about Cephus?”

“He’s a ship wrecker, salvage mainly, Haitian…trying to move a few guns on the side. That’s about it.”

Davis rose from his seat and walked back into the house. He returned with a sidling gait that was exaggerated by the navy coat draped about his lanky frame. It swayed as he sat back down with the bottle of whiskey from the bar nestled in the chair at his side.

“Well, he wasn’t always a wrecker, because the wreckers originally started out as fishermen. Fishing in the Caribbean, especially near Haiti, lingers just enough so that a man can make a living, but nothing more. Over the last century, wrecking grew as shipping picked up. Those fishermen who had once been part-time wreckers started doing it full-time. They found out that all the obstacles they faced as fishermen generated work as wreckers. Squalls and reefs meant salvage from the floor of the ocean. Many fortunes were made. As time has gone on, though, more boats have become steamers, maps have become more precise, and the vessels have become less susceptible to those most basic elements. Slowly, over about the last ten years, the wreckers who had risen from fishermen have once again found themselves with just enough work to survive, but nothing more.”

Allice finished his glass and waved for the bottle, which Davis reluctantly surrendered.

“So they’ve switched to moving weapons?”

“Apparently yes, but remember, Bill — at base he’s a fisherman, and he’ll troll for what he can. So why not let him? Why not let Cephus throw out the nets for a little extra money tonight at the card table…and if he does, maybe we won’t have to buy back our boat. In the right type of situation, he could end up just handing it over.”

“He would never risk it. All he needs is to collect the guns and head out.”

“You never know. Cephus is already fool enough to come down here. If we spread that money out on the table and he really digs in, maybe he’ll be willing to go over the cliff, as you say in Lewisburg, apparently. Then the money doesn’t have to be surrendered to a reprobate, the boat and the weapons can be shipped out, and the world will have one more fisherman.”

“What if he doesn’t go for it?”

“Well, then we can follow orders, Major, and when you return that boat, you can ride that ostrich all the way up the Red River this summer. But if it does work out for us, you can go back to New Orleans to give Rourke the money back to return to the Big Fish. In that case, I doubt you’ll be learning much Comanche this summer.”

“What’s your end?”

“Rourke will get his money back, but he won’t be getting any extra silver from that Marabou. That stays at Magnolia.”

Allice looked into his glass and then back at the smiling countenance of Davis, whose wide, curling blond mustache shimmered in the light scattered on the porch from the doorway. Finishing his second whiskey, he put his glass on the table between them.

“Not sure if this is heresy or initiative, Colonel, but I am willing to experiment with any plan that means we don’t have to pay a thief not to behave like one. I also don’t fancy leaving my scalp on a greasy lodgepole up on the Llano this summer, either — I don’t care if it’s the Big Fish or any other big wheel giving the orders.”

“How do you intend to cut the cards tonight?”

Davis leaned back into the soft folds of the cushions. The wicker reeds creaked as he rested his arm back on the bottle.

“I have someone to take care of it. He’s the best I’ve ever seen. Couldn’t hold a thought but to drink and shuffle, but I will tell you — his routine is as smooth as a velvet glove. He’s a true blackleg. Still can’t spot how he does it.”

“You sure he’s up for it?”

“Don’t worry about him. Cheating is the only thing he’s ever done reliably. The dealers know. Phobetor will do the rest.”

Chapter 8: The Songs

The remaining embers of the cook fire smoldered behind the shoulder-high stone wall of the Magnolia cemetery. Next to a half-dug grave and a mound of dirt with a shovel in it sat Phobetor, who was gazing east over the moldy limestone wall with his Whitworth in one hand and a greasy, half-charred chicken wing dangling from the corner of his mouth. The hobbled gray horse hopped among the broken, sunken oak headstones as it wandered between the fading patches of crocuses that checkered the graves, ripping the tender shoots of fescue from the soil for its dinner. The warm spring evening set in on the estate and flushed a breeze in from the river, blowing the sawgrass on the riverbank on the horizon just enough for Phobetor to make out the shape of the gunboat as it sat idling at the dock.

Through the scope of the Whitworth, he had watched the buckboard wagon as it brought the colossal man from the boat down the road from the river, stopping at the drive to let him off at the main entrance. The lens was able to gather just enough light from the rising moon to make Davis out as he swaggered down the stairs to greet the immense figure of the man as he arrived. Tracing them through the house as they passed from window to window, Phobetor watched as they made their way to the drawing room, where they sat, smoked, and drank cognac for the better part of an hour.

He pulled back from the scope and spat the charred bones onto the ground. Walking over to the horse, he returned the rifle to its scabbard and unhobbled the horse. The ground was littered with fluttering gray-and-white pinfeathers of the chicken he had caught behind the barn and gutted in the cemetery at sunset. The sorghum in the jar sitting on the black rock of the fire ring was layered in an amber band by the coal bed. Phobetor led the gray over to the fire and picked up the jar with a rag. He supped off the thinner fraction and then raised the jar above him to coax a large dollop to the edge, where it lingered maddeningly before plopping into his mouth. As he swished the big drop around with his tongue, he lowered the jar and allowed the gray to hook its head in for a lick of the syrup. After it had lobbed in a big tongueful, Phobetor pulled the glass back, licked the edge clean, capped the lid, and threw the jar into his saddlebag.

He walked the horse out of the gate and around the cemetery in the shadow of the stone wall to a stand of rotting oaks just north of the house where the original homestead had once stood. Phobetor wrapped the rein around a low branch and then stroked the horse’s neck. Lighting a cigar, he walked over to the east side of the house and waited outside the kitchen until one of the cooks brought out a tub of dishwater to dump on the back lawn. Easing his way in through the doorway, he ghosted past the servants preparing the confit and oysters and along an oak table that ran the length of the room. Opening the door to the hallway, the line of officers was already migrating slowly to the drawing room. Phobetor grafted right along.

They filed in around the great green-silk-lined walls. Allice and Davis sat at opposite ends of an overstuffed sofa in front of the six-foot fireplace, where a sycamore limb burned brightly. Cephus, clad in an old, black velvet suit with a yellow cravat, sat in a nearby armchair. A bottle of cognac reposed on his knee, and a snifter in his right hand floated gently up to his lips from time to time. On a small elevated stage in the corner, a decrepit, white-haired Cajun man stood quietly in a white shirt and a pair of pale-blue cotton trousers, his thumbs looped under his black suspenders. Two waif minstrels sat behind him, one with a guitar and one with a fiddle. The old man tapped his boot, and then, in a high tenor, his raspy cords strained out the lonely notes that resonated through the belly of the house.

When the wind blows free

I smile at the moon

And she smiles back at me.

In a hundred years

Beneath the stars above

I will be back to this

This land I love.

As I travel south

To the Plaquemines

from La Heve down to New Orleans

This river rolls on to the sea

And like a mirror it shows

Her face to me.

In my heart

Where love sleeps tonight

My course runs true

guided by her light.

When I wake up

At the rise of dawn

Though her smile fades

The river flows,

And my boat sails on.

Pausing for a second and then wiping his forehead with a rag, the old man nodded to Cephus.

“And now, by the request tonight of our host, Colonel Davis, an encore en français.”

A cool bayou zephyr floated in through the open windows, billowing the long white curtains away from the windows and sweeping the cigar smoke across the room. The old man tapped his boot, the guitar and fiddle followed in, and once more he strained his way through the Acadian melody.

lorsque le vent souffle libre

Je sourire à la lune

Et elle sourit en arrière de moi.

Dans une centaine d’années sous

Les étoiles au-dessus

Je serai de retour

à cette terre j’adore.

Comme je voyage vers le sud

En direction de la Plaquemine

De La Heve jusqu’à la Nouvelle-Orléans

Cette rivière s’écoule vers la mer et, comme un miroir,

Elle montre son visage pour moi.

Dans mon cœur où l’amour dort

Ce soir mon cours exécute vrai

Guidé par sa lumière.

Lorsque je me réveille

à la montée de l’aube même si son

Sourire s’estompe cette

Rivière rouleaux

Et j’ai naviguer.

A round of applause followed, and several bottles of brandy were passed around the rows of officers lining the walls. The two waifs continued by starting up a waltz as another inferno of cigar smoke gathered. The officers laughed and passed the bottle. Phobetor snatched a half-empty glass sitting on the windowsill, loaded it to the top, and then handed the brandy along. Cephus was red-faced, glassy-eyed, and grinning as he watched the fiddler hopping around the stage as he played. Allice and Rourke were equally ennobled as they drank and slouched in the sofa. The fiddler continued and wound the strings fast to his cheek. The guitarist struggled to keep pace, and the officers began to holler and stomp. Phobetor finished his glass and watched Davis as he leaned over to hand Cephus a cigar. The waif could quiver the bow no more, so he drew off the final notes and then leaned over to take a bow. Cephus, Allice, and Davis all stood and clapped. The gallery squalled as they circulated the brandy once again. Allice and Cephus sat back down as Davis remained standing and walked, wobbling slightly, over to the fire, where he set his glass down on the mantel.

“Gentlemen, thank you for coming tonight. It is our pleasure to host our honorary guest, Captain Cephus. It takes a hell of a man to sail a ship back up from the bottom of the Roanoke…where Lieutenant Carling put her.”

A torrent of calls and applause went up from the officers. Davis waved them down, took a drink, and cleared his throat.

“Easy, men. Now, as I said, it takes a real captain to resurrect a boat like that, so let’s welcome him in with a song in memory of those who have fallen before us.”

Davis turned to the waifs, who immediately started the introduction to “Dixie’s Land.” Davis stood at the mantel and crooned a few disingenuous notes that turned into a bellow as several whistles went up from the crowd.

Old times they are not forgotten;

Look away! Look away! Look away! Dixie Land.

In Dixie Land where I was born,

Early on one frosty mornin’,

Look away! Look away! Look away! Dixie Land.

Then I wish I was in Dixie, hooray! hooray!

In Dixie Land I’ll take my stand

To live and die in Dixie,

Away, away, away down south in Dixie.

Stepping away from the mantel, Davis raised his glass and waved his arms, and the fiddler joined in as Allice and Cephus stood, both chiming in for the second chorus. Phobetor and the rest of the officers stood forward, lifted their drinks, and joined in for another chorus. The song finished in a clamor of laughter and the ring of brandy glasses clattering against one another. Gradually the officers dropped back against the walls. Davis and Allice returned to their seats, leaving only Cephus standing next to the mantel, the bottle of cognac in one hand and his glass in the other. Taking a sip, he rested the bottle on the mantel.

“Gentlemen, officers, and Major Allice.”

A gentle rumble went up from the crowd as Allice smiled and raised his glass toward Cephus.

“Thank you to Colonel Davis for inviting me here tonight. I tink maybe this is de best party I have been to outside of Biloxi for de Mardi Gras. For those of you that have never been der, it is like New Year Eve in de Five Points, except in Biloxi some of the women have teeth — and some of de teeth are in de front. I suppose that it is getting on in de night, and we need to be getting on to de cards. So, gentlemen, remember, vous n’avez pas besoin de services de renseignements pour avoir de la chance, mais vous n’avez pas besoin de chance ont intelligence. You don’t need intelligence to have luck, but you do need luck to have intelligence.”

The crowd howled, and Davis stood.

“Well said, Captain Cephus. Gentlemen, the game tonight is five-card avalanche. You get five from the dealer and can swap four. Aces up, twos down. Nothing is wild down here except the weather, and there’s no hurricane in sight. Now, that’s all it takes to be a winner, and it’s winner takes all. So, without further ado, gentlemen, let’s adjourn to the ballroom.”

He walked over to Cephus and shook his hand, and then he and Allice escorted Cephus toward the hallway. The officers followed, and Phobetor drifted along with them as they made their way down the hall and up the floating spiral staircase to the second-floor ballroom, where they all found seats. One of the waifs followed the soldiers in and seated himself in the corner at the upright piano. Cephus, Allice, and Davis sat together at the center table under the low-hanging crystal chandelier.

Phobetor sat at a table in the corner with several of the junior officers, who appeared to be unaccustomed to the spirits, which were refreshed again as they were seated. He pulled out his tobacco and rolled a cigarette in the palm of his hand. The piano player started up a riverboat trot, and the dealers all took their seats. Showing a fresh deck to the players, the dealers spread out the first hand.

Phobetor wrinkled his nose as he inhaled the smoke from the yellow cigarette and then folded without looking at his cards. The hand played out as the two young soldiers to his right attempted to drunkenly bluff each other. Phobetor downed his brandy and then called for one of the waiters, who immediately skittered over to him.